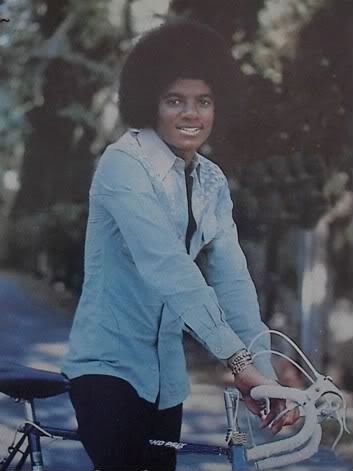

Michael Jackson. (Photo: Courtesy Michael Jackson.)

.

It’s tough to even read the words Aaron Carter typed with a straight face. (If that name means nothing, Carter is the younger brother of Backstreet Boy and erstwhile reality TV star Nick Carter.)

“Remember one very important thing,” Carter tweeted on November 22, in a series of messages the New York Daily News and other outlets are reporting as being since deleted, “Michael passed the torch to me. I never had to ask for him to do that. He compared himself to me.”

.

The “Michael” in question is, of course, the late Michael Jackson—the mere mention of his name, six years after his tragic, sudden death, is enough to stir up a hornet’s nest of emotions.

While few took Carter’s claims seriously—even if Jackson did “pass the torch,” Carter has done a thoroughly miserable job tending to it—there lurks another, more troubling question in the background: Will pop music ever produce another superstar on Jackson’s level?

More broadly: Will the industry ever again have a North Star to guide it?

,

It’s not just Aaron Carter’s delusional Twitter tirades sparking thoughts of how sorely missed Jackson’s talent is in modern pop music, but also Rolling Stonecontributor Steve Knopper’s fascinating new biography, The Genius of Michael Jackson.

,

Will pop music ever again have a North Star to guide it?

,

Knopper spent three years scrupulously reporting on Jackson’s life and work, interviewed more than 450 sources (the book is meticulously indexed and footnoted) and deftly separates fact from myth—Knopper untangles the origins of seminal moments when he can, wryly noting where the legend has overtaken any hope of objective recounting when he cannot.

,

What comes to the fore repeatedly throughout Knopper’s 438-page tome is how singular Jackson’s talent truly was.

.

He’s described as a ceaselessly restless child, one who needed to have someone almost literally hold his head in place to ensure clean vocals, but who would, on a stage before a roaring audience, channel that boundless energy into some of the most dazzling choreography the world had ever seen.

Michael Jackson. (Photo: Courtesy Michael Jackson.)

.

That biological singularity—that even though many of Jackson’s siblings were musically gifted, he stood alone; a supernova distinguishing itself from its surrounding galaxy—is a large part of why Jackson had the impact that he did and continues to have.

.

But the other key ingredient was a willingness to do something new. Knopper writes about how, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Jackson was feeling profoundly confined by the requirements and expectations of continuing to perform with his brothers, when he truly wanted to be doing was digging into the 600-700 songs producer Quincy Jones had amassed to assemble Thriller.

“O.K., guys,” Jones is quoted as saying in Knopper’s recounting, “we’re here to get the kids out of the video arcades and back into the record stores.”

.

Too much of modern pop music fixates on brand maintenance and not enough upon making anything worth listening to.

.

It’s an ambitious mission statement, and, sadly, one that, with a few 21st-century updates, could probably be repeated in control rooms the world over today.

Yet, cowed by the advance of digital technology and a fragmented audience, the music business can only muster hopefuls—these days, far more Aaron Carters than Michael Jacksons are flooding iTunes with music.

.

And while there are isolated instances of an artist cutting broadly across all demographics, captivating fans in staggering numbers—Adele most recently, with Taylor Swift and Beyonce also capable of turning a great many heads at once—pop music circa 2016 is a never-ending cycle of temporary dominance.

Michael Jackson. (Photo: Courtesy Michael Jackson.)

.

An artist breaks through for a moment—remember when Meghan Trainor was inescapable?—and then either flames out (Justin Bieber) or fades away (believe it or not, KT Tunstall once enjoyed heavy rotation on American radio).

.

The sort of long-running, sustainable career Jackson enjoyed, one marked by as much critical acclaim as commercial success, now seems as outdated as a Discman.

Certainly, Michael Jackson had an advantage his admirers and aspirants do not—a firm grip on the monoculture, which dovetailed nicely with the ascent of MTV—but Jackson also, quite simply, wanted it more.

.

Too much of modern pop music fixates on brand maintenance—Katy Perry’s fragrance line or Lady Gaga’s turn on American Horror Story or Nick Jonas’ recurring role on Scream Queens—and not enough upon making anything worth listening to.

.

Michael Jackson’s albums dominated the world and had the added benefit of being full of spectacular musicianship serving songs seemingly carved out of diamonds:Off the Wall, Thriller, Bad, Dangerous—these albums hold up now, decades after their release, not just because Jackson and his collaborators could “see around the corner,” but because they didn’t stop working the songs until they got it just right.

.

In the 1980s, there was the luxury of indulgent major labels—something that, in some cases, can still be found today—but also, the luxury of just having the time.

In the 2010s, artists are constantly under the gun.

Michael Jackson. (Photo: Courtesy Michael Jackson.)

.

There’s scant room for refinement because the 24-hour, non-stop cycle is constantly hungering for something new. (No sooner had Adele released 25 after a four-year absence then music writers pivoted to wondering alou...” single).

.

The unforgiving nature of the business is such that, even if an artist came along possessing even a fraction of Jackson’s talent, it might be smothered before it had a chance to flourish.

Which returns us to the, shall we say, mildly delusional assertions of Aaron Carter. For a moment, let’s give the singer—whose last album, Another Earthquake, was released over a decade ago—the benefit of the doubt.

.

If Jackson “passed the torch” to him, perhaps his role isn’t as a performer, but a proselytizer. Maybe Aaron Carter is meant to help drive attention to pop music’s plight—it’s stale and atomized into a half-billion different audiences.

.

But, if not, then there is one thing upon which we can all safely agree: Aaron Carter, whatever happened, you, sir, are not and will never be the next Michael Jackson.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator will ALWAYS think of

will ALWAYS think of  like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.

like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.