| Author | Message |

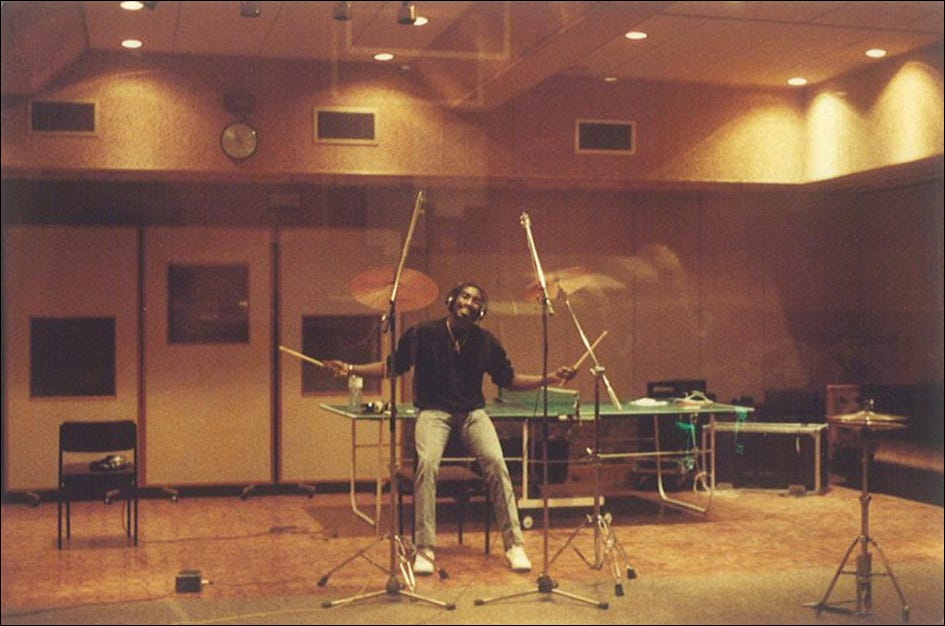

Larry Smith - MUST READ

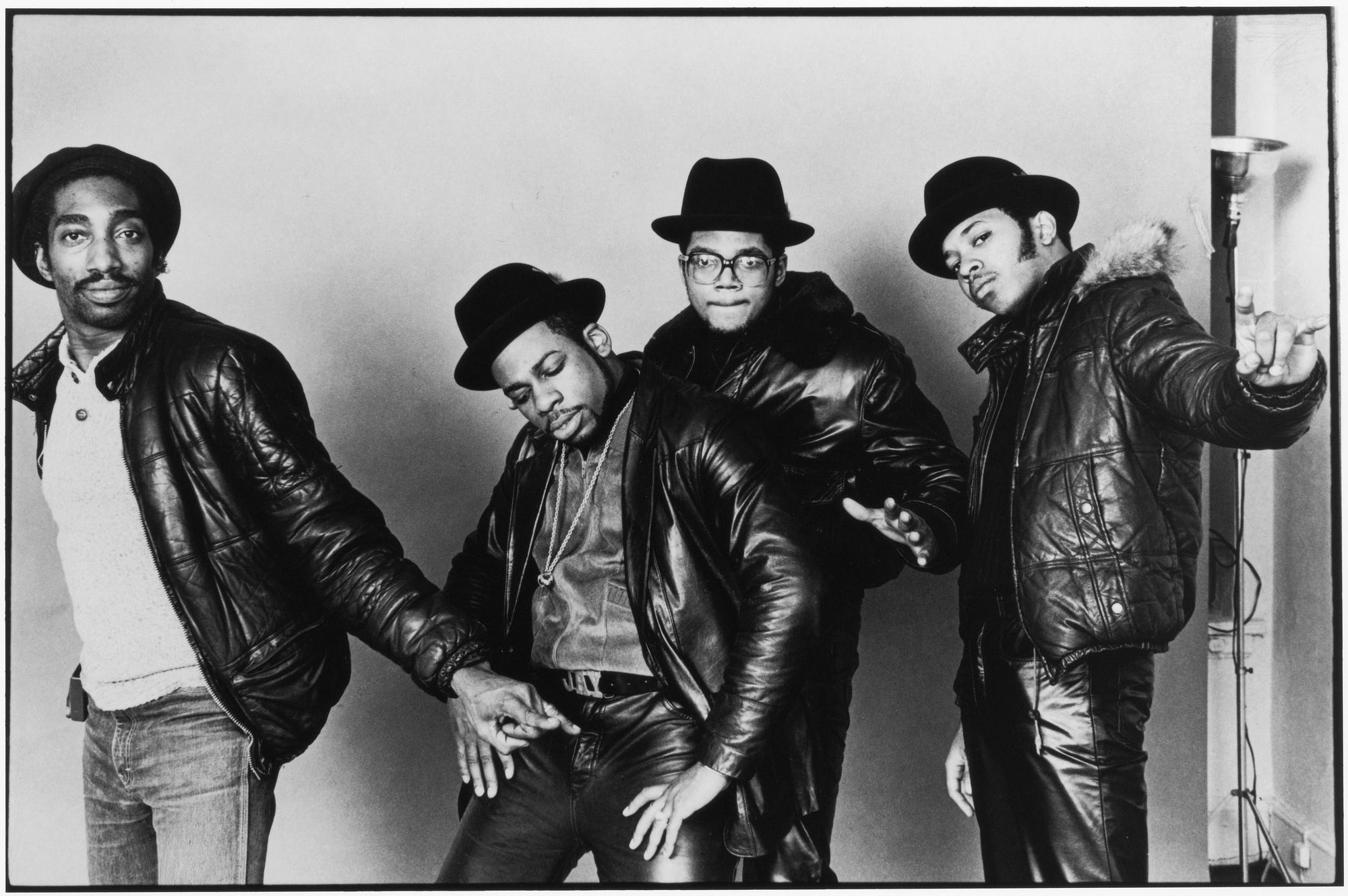

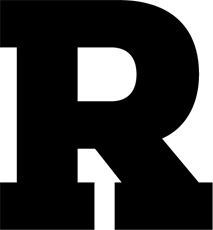

Remember when Run declaredto the world that “Larry put me inside his Cadillac”► on Run-DMC’s breakthrough single “Sucker MCs”? That very same Caddy was featured at the start of the iconic “Rock Box” video, which showed the song’s producer, Larry Smith—along with Run-DMC and their extended entourage—tumbling out of the ride, while guitarist Eddie Martinez worked his axe on the roof. But Larry Smith was much more than the owner of a sweet ride. He’s one of the most important hip-hop producers to ever step into a recording studio, shaping the sound of two of the biggest rap acts on the planet, Run-DMC and Whodini, creating a sonic template that scores of artists would follow. Smith played a major role during the genre’s formative days, crafting hits for Kurtis Blow, the Fat Boys and his own influential group, Orange Krush. While only the most dedicated disciples of the art, such as DJ Premier, actively recognize his legacy (Preem put Larry at the top of his “Top 5 Producers” list in 2009), it was Smith’s unique musical proficiency, combined with his insight into the emerging sounds of the streets, that made him so essential to the development of rap music. While miles of prose has been dedicated to the partnership of Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin, not nearly enough has been written about Mr. Smith, who was Russell’s original business partner before leaving the music industry in the early 90s. Sadly, Larry has been isolated from the public since suffering a serious stroke in 2007, leaving him partially paralyzed and unable to speak. But thanks to the generosity of his old friend Spyder-D, I was granted access to Larry’s final recorded interview so that we might learn a little more about the man behind the music. “He was a perfectionist, he was very creative,” enthuses Smith’s old friend and engineer, Akili Walker. “He could hear all kinds of melodies and was way ahead of his time. He was driven and very generous. There was one time when I was on the road and blowing a little money, and he had went to my house and gave my wife $200 and said, ‘I’m sorry Akili’s blowing his money on the road, take this.’” As a producer, Larry ignored the trends of the day—replaying simple TV jingles—and crafted his compositions around strong basslines, dominant drum tracks and sprinklings of melody, drawing on his years as a musician to create a “future shock” sound that took hip-hop from an underground subculture to a worldwide sensation. 1983’s “Sucker MC’s” marked the end of “old school” rap, introducing a trio from Hollis, Queens who would dominate the hip-hop world for the next four years, becoming the genre’s first international superstars. Following quick on the heels of Run-DMC’s success, the hits Larry created for Whodini—including “Friends,” “Freaks Come Out At Night” and “Five Minutes of Funk”—became certified classics of the genre, and have been sampled by everyone from Nas and Tupac to Dr. Dre and DJ Premier. “Larry Smith is the king of that big beat sound,” explains Stetsasonic drummer Bobby Simmons, who worked with Smith on Whodini’s 1991 Bag-A-Trix album. “Every Kurtis Blow and Whodini record he did? Heavy snare and kick. One thing that I learned from Larry is he’s great with melodies and basslines. I wish I was in the studio when they did ‘Rock Box’ and ‘King of Rock,’ that was a pivotal moment for hip-hop.”   Lawrence Michael “Larry” Smithwas born in St. Albans, Queens, New York in 1951. He was primarily a bass player, plying his trade on the road in the early 70s, following in the footsteps of his musical inspirations. “My heroes were on the road,” explains Larry. “They’d be in Vegas, they’d be in California, they’d be in Europe, in France. My main inspiration was a group called Willie Tee & The Magnificents. When I went around the world, that was my education.” While attending Andrew Jackson high school, a teenage Smith would head down to Clark’s Deli on Francis Lewis Boulevard and 116th Avenue in Queens to practice playing bass, sitting on an ice-cream box when he didn’t have class. “1970 is when I left high school and went on the road,” Smith continues. “I was playing with Jerry Washington, who played juke joints down South. I wanted to play the lead, and where you learn your craft is on the road, so I went down South. I told my mother I was going away for the weekend and I ain’t come back for six months! In 1972 I had just bought a brand new car and within a month I lived in Chicago, until ‘74. After that I moved to playing in hotel bands.” By 1979, former Billboard magazine writer Robert Ford (an old high school friend of Larry’s) had joined forces with fellow music journalist J.B. Moore with the idea of creating a Christmas record for a rapper by the name of Kurtis Blow. Moore penned the lyrics and Ford reached out to Smith for assistance in creating the groove. “I was up in Toronto, Canada, doing a play called Indigo,” says Larry. “He said, ‘I need you to come home for a second.’ I called Denzil Miller, keyboard player extraordinaire who plays everything from classical to jazz. We all got together and we came up with ‘Christmas Rappin.’ The biggest record was [Chic’s] ‘Good Times,’ and Sugarhill had just done their version [‘Rapper’s Delight’]. You look at what’s out there and say, ‘What can we do?’ We changed the cadence up [of the ‘Good Times’ bassline] and just lay in the cut. People only hear two things—they hear the drums and they hear the voice. Every other thing is complementary.” Bolstered by the success of the song and its catchy follow-up “The Breaks,” Larry continued to provide instrumentation and production for Blow’s first three albums. “Larry and Kurtis Blow had the idea of having a band go out and perform with Kurtis, called Orange Krush,” recalls Akili Walker. “They were the first hip-hop band to back-up a rapper. Larry played bass, Davy DMX was on guitar, Trevor Gale was on drums, Bobby Gas on guitar, Rakim’s brother Ron Griffen and Kenny Keys on keyboards and Eddie Colon on percussion. They asked me to be the tour manager and engineer, we toured the country. He used to say, ‘Everytime you mix a show it sounds so crisp and so bright, it’s like we had horns in the band!’—but we didn’t! So whenever we would do a show he would say, ‘It’s time to turn the horns on!’ One day the guys had an idea to go in the studio and record a song,” Akili continues. “That’s when this song ‘Action’ came out with Alyson Williams on lead vocals and Russell Simmons on the ‘Smurf’ voice. It was a local hit, it was very popular, but the drum beat Larry used for ‘Sucker MC’s.’ Larry later programmed the “Action” rhythm into a Oberheim DMX drum machine and dubbed it the “Krush Groove,” utilising it for a quartet of superb Run-DMC songs—“Sucker MC’s,” “Hollis Crew,” “Darryl and Joe” and “Together Forever.” In conjunction with Kurtis Blow, Larry also worked on the Fat Boys’ “Jail House Rap,” Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde’s “Fast Life” and even Rodney Dangerfield’s novelty single “Rappin’ Rodney.” “That’s how I got versed in hip-hop,” enthuses Smith. “It’s not going to the tourist spots, it’s dealing with the people and where they live at. “When I make records, I wanna make the records that people play at 5 o’clock in the morning, without being annoying,” Smith says. “They can be out at 8 o’clock and they tore up and drunk, and yet your record comes on and they’re happy.” After meeting Blow’s manager Russell Simmons for the first time at the original recording session—despite the fact that they’d grown up not ten blocks from each other—Smith and Simmons formed Rush-Groove Productions, producing “The Bubble Bunch” and “Money (Dollar Bill Y’All)” for Jimmy Spicer and “You’ve Gotta Believe” for “Love Bug” Starski. Larry was also introduced to Russell’s younger brother Joseph Simmons. “I took Joe on the road with Kurtis Blow, and the reason that they call him DJ Run is cos he was a helluva DJ.” By 1983, Joe, Darryl McDaniels and their new friend Jason Mizell were ready to record their first demo as a group. “‘Jam Master’ was Joe’s name,” explains Smith. “When they made the record he named Jay ‘Jam Master Jay’ and called D ‘DMC.’ A lotta people don’t know that.” Spyder-D recalls his first introduction to Smith in the winter of 1983: “Russell Simmons put me in touch with Larry, who was living in South Ozone, Queens, near Lincoln Park. So I’m like, ‘I’ve gotta go over there to the south side? Let me bring my pistol just in case!’” “I was a transplant there, cos I’m from St. Albans,” adds Larry. “All you wanted to do was live peaceful and make good music. Because you ain’t from that area, ‘Guess what!? Oh, my man, he got red sneakers on! Let’s whoop his ass!’” “I didn’t have no pistol, I’mma be real,” laughs Spyder. “I did have a knife on me though! Upon my arrival, Larry plays me the 8-track demo he did for Run-DMC, “Sucker MCs” was that demo. They were pondering whether to accept Profile Records offer of $1,500.” “That was a 4-track,” corrects Smith. “I started off going from cassette to cassette, back to another cassette. Everybody was on their job. The reason ‘Sucker MC’s’ sounds like it does—after I put whatever touches I got together—Russell was on top of the lyric, ‘You gotta say it like this, otherwise it don’t mean nothin’. It’s gotta mean something!’ Russell was the businessman of our situation, all I cared about was making music. I made tailor-made music to whatever I was trying to do. I was trying to make ‘Planet Rock’ and my interpretation of it happened to be ‘It’s Like That.’” Russell and Larry introduced a stripped-down sound by necessity rather than design. “‘Sucker MCs’ was just them and a drum machine,” Smith toldBrian Coleman in 2006. “If I had had the budget, I would have hired live performers on the whole first Run-DMC album. But we didn’t have the money. Russell and I took our money and made those early records any way we could.” “We opened up at some bourgeois, upscale supper club in Manhattan,” explains Spyder. “The crowd truly wasn’t hip-hop. Run and them performed ‘It’s Like That’ and they were like stiff wooden puppets. They standing there with the plaid jackets and the Pumas on. One of D’s lenses popped-out, and he didn’t even pick it up! It was a disaster. Then we got in Larry’s Cadillac, Larry was flippin’ on them in the ride! ‘Yo! Y’all was fuckin’ wack! If you’re wack at The Fever, you’re gonna get shot! Them boys New Edition was wack two weeks ago, niggas started shootin’!” At this point, The Fever was the center of the rap universe. “We’d be at The Fever with Kurtis Blow and myself over in one corner,” reminisces Larry. “Grandmaster Flash over here, we got Spoonie comin’ through every now and then. And the funny thing about it, we all got along! Grandmaster Caz, all in the same spot! We might say we don’t like them, but guess what? Under the darkness of a club we got along. We laughed, we joked. You’ve got to look at everybody as being valuable, no matter what. Even the worst guys—we look at them and learn what not to make!”  Perhaps the most significantcontribution that Larry Smith made to the emerging Run-DMC sound was the introduction of live electric guitars to rap, often attributed to Rubin. “We were at Greene Street,” remembers Spyder-D. “It was he that melded rock and hip-hop when he did ‘Rock Box.’ He brought out his bass and started cranking that hellacious bassline that became the backbone of that groundbreaker.” “That’s part of my musical background,” continues Smith. “Because I played in rock ‘n’ roll bands. I was down with the speed metal—hard and dirty—that’s where that came from.” “Rock Box” made history as the first rap video to play on MTV, immediately exposing the crew to a national audience far beyond the tri-state. “Him and an engineer named Rod Hui from Greene Street were the first to put that reverb effect on the drums on those Run-DMC songs, and it became a signature sound for hip-hop,” notes Akili. “I think Rod Hui got it from the rock ‘n’ roll guys, but he added it to the hip-hop tracks.” Smith’s work with Whodini was equally as groundbeaking and also rooted in his relationship with Simmons. As Ecstasy from Whodini told Jesse Serwer in 2009: “One night [me and Russell] was up in Disco Fever and he suggested to me, ‘maybe you and Larry need to hook up.’ Me and Larry became friends, and when we was going to record again, we said ‘Lar, what you got?’ Went over his house, he laid out his ideas real fast and the first was ‘Five Minutes of Funk.’ We made that in like a half hour. “The technical reason why he went and worked with us is because he was fixing his car with a band member, a bass player, and the fan belt cut off his finger, and he had to pick it up and rush the guy to the hospital,” Ecstasy says. “Larry needed some money to help the guy get his operation real quick, to help the guy save his finger. He said, ‘I’ll go with y’all to London, just give me some money quick.’ He’s a bass player too so he thought, ‘what if that was my finger?’”  Whodini’s second album, Escape, was recorded in London over the space of two weeks in 1984 at Battery Studios. “Jive Records did not want to spend money on studios in the States when they already had this studio in London.” Akili explains. “That was a plus for Larry, because London had technology, recording and instrumentation that was not available in the States yet. He could experiment with these new sounds, that’s why the sound is so great on Whodini’s albums. You could put Larry’s tracks against another song from those days and you could hear the difference—it’s big and clean. Larry’s specialty was the breakdown. He’ll take the instruments out and you’ll just hear drums and bass, or you might hear drums, bass and guitar. I was in awe at how he could do that. Smith also knew the importance of pushing his artists. “[Larry] would tease us about Run and them,” continues Ecstasy. “We were rivals. I think he would do the same thing when he would go back in the studio with them. He would say, ‘That song is alright, but Run and them got a song that will bust your ass.’ Larry is the type of guy who will strip you of all your ego while you’re in the booth, telling you that you ain’t shit, this person’s better. Not to make you mad, or get you frustrated, or make you quit, but to get you to come up with some shit. If you could make him shut the fuck up, you did your job. When we got to the end of song and he couldn’t say nothing, we knew we had some good shit.” Escape went on to make huge stars of Whodini, who followed up with the equally well-received Back In Black the following year. As the Def Jam label began picking up steam, things soured between the two former partners Russell Simmons and Larry Smith as their paths began to diverge. “When they did the deal for Def Jam, I was uptown, dealing with our people and learning my craft, and Russell was downtown,” reasons Smith. “He’d brought Rick Rubin into the picture, and Rick Rubin brought LL, and that was the money. That’s why I got mad at Russell, cos I didn’t think money should be held over loyalty.” According to a 1985 Village Voicepiece by Nelson George, Smith then signed a publishing deal with Jive Records (even though Russell had promised it elsewhere), and accepted the role of music supervisor for the film Rappin, putting him in direct competition with Krush Groove, succeeding in “taking the smile off Russell’s face” in the process.  Towards the end of the 1980s, Larry found himself beginning to tire of the pressures of the industry. “The first Whodini record I did, it took us six weeks to do the album,” says Smith. “One producer, one group. The next one took us nine months. Next one took us a year and a half. You’re looking at four years that transpired, and the more success you got, the more you criticised yourself and you weren’t satisfied.” Larry and Whodini worked together one last time on 1994’s surprise hit “It All Comes Down To The Money” with Terminator X, which was a fitting swan song for everyone involved. As the sampling-based sound of Marley Marl began to dominate late 80s hip-hop, Smith found himself feeling disenfranchised. “I just couldn’t bring myself to sample. I was totally against it.” Larry told Brian Coleman. “As a musician, I just couldn’t use something that I didn’t create myself. The only reason I jumped out the game was because of my ego.” Mr. Smith’s discipline and musical vision have been sorely missed ever since, but his influence is still being felt to this day. While researching this article, I was horrified to discover that this pioneering musician is currently languishing away, virtually forgotten, in a bare-bones nursing home as “a ward of the state of New York,” which means that he isn’t able to afford the care and attention he needs during this difficult period.   We hope this story will raise awareness about the plight of an unheralded music legend, at this difficult time for him. We hope to inspire music fans to recognize Larry Smith’s contributions, to honor the man for the enjoyment we’ve received from his work, to celebrate his vision and his passion for the art form. Please stop by the “We Love Larry Smith” Facebook page to pledge your love for the great man—with words, with deeds or with financial support. Let’s send a message to this pioneering artist that his legacy will never been forgotten.

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I was walking down Queen Anne Road in Teaneck NJ must've been Summer of '83 and this dude I kind of knew named Bobby Kennedy was walking down the other side of the street toward me with a huge box that was hanging down by his ankles and he was blasting this song. I just stopped dead in my tracks and stared at the music coming out of the box as he walked by. It was like being beamed into another dimension. It blew my mind completely. Never heard anything like it, nothing even close.

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Good read, thanks hardwork | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable