By: Michael D. McClellan | Ingrid Chavez vanished into rumor in the 1990s, disappearing before our very eyes, her story climaxing with a high-profile Prince collaboration and...

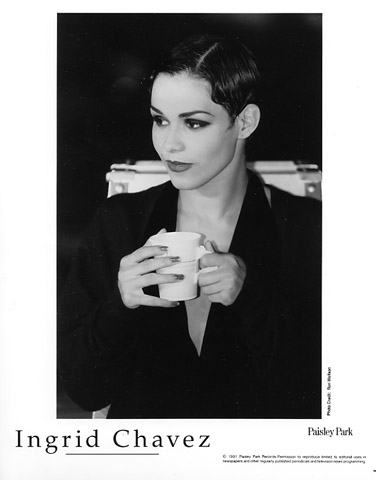

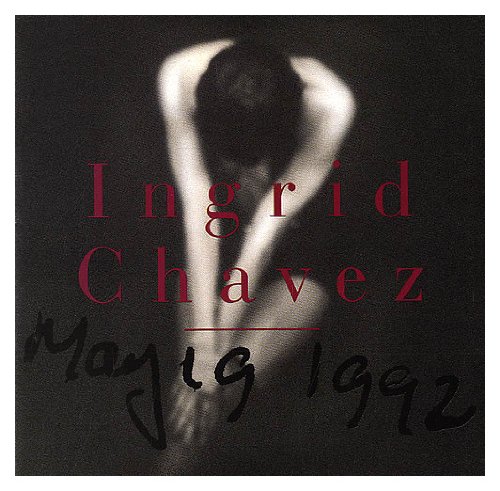

Chavez released her debut solo album, May 19, 1992, on Prince’s Paisley Park Records, and then disappeared into the ether. The pop music landscape, as fickle as ever, simply rolled on: Prince changed his name to a symbol, Madonna kept pushing buttons, and a new wave of hip-hop artists started dominating the charts, Eminem, Dr. Dre, and Jay-Z among them. Meanwhile, Chavez retreated into relative obscurity, getting married, starting a family, and living vicariously through her husband’s work, English singer-songwriter David Sylvian. She was forgotten about almost as quickly as she’d come.

...

Clearly, Ingrid Chavez loved making motherhood her main gig, and while the urge to make music may have been repressed by the desire to be there for her children, it’s hard to imagine that urge ever really going away. We’re talking about the same Ingrid Chavez who arrived at Paisley Park during one of the darkest, angriest periods in Prince’s life, her positivity prompting him to table The Black Album and embrace a new spiritual awakening.

“I’m happy to be back,” Chavez says, smiling. “Songwriting is something that I enjoy a great deal. I didn’t realize how much I missed it until I started doing it again, and it brought back so many memories of my time together with Prince. We hung out together, played pool, talked about everything from sex to God, and worked on our records together.”

The chain reaction that produced Lovesexy starts with a robbery.

...

“Steve Snow was a musician and my boyfriend at the time,” Chavez says. “We had formed a band called China Dance, and the candy factory was the perfect place for us to rehearse – until one day we drove a friend of ours to the airport and returned to find all of our equipment was gone. The thought of someone breaking in and stealing our stuff was so scary. We were really young, and I’d just given birth to my son Tinondre. Steve and I just looked at each other and said, ‘What are we going to do?’ I was afraid to stay in the warehouse after that, because it was in a really bad part of Atlanta. Someone had just burglarized our place and all I could think was that it would happen again, so we went and stayed with a friend.”

Snow, who was from Minneapolis, had a straightforward idea: Save up enough money for plane tickets and move back to his hometown.

“I didn’t have a compelling reason to stay in Atlanta,” says Chavez, who was born near Albuquerque and sent by her mother to live with family in Georgia when she was 10. “I wasn’t leaving anyone behind that I was going to miss terribly, so moving to Minneapolis was like an exciting journey to somewhere new. It was scary when we first got there, because we moved in with Steve’s uncle on the north side of Minneapolis, which was totally gang infested at the time. You would hear gunshots in the night. We were finally able to rent an apartment and start our new life there.”

“Before I met Steve, I was listening to Prince, The Time, a lot of music like that.

...

Chavez and Snow slowly grew apart, breaking up after that first year together in Minneapolis and triggering the next step in that Lovesexy chain reaction.

“Artistically, Steve and I did find some common ground,” she says, “but I think there were times when we didn’t share the same creative vision. The ride got a little bumpy.”

Although her relationship with Snow had soured, Chavez kept writing poetry and staying connected to the Minneapolis music scene. She also worked part-time in a coffee shop to pay the bills. It was a gritty, uncertain period in her life, and someone with less moxie might have packed up and moved on. Not Chavez. She didn’t have much, but she had confidence in her talent and a belief that a higher power was at work in her life.

By the time Prince released 1987’s Sign O’ the Times, he was one of the biggest-selling artists in the world, his reputation growing in lockstep with his popularity, from his debut album For You to his mainstream breakthrough 1999 to the global smash Purple Rain. To say that Michael Jackson owned 1980s pop music would be only partly true. Jackson dominated the charts, but Prince was right there with him, matching MJ hit-for-hit, stadium-for-stadium, heart-for-heart. Artistically, their work couldn’t have been more different. Sign O’ the Times was as eclectic as Jackson’s Bad was polished, which cut to the very core of the artists themselves: Jackson made music that appealed to everyone, chained to formula, with an insatiable need to feel loved. Prince made whatever the hell he wanted, without constraint, which freed him to create brilliant music.

“Prince was always pushing himself artistically, and always challenging those around him,” says Chavez of his music-making. “The first time I saw Prince was at the club First Avenue. We passed each other and made eye contact, but on that night we didn’t speak. When I finally met Prince I was instantly comfortable around him. He had this ability to see creative potential in a person before they saw it in themselves.”

On September 11, 1987, Paisley Park officially opened. Prince was between albums, with Sign O’ the Times winding down and something called The Funk Bible in the works. He had also released the Sign O’ the Times concert movie, which was praised critically and attended en masse by the most hardcore Prince fans. The movie, with live clips re-shot at Paisley Park, was a svelte jolt of everything that captured Prince at his most dazzling: The singing, the dancing, the multi-instrumental talent, the rapport with his band, and those bolero-chic outfits that only The Purple One could carry off.

There was something else about Prince that stood out during this era; his music had taken on a decidedly darker edge, matching his mood. On Cindy C., Prince sang about feeling rejected by a high-class model in Paris. Rockhard in a Funky Place was about a guy on the prowl for sex in a whorehouse. Superfunkycalifragisexy urged people to drink blood and dance. All of these tracks were being readied for inclusion in the 1988 release of The Funk Bible, an album that Prince insisted be produced without printed title, artist name, liner notes, production credits, or photography. Everybody – family, friends, employees, musicians – was on edge around Paisley Park. Prince ratcheted up the tension at every turn, demanding more from everyone and pressing forward with a project that was certain to alienate segments of his fan base. Warner Bros, meanwhile, continued to publicly support The Funk Bible, prepping 400,000 copies for distribution while privately bracing for a commercial failure. Looking back, it’s hard to imagine a more toxic time than those early days at Paisley Park.

All of that changed on a bitter cold December night, when Prince ventured into a Minneapolis bar with his entourage. Chavez was also there. She wasn’t supposed to be – if not for a friend’s incessant coaxing, she would have spent the evening at home, comfortably out of the weather. But fate has a funny way of working. Turns out, her decision to go out that night was the final reaction in Lovesexy’s self-amplifying chain of events.

“I wasn’t going to go to the bar,” Chavez says. “Prince strolled in soon after I got there, and he kept staring at me. I thought he looked very puzzled, and I was very curious as to why I would puzzle him. So I sent him a note. It read, ‘Hi, remember me? Probably not, but that’s okay, because we’ve never met. Smile…I love it when you smile.’ I didn’t sign it or anything. I just gave it to Gilbert Davison, who was Prince’s manager at the time, and who was with him that night. Prince took the note and read it, and then he had Gilbert come and get me. So I walked over and sat with him.”

The connection between poet and recluse was immediate.

“This was during the Sign O’ the Times period, when he used to wear those mirror heart bracelets. He took the one that he had on his wrist and put it on my wrist. It was so surreal. It felt like a strange dream that couldn’t possibly be true; one minute I’m sitting at home alone, the next I’m sitting in a bar with Prince, one of the most famous singers in the world, and I’m wearing his mirror heart bracelet on my wrist.”

Long known for his playful side, Prince quickly warmed to what came next.

“We started talking, and he asked my name because I hadn’t signed my note,” Chavez says. “I introduced myself as Gertrude and he immediately said that he was Dexter [laughs]. From that moment on, that’s who we were to each other. When I look back on some of my journal writing from that period, I never referred to him as Prince. I referred to him as Dexter in all of the passages.”

As they talked, Chavez had no idea of the inner struggle taking place within her new friend. Warner had grudgingly started sending out advance copies of The Funk Album to dance club deejays in England, with mixed results. Prince’s latest movie project, Graffiti Bridge, had hit some speed bumps and was on temporary hiatus. A new form of music – rap – was starting to gain mainstream popularity, and yet Prince had responded with Dead on It, in which he trashed the new art from and incorrectly predicted its demise.

Little could anyone have known that everything would change the night Prince met Ingrid Chavez.

“Prince asked me if I wanted to take a drive,” she says. “I sat in the front seat next to Gilbert, and he sat in the backseat. It was nighttime. Prince had Gilbert put the mirror down so that we could see each other’s eyes. The next thing you know, we’re on our way to Paisley Park.”

“He put me in a room and told me that he’d be back,” she says, “and then he disappeared. I was just hanging by myself for what seemed like an eternity. I was left with time on my hands, and I didn’t have anyone in the room with me, so I just did what I do whenever I’m alone, which is write. He came back eventually [laughs].”

What happened next remains shrouded in mystery and baked into legend, but the end result would prove to be a crossroads moment in Prince’s personal and professional life. The story goes something like this: Prince calls Susan Rogers, who was working as his sound engineer at the time, and asks her to come to Paisley Park. Rogers shows up to find Chavez alone, in a candlelit rehearsal room. Prince joins them a short time later, and after a brief conversation, Rogers decides to leave. In the hours that follow, legend has it that Prince experiences an awakening and sees God – not in physical form, but in everything around him. The legend continues that Prince now sees The Funk Bible for what it is – an evil force full of rage, the lyrics poisoned with guns and violence – and that a voice tells him not to release the record.

This much we know to be true: Prince moved quickly to convince Warner Bros. to scrap the project. The company agreed to destroy all of its copies of The Funk Bible, which would famously come to be known by another name: The Black Album.

“Prince did tell her that she had to meet me,” Chavez says, conceding part of the story. “She came to Paisley Park later that night, and Prince and I talked about a lot of things after she left. He did end up cancelling The Black Album, but I didn’t know anything about that record at the time. All I knew was that it got cancelled.”

Whatever happened, Prince emerged from the experience a changed man. Gone was the moody artist prone to tempestuous outbursts. In his place was an enlightened, spiritual being whose approach to songwriting would be forever altered.

And whether she knew it then or not, Ingrid Chavez’s own world was about to tilt dramatically on its musical axis.

pt 1

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-2418147-1326286221.jpeg.jpg)