I recently came across a thesis that examined the relationships between Sir Nose'd D'Voidoffunk, Dr. Funkenstein, and Star Child, on an even deeper level. I had a whole new appreciation for the song, as well as the imagination of George Clinton, after reading this excerpt:

Signifyin(g) on Record

I am Sir Nose'd D'Voidoffunk

I have always been devoid of funk

I shall continue to be devoid of funk

Star Child, [cue horns] you have only won a battle!

I am the subliminal seducer

I will never dance

I shall return, Star Child!

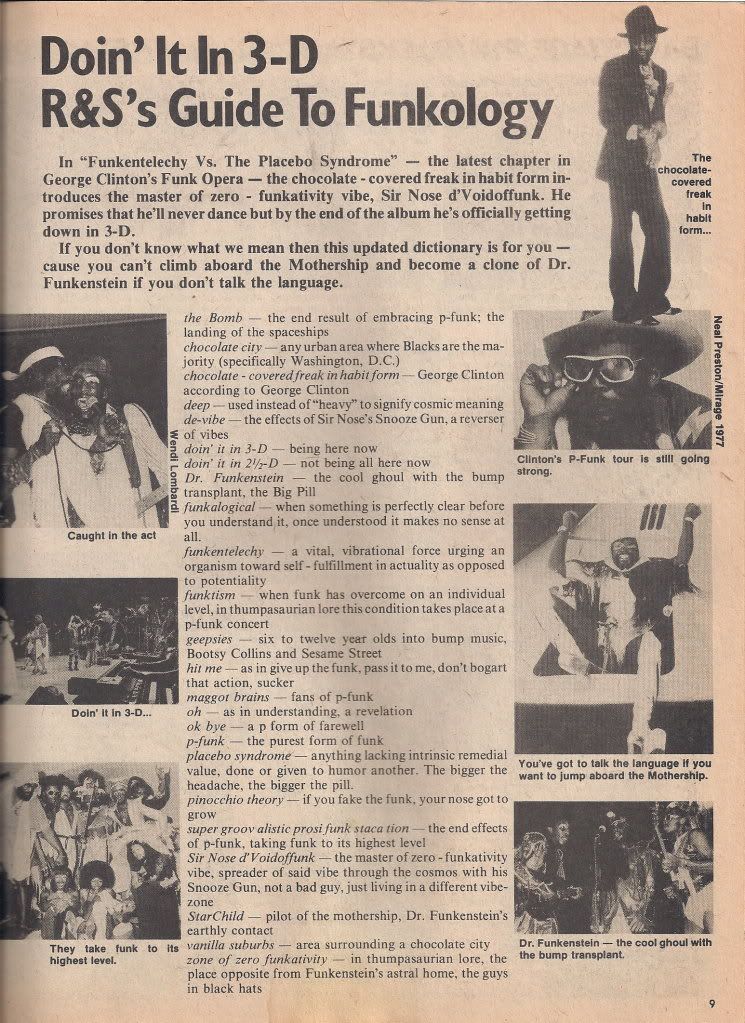

These words open "Sir Nose d'Voidoffunk," track 2 of Parliament's 1977 album Funkentelechy Vs. The Placebo Syndrome, part three in the interplanetary saga of Star Child, commander of the Mothership and paragon of all things funky. Our hero at last has a nemesis. Sir Nose, as his name suggests, is entirely "devoid of funk;" the maker of the "Placebo Syndrome" -- a plague that induces passive mass consumption-- he seeks to rid the universe of the unruly Star Child and his gospel of freedom through funk. Yet Star Child gleefully intrudes with an eerily familiar horn figure that enters immediately after the mention of his name. Drums, synthesizer, bass, guitars and a chanting choir enter successively, and before Sir Nose can finish, the band drowns him out entirely. Our hero has strength in numbers. Entering with a rap at 1:20, Star Child seems utterly unfazed by Sir Nose's threats.

Both Star Child and Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk are portrayed on record by George Clinton. While the Star Child persona is represented by Clinton's "natural" speaking voice, the "Sir Nose" voice is distinguished by tape manipulation and a grotesque panoply of studio effects. Rudely interrupting Sir Nose's monologue, the horn figure which signals Star Child's presence is a lift from "Merrily We Roll Along," best known to most Americans as the theme for Warner Brothers' Merrie Melodies cartoons. As the track progresses, the horn figure returns at odd intervals amidst verbal allusions to children's nursery rhymes and television advertisements, layers of synthesizers, and still more layers of electronically altered voices. Clinton's recorded oeuvre is rife with such collusions of technology and allusion. The Signifying Monkey tales cited by Gates in his work of the same name turn upon the Monkey's proclivity for stirring up trouble through the use of figurative language. Typically, the Monkey starts a conflict by repeating an insult which supposedly originated from the Elephant to his friend the Lion; offended, the Lion resolves to fight the Elephant, who easily beats him. Eager to deflate the Lion's self-proclaimed status as "King of the Jungle," the Monkey repeatedly tricks Lion into fighting Elephant, the true "King of the Jungle," through virtuosic wordplay. Unable to see through the Monkey's lies or, more importantly, to perceive the difference between literal and figurative language, the Lion is fooled time and time again. The Monkey, then, is the prototypical trickster figure: an inveterate mischief-maker who, through rhetorical play, is able to thwart his physical betters. As Ayanna Smith writes, "It is superiority in wit that allows the trickster to gain the upper hand."

A modern-day trickster, Clinton's Star Child shares the Monkey's propensity for oblique insults, rhetorical indirection and intertextual punning. The following example, from "Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk," is typical:

Has anybody seen ol' Smell-o-vision?

Where is Sir Nose'd?

If y'all see Sir Nose

Tell him Star Child said:

"Ho! Put that snoot to use you mother!

'Cause you will dance, sucker!"

Note that Clinton/Star Child never addresses Sir Nose directly; even though Sir Nose may be well within earshot, Star Child's taunts are (loudly) addressed to a third party. Gates calls this form of rhetorical indirection "loud-talking" and identifies it as a common "mode of Signifyin(g)."Star Child also draws attention to his enemy's most prominent physical feature through a remarkable pun that conflates two senses; if "Sir Nose" is so named to recall the perception that white people and self-loathing black "sellouts" talk through their noses, Star Child suggests here that his doubly unfunky nemesis actually sees through his nose as well. Star Child/Clinton also draws an implicit parallel between the ersatz cool of Sir Nose and the crass insincerity of television and evokes a recent P-Funk maxim: "If you fake the funk, your nose will grow." Finally, Star Child offers his retort to the obstinate Sir Nose's song-opening monologue, promising to make the "sucker" dance. Like the Signifying Monkey rapping to the Lion, Star Child caps off a series of playful insults with a direct threat.

Musical Signifyin(g)

On Parliament's "Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk," individual musical and lyrical references are explicit (i.e., they are meant to be recognized by the listener) and often pointedly disjunctive, providing a level of narrative commentary but remaining as textual fragments. In fact, the relatively unharmonious juxtaposition of borrowed texts -- the nursery rhymes "Three Blind Mice" and "Baa Baa Black Sheep" and the composition "Merrily We Roll Along" -- serves first to emphasize the received social and cultural meanings of each. Only upon repeated listens do the group's textual alterations become fully apparent. With each alteration -- each "repetition with a difference" -- Clinton signifies, producing new meanings from old texts. The lyrics of "Three Blind Mice" are quoted almost verbatim, though they are sung to a different melody and a markedly syncopated rhythm. "Baa Baa Black Sheep," chanted rather than sung, is perverted through a drug reference ("Baa baa black sheep have you any wool?/Yes sir, yes sir, a nickel bag full"). The group's usage of "Merrily We Roll Along," the theme of the Warner Brothers cartoon series Merrie Melodies, is perhaps subtler.

Clinton doesn't so much upend the "Looney Tunes" theme as adapt it to his own uses; the meaning of the original theme is not subverted but is instead compounded and expanded upon through its employment in a new context. The opening melody line of "Merrily We Roll Along" is redeployed throughout "Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk" in snippets, entering at unexpected times and often clashing tonally with the rest of the track. The rhythm of the theme itself is unchanged, but through each iteration it is subtly reharmonized, at times pointedly discordant and at other times, relatively harmonious both internally and in relation to the other instruments. The theme is never fully assimilated to the surrounding tonal and rhythmic material; it is always somehow at odds with the basic groove. The theme first appears immediately after the unaccompanied Sir Nose first mentions Star Child, thereby operating as an aural sign for the latter character; it is also the first tonal material introduced in the song. Consisting of a trumpet , a saxophone and a trombone, the horn section enters and exits with the first few notes of the theme in under two seconds (from approximately 0:18 to 0:20), following with a three-note fillip. All three instruments play variations of the melody at dissonant intervals from each other.

The near-simultaneous entry of drums and the horn theme acts as a sharp, wicked retort to Sir Nose's preceding declaration: "I will never dance!" Together, the steady, "on-the-one" drum pulse and the frantic horn figure encapsulate the song's meld of groove and cacophony; the irritatingly sharp trombone provides an unruly edge to Star Child's already impolitic interruption. With the eighth-note pulse of the high hat in place Sir Nose's cries spiral upward in pitch (more studio trickery) and downward in volume (ditto) while Worrell teases atonal squelches from a Moog synthesizer. Sir Nose continues to protest that he will never dance, but his cries grow weaker as bass and guitar enter with the main groove at the 55 second mark.

Above this groove, which will underlie every subsequent iteration of the "Looney Tunes" theme, a choir chants: "Syndrome, twiddly dee dum. Humdrum, don't succumb." Music and words serve as another firm rebuke to the weakening Sir Nose, whose unfunky placebo is no match for the insistent rhythmic force of Star Child and the clones of Dr. Funkenstein. The groove which is established at 0:55 (and fleshed out with the entrance of piano and the full backbeat at 1:17) -- what I will call Groove 1-- is characterized by the "more or less swung sixteenth notes" which funk scholar Anne Danielsen writes "are almost always present in a funk groove." The "One" – the heavy downbeat -- which Clinton invests with near-mythic significance (cf. such song titles as "Everything is On the One") is conspicuously absent from the bass-and-guitar riff itself. Here, the "One" is instead provided by a cymbal crash of the drums – otherwise playing a slowed-down variation of the standard disco rhythm (bass drum on beats 1 and 3; snare on beats 2 and 4; high hat on straight eighths, dropping the "on" beats on some measures) -- on every other downbeat. As on many other P-Funk songs, time almost seems to stop just before each iteration of the One; here, however, the first two notes of Groove 1 fill in the space just before the One, threatening the absolute dominance of the downbeat.

Over Groove 1 (with bass, guitar, drums, piano and Worrell's synthesizer ornamentations), Star Child and a choir begin to sketch out a context for the Looney Tunes quote. Between 1:46 and 2:10, the choir sings the familiar children's song "Three Blind Mice" to a new tune while Star Child offers playful commentary (with Star Child's comments in parentheses):

Three blind mice (let me put on my sunglasses)

See how they run (so I can see what they ain't lookin' at)

They all ran after the farmer's wife

Turned on the fun with the water pipe

Have you ever seen such a sight in your life? (ho!)

Those three blind mice (yeah)

Those blind three mice

"I love those meeces to pieces," Star Child/Clinton finally says of the titular mice, repeating and revising a catchphrase from the Hanna-Barbera cartoon Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks. Unlike cartoon cat Mr. Jinks, who would say, "I hate those meeces to pieces," inveterate mischief-maker Star Child identifies with the mice of the cartoon (and those of the song). Like the Signifying Monkey, both Star Child and the mice delight in stirring up trouble and outwitting their oppressors. Explicitly referencing and implicitly identifying with cartoon characters that would likely have been familiar to P-Funk's late-1970's audiences, Clinton makes plain the purpose of the Merrie Melodies lift: Bugs Bunny (himself an update of 19th century trickster Bre'r Rabbit), Tweety Bird, Pixie and Dixie and other cartoon characters all thwart their antagonists through wit rather than brute force, making fools of their oppressors in the process. The cartoon theme, then, is a symbol of modern-day tricksterism, the aural signature of a hero who sows creative chaos behind the backs of his joyless oppressors.

With a few small interpretive leaps and the appropriate store of pop-culture knowledge, anyone parsing the lyrics of "Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk" might find the same parallels I have suggested. While the signification of each musical and lyrical quotation depends on an awareness of its original context, Star Child/George Clinton offers interpretive clues -- and additional layers of allusion -- through his own spoken asides. Agawu writes in Music as Discourse that "music cannot interpret itself;" only through an external verbal supplement can its meaning or "truth content" be divined. On Parliament and Funkadelic's recordings, narrator Clinton provides that supplement. Like the sacred texts of the Yoruba, P-Funk songs contain their own "discursive metalanguage." Star Child's interpretations (like Esu-Elegbara's) are presented as riddles, leaving additional interpretive work to the listener. The significance of the Merrie Melodies lift on "Sir Nose D'Voidoffunk" emerges only through layers of textual signification and allusion.

Further reading:

P-Funk on Record and Onstage

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator New topic

New topic Printable

Printable