| Author | Message |

Question for guitar geeks Hey guys,

I'm hoping one of you will be able to help me with the following. Sometime in the early 90's Prince did an interview for a now-defunct guitar magazine. I think it was "Guitar World" if I'm not mistaken. It included an article, a description of his rig and also some tablature. I'd love it if anyone has any scans if they could post them (I'm primarily interested in the tabs). Speaking of which, does anyone have any good sites for Prince guitar tab? Relatively speaking, it doesn't seem like there are many good Prince tabs out there. Thanks in advance. Mahalo. [Edited 8/3/09 9:11am] Ur always on my mind...DAY AND NIGHT, BABY ALL THE TIME...U mean so much 2 me...A LOVE LIKE OURS... just had 2 be | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

horseluvaphat said: Hey guys,

I'm hoping one of you will be able to help me with the following. Sometime in the early 90's Prince did an interview for a now-defunct guitar magazine. I think it was "Guitar World" if I'm not mistaken. It included an article, a description of his rig and also some tablature. I'd love it if anyone has any scans if they could post them (I'm primarily interested in the tabs). Speaking of which, does anyone have any good sites for Prince guitar tab? Relatively speaking, it doesn't seem like there are many good Prince tabs out there. Thanks in advance. Mahalo. [Edited 8/3/09 9:11am] I have Guitar World from '94 with "Symbol" on the cover, there are the articles about Prince and very short interview, but nothing about his rig I think..tabs are just excerpts (e.g. Let's Go Crazy riff, 1999 funky riff), nothing special..I could post you the scans tomorrow. Only good page with tabs is www.ultimate-guitar.com, BUT Prince's tabs are not very accurate [Edited 8/3/09 9:28am] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

sites-im not sure-i usually try and work em' out myself-but..

the very best Prince tab book is Purple Rain -off the record-every track fully tabbed for guitar the lets go crazy solo.....the whole PR solo.....yummy i adore that book and have programmed becking tracks for a few tracks note for note on all instruments-and man they sound amazing | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

The scans are on the Prince tabs and chords forum...It hard to see but

it's there....I love that forum..... | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I need the taab for the PR solo...can't find it...Trying to work it out

but....you know... | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

nyse said: I need the taab for the PR solo...can't find it...Trying to work it out

but....you know... There's very good one on the www.ultimate-guitar.com, it's the Guitar Pro version (don't remember which one, try them all - it's the one with all arrangements) | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

thanks zaza! ! ! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

nyse said: thanks zaza! ! !

You're welcome | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

^^

Thanks again...I'm going to sign out.. cause I'll be bizzy with this for the next few hours | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

[/quote]

I have Guitar World from '94 with "Symbol" on the cover, there are the articles about Prince and very short interview, but nothing about his rig I think..tabs are just excerpts (e.g. Let's Go Crazy riff, 1999 funky riff), nothing special..I could post you the scans tomorrow. Only good page with tabs is www.ultimate-guitar.com, BUT Prince's tabs are not very accurate [Edited 8/3/09 9:28am] [/quote] Zaza - if you could post those scans - I would be very grateful Ur always on my mind...DAY AND NIGHT, BABY ALL THE TIME...U mean so much 2 me...A LOVE LIKE OURS... just had 2 be | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

horseluvaphat said: zaza said: I have Guitar World from '94 with "Symbol" on the cover, there are the articles about Prince and very short interview, but nothing about his rig I think..tabs are just excerpts (e.g. Let's Go Crazy riff, 1999 funky riff), nothing special..I could post you the scans tomorrow. Only good page with tabs is www.ultimate-guitar.com, BUT Prince's tabs are not very accurate [Edited 8/3/09 9:28am] Zaza - if you could post those scans - I would be very grateful I will send you an orgnote tomorrow [Edited 8/3/09 12:55pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

lol

there is a used copy of the off the record book on Amazon for £95!!!!! wow-i like Prince but..... | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

October 1998

THE ARTIST Representatives of the Artist arrange for a meeting -- a secret rendezvous -- between myself and the gifted one at The Hit Factory in New York City. . . The Artist, a platinum jewel attached to his ear, arrives clad in black and carrying a transparent walking stick with blue sparkling stars. His is everything I could hope for, as gloriously ineffable as his name is unpronounceable. Guitar World: You won't allow your interviews with the press to be tape recorded. Why? Presumably, you'd like to be able to guarantee more accurate representation of our conversation with a recorder. 0{+> : To me, a tape recorder is like having a contract. And I don't want to have a contract with you. I don't want this to be business. I want this to be a normal conversation about something that we're hopefully both passionate about: music. And when there is no tape recorder, our relationship is based on trust. So if you write lies, you're the one betraying that trust, and you'd be the one soaking up all that negative energy. But I trust you, so we don't need a tape recorder. And I can talk now, because I'm free. A lot of my music has to do with being free. I'm not chained anymore. And being married to Mayte has made me feel more comfortable with speaking in public. GW: Earlier this year you released Crystal Ball, a mammoth five-CD set. It contains some incredible outtakes and a number of unreleased tracks, but still no live music. You're hailed as being one of our best live performers. You've been doing incredible shows for years. Why have you avoided releasing live material? 0{+> : I have everything on tape, man, including all the informal jams. I record everything I do, just like Jimi Hendrix did. And eventually a lot of it will be released. To me, Crystal Ball was a test case. I was testing the water to see if people would buy music over the internet, and whether they would be receptive to a five-CD set. Since the album was a success, it leads me to believe that the whole interactive thing offers great possibilities. I mean, why not make a five-CD live album, with people on the internet choosing their favorite tracks? Why not poll the fans on our web site and let them compile it? All this will happen. Soon. For example, I just performed and recorded a 45-minute jam with Larry Graham called "The War," which I edited down to 26 minutes. It's a fantastic track. In the past, my old record company would never allow me to release something like that. Now that I have my own label, I can think about releasing that kind of stuff. GW: What were some of your most memorable jam sessions? 0{+> : God, there have been so many. I've actually recorded some indescribable music with Miles Davis -- long improvisations that I will release at some point. But again, I want to wait until the spirit moves me, you know. Bring those recordings to the public when it feels right. Like release it on his birthday or his death day, when Miles was released from the circle of life and death. GW: In addition to bringing attention to bassist Larry Graham, you've also resurrected Chaka Khan's career. For years, she seemed to be lost, yet she's one of the best soul voices of all time. 0{+> : Chaka is another artist who was temporarily choked by restrictions, contracts and bad business deals. She's free now, free to release as many new songs as she likes. And man, what a voice. One of the pleasures of my life is being able to work with some of my musical heroes, asnd in doing so pay back some dues and have a great time. It was an honor to release Chaka's Come 2 My House and Larry's GCS2000 on my label. I realize I'm part of a musical history and I revere the legacy of my predecessors, so, for instance, when playing live I'll do some of their bombs, like when we do a song like "Cream," we'll segue a snippet of Aretha Franklin's "Chain of Fools" into it. Or we played "Jailhouse Rock" as a tribute to Elvis. GW: It's interesting to hear you cite Elvis Presley, a white artist, as an influence. 0{+> : I was brought up in a black and white world. I dig black and white; night and day, rich and poor, man and woman. I listen to all kinds of music and I want to be judged on the quality of my work, not on what I say, nor on what people claim I am, nor on the color of my skin. But you have to have a certain empathy in order to understand a situation. Like when people made fun of my name change. It was mostly white people, because black people empathize with wanting to change a situation. My last name, Nelson, is really a slave name. A hundred years ago it meant "son of Nell," and it was white slave owners who gave it to their slaves, so why should I go by that name now? Why not do what Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X did? GW: The last time you performed in Brussels, you played a cover version of Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary," but you changed the lyrics around to: "I left a good job in the city, workin' for a man of a record company, a creep earning a living on a nigger's black butt." That was presumably aimed at Warner Bros. Records. Now, you no longer write "slave" on your face. You've renegotiated your contracts and started your own independent record company. Would you care to explain briefly what all that was about, as I'm sure it seemed very confusing to anybody outside of the music business. 0{+> : Okay. Suppose you're a young musician and you want to make a record because you have something to say musically. Well, the record company usually makes you sign away the rights to your songs. In other words, you become a slave to them in the sense that they own the rights to the master recordings of your music for all time, and you're merely an employee. So if you don't own your master, your master owns you. And what we've been trying to do with the NPG label, what it stands for, is trying to create more freedom, including financial freedom, so that artists control their own genesis and can reach a much brighter revelation. GW: On Newpower Soul you seem less preoccupied with producing hit singles than you have in the past. Cynics would say you're unable to write them anymore. 0{+> : Well, that's what they said before "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," too. And that's what they said after Purple Rain, and I had 10 hits after that. And Lovesexy was supposed to be a failure. But I've heard people say that record saved their lives, so I don't care what the media says. I know how I am and what really counts. I just want it more to be like the old days, you know: it's about the book, not the quote. In the old days, you used to buy an album, not a single. I want my records to work as a whole, not a collection of unconnected little bits. GW: Have any lyrics of yours acquired new meaning to you with the passage of time? 0{+> : Yes, my current single, "The One." That went from a love song to a song about respect for the Creator -- God. The lyrics' meaning changed for me after reading the New World translation of the Bible [the Jehovah's Witness translation]. It has to be the New World translation because that's the original one; later translations have been tampered with in order to protect the guilty. There's a Garden-of-Eden feel to "The One." It's about following the highest ideal, and about living up to the goals of the apex, the Creator, "the One." GW: You usually avoid talking about your direct influences, but since you've cited Miles, Chaka and Larry Graham, I'd like to ask you what impact James Brown had on you. 0{+> : James Brown was an inspiration. Was and is. We play JB riffs all the time. I saw James Brown live early in my life, and he inspired me because of the control he had over his band. . . and because of the beautiful dancing girls he had. I wanted both. [laughs] GW: Did you ever fine your musicians when they played bum notes, like James Brown used to do? 0{+> : No, I don't have to. GW: With digital editing, it is now possible to create a situation where you could jam with any artist from the past. Would you ever consider doing something like that? 0{+> : Certainly not. That's the most demonic thing imaginable. Everything is as it is, and it should be. If I was meant to jam with Duke Ellington, we would have lived in the same age. That whole virtual reality thing... it really is demonic. And I am not a demon. Also, what they did with that Beatles song ["Free As a Bird"], manipulating John Lennon's voice to have him singing from across the grave... that'll never happen to me. To prevent that kind of thing from happening is another reason why I want artistic control. GW: Has it ever occurred that something happened while you were recording, a mistake or coincidence, perhaps, that changed the whole song around? 0{+> : I don't believe in coincidence. But one thing leads to another. Playing "Head" live led to "It's Gonna Be a Beautiful Night," in a way. GW: One thing I find fabulous about your songs is that you pay such attention to details. Especially in the ballads, like the siren and the background noise in "Wasted Kisses," on your new album, or the sexy and funny court interlude in the extended version of "I Hate U" on The Gold Experience. 0{+> : I always spend a lot of time and energy thinking about and seeking out those little touches. Attention to detail makes the difference between a good song and a great song. And I meticulously try to put the right sound in the right place, even sounds that you would only notice if I left them out. Sometimes I hear a melody in my head, and it seems like the first color in a painting. And then you can build the rest of the song with other added sounds. You just have to try to be with that first color, like a baby yearns to come to its parents. That's why creating music is really like giving birth. Music is like the universe: The sounds are like the planets, the air and the light fitting together. When I write an arrangement, I always picture a blind person listening to the song. And I choose chords and sounds and percussion instruments which would help clarify the feel of the song to a blind person. For instance, a fat chord can conjure up a fat person, or a particular kind of color, or a particular kind of fabric or setting that I'm singing about. Also, some chords suggest a male, others a female, and some ambient sounds suggest togetherness while others suggest loneliness. But with everything I do, I try to keep that blind person in mind. And I make my musicians pay attention to that, too. Like my bassist, Sonny T., can really play a girl's measurements on his instrument and make you see them. I love the idea of visual sounds. GW: Have you ever composed a particular song because you never heard that kind of song on the radio? 0{+> : Yeah. Absolutely. That happens all the time, I guess. What you've just said is one of the prime reasons why I make music. GW: Some people use your ballads and more sensual songs as a form of aural foreplay. 0{+> : So do I. GW: I was going to ask: What kind of music do you play at home, at night, to get in the mood? 0{+> : The same. GW: You mean you play your own music as foreplay? 0{+> : Yeah. I make music for all occasions. Including ambient music. I composed Kamasutra,which is on Crystal Ball.That's pretty ambient, and great for sex. Hence the title. GW: You've always sung about sex. But then on Emancipation you sang: "You can't call nobody 'cause they'll tell you straight up, come and make love, when you really hate them." So all the time we envied you for great casual sex while you privately didn't like it? 0{+> : Well, obviously now I'm married, so I've found that the spiritual peace that genuine love and passion brings makes anything less than that irrelevant. When I still wrestled with demons, I had moods when I couldn't figure something out and so I ran to vice to sort myself out, like women or too much drink, or working in order to avoid dealing with the problem. GW: Now that you're married, do you still spend as much time in the studio? 0{+> : Yeah, but my wife, Mayte, has me on "studio rehab." People call me a workaholic, but I've always considered that a compliment. John Coltrane played the saxophone 12 hours a day. That's not a maniac, that's a dedicated musician whose spirit drives his body to work so hard. I think that's something to aspire to. People say that I take myself too seriously. I consider that a compliment, too. -- Serge Simonart Source: http://princetext.tripod.com . [Edited 8/4/09 15:49pm] If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

BASS PLAYER

November, 1999 His Highness Gets Down! By Karl Coryat It started out simply enough. The Artist was coming out with a new record, Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic, his people told us. Did we want to come to Minneapolis and do a story on him? The Artist? Is he BASS PLAYER material? Yes, he is. The man can play every instrument sickeningly well, bass certainly being no exception. A listen to any of his early-’80s LPs, on which he played nearly all the parts, bears this out. Being an old Prince fan myself -- who still can’t quite cop the vibe of his disarmingly simple "Let’s Work" [Controversy] -- I jumped at the chance. There was a small catch: The Artist doesn’t allow his interviews to be tape recorded. Perhaps something about losing domain over the sounds he creates. Would he allow me to bring along a stenographer? Apparently, no problem. Several months later I’m in the foyer of Paisley Park, The Artist’s decade-old recording/performance complex just outside the Twin Cities. Accurately described by one journalist as a "musician’s Alice in Wonderland," the plain-exterior place is an eye-feast inside -- painted with countless bright colors, adorned by scores of platinum records and other awards, and outfitted with such necessities as a fitting room (for the two on-staff clothes designers), a faux diner (complete with menus), and a covey of unseen doves, cooing somewhere from 20-plus feet above. While waiting for the Great and Powerful Oz to arrive, I chat with our hired stenographer -- who, like many, was once a Prince fan but hasn’t followed his career since the late ’80s. "Are there names or technical terms I should be familiar with?" Not really -- Larry Graham and "bass" are all that come to mind with the scary moment fast approaching. After reading numerous accounts of The Artist’s often combative demeanor toward journalists, I was still unsure how to keep the conversation steered toward music specifics and away from his usual fashion-mag spiel: God, the millennium, and record-label wars. Finally The Artist appears -- and seems a bit surprised to be meeting a stenographer. "Okay," he hesitates with a slight smile, "but that hasn’t worked out too well in the past." In a flash he commands her to stay put and whisks me off to a studio control room. Before I can even orient myself, the door slams behind me with an airtight thud. Even the Cowardly Lion had Dorothy and friends to quiver with. And a place to run. "I like to start by feeling out a person through conversation," says His Hisness as I begin to scrawl whatever I can in my notebook. "When we talk in here, it’s your word against mine. These walls are completely soundproof. I prefer it this way." Still hoping the real interview had yet to begin, I manage a few general questions about the nature of funk, causing The Artist to wax spiritual in his rich but slightly nasal timbre. Finally he bursts forth with a delighted cackle and then pauses to think. "See that? Would words on a page capture my laugh, or the irony in what I just said? I’d much rather you write about the vibe of our conversation, rather than trying to get my exact words so people can analyze them to death. Why do you need to know exactly what I’m saying? How would that make for a better article?" Do It All Night The Artist cues up a Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic tune. Hands flying over the board, he solos the drums and bass, which he played on Graham’s Moon 4-string (see below). "Hear that? That’s the bass sound. I just turn it up full," he says, pantomiming diming all the knobs at once with the edge of a hand. The old Prince bass feel is right there, ghost-notes and vibrato laden with greasy funk. "There’s bass all over this record, and it’s seriously funky," he adds as he hits stop after only a few bars. "One of the funkiest records of recent years. There’s no good funk happening these days. I’m still waiting for George Clinton to do something." The Artist first picked up bass years after he began playing guitar in 1975 -- which, in turn, was years after he started playing the family piano. "Bass was a necessity," he confesses. "I needed it to make my first album." Already a solid drummer, he translated his rhythmic chops to the bass, and everything fell into place fairly quickly. "That’s the thing about playing both bass and drums -- the parts just lock together. Lenny Kravitz is the same way. If you solo his drum part on 'Are You Gonna Go My Way,’ it sounds like, hey -- he ain’t that good. But put everything on top and it comes together. He just gets high on the funk." So how can a bassist achieve that kind of lock with a live drummer? "I’ll tell you how Larry Graham does it: through his relationship with God. Bootsy plays a little behind the beat -- the way Mavis Staples sings -- but Larry makes the drummer get with him. If he wants to, he can stand up there and go [mimics 16th-note slap line] all night long and never break a sweat." Like the whirling dervishes of Sufi tradition? Exactly. But isn’t it possible to create music as deep as Graham’s without drawing inspiration from a higher power? "No, it isn’t. All things come from God and return to God. I wouldn’t say it necessarily needs to come from a higher place -- but it does need to come from another place." Release It Of course, The Artist is less known for bass than for the controversial eroticism of such early songs as "Head," "Do Me Baby," and "Darling Nikki." Yet it seems many of his more lurid lyrics are backed by bass-heavy arrangements. Is there a connection between the two? "I’ve never thought about that," he muses with a smile. "But no, there isn’t. Bass is primal, and it reminds me of a large posterior - but both spirituality and sexuality originate higher up in the body. I see them as angelic." The Artist’s all-time biggest hit, "When Doves Cry" [Purple Rain], is most distinctive because of its lack of a bass line. The song had one but it was pulled at the last minute. "They were almost done editing the movie," he explains, referring to his big-screen debut in Purple Rain. "‘When Doves Cry’ was the last song to be mixed, and it just wasn’t sounding right." Prince was sitting with his head on the console listening to a rough mix when one of his singers, Jill Jones, walked in and asked what was wrong. "It was just sounding too conventional, like every other song with drums and bass and keyboards. So I said, ‘If I could have it my way it would sound like this,’ and I pulled the bass out of the mix. She said, ‘Why don’t you have it your way?’" From the beginning Prince had an inkling the tune would be better bass-free, even though he hated to see the part go. "Sometimes your brain kind of splits in two -- your ego tells you one thing, and the rest of you says something else. You have to go with what you know is right." So bass can work against a song then? "Not necessarily. ‘When Doves Cry’ does have bass in it -- the bass is in the kick drum. It’s the same with ‘Kiss’ [Parade]: The bass is in the tone of the reverb on the kick. Bass is a lot more than that instrument over there. Bass to me means B-A-S-E. B-A-S-S is a fish." My Name Is Prince Prince’s first four albums were basically one-man efforts, with a few guest spots (though he kept all bass duties to himself). One of the most prolific artists in rock history, he also wrote, produced, and recorded for others -- most notably fellow Minneapolis band The Time. In fact he performed nearly all the instrumental parts on the Time’s first two records, choosing to take only a production credit under the pseudonym Jamie Starr (which he also used for credits on two of his own records). "I was just getting tired of seeing my name," he explains. "If you give away an idea, you still own that idea. In fact, giving it away strengthens it. Why do people feel they have to take credit for everything they do? Ego -- that’s the only reason." He adopted yet another pre-symbol nom de plume, Camille, for "female" sped-up vocal parts. Ever the gender bender, Prince had begun performing in women’s undergarments as early as 1979. His opening slot on a Rolling Stones tour, where he was pelted with garbage by disco-hating hooligans, is now part of rock legend. "Don’t say that was because of me," he admonishes, wagging a finger. "That was the audience doing that. I’m sure wearing underwear and a trench coat didn’t help matters - but if you throw trash at anybody, it’s because you weren’t trained right at home." Starting with 1982’s 1999, Prince began crediting a band, the Revolution, on his recordings. Though he still played many of the parts, over the next few albums the Revolution played an increasingly important role. "I wanted community more than anything else. These days if I have Rhonda [S., formerly The Artist’s primary live bassist] play on something, she’ll bring in her Jaco influence, which is something I wouldn’t add if I played it myself. I did listen to Jaco -- I love his Joni Mitchell stuff -- but I never wanted to play like him." The Artist still raves about the original Revolution bassist, Brown Mark (who took over for Andre Simone), calling him the tightest bass player next to Graham himself. The latest version of New Power Generation is The Artist’s most skilled band to date; in addition to Graham, the group’s Mill City Music Festival performance included James Brown saxophonist Maceo Parker, who also has free rein over the Paisley Park facilities for his own projects. Of course, Graham fits seamlessly into New Power Generation -- and you can be sure The Artist never needs to tell him to play less and listen more. The Beautiful Ones The interview is winding down. With most of my questions answered (or at least chewed up and spit out), I pose another: Of all the bass lines you’ve created and played over the years, which stands out the most? As if he’s answered the query in every interview, he instantly volleys back, "777-9311" (the Time’s What Time Is It?). Why? "Because nobody can play that line like I can. It’s like ‘Hair’ [1973’s Graham Central Station, Warner Bros.], or ‘Lopsy Lu’ [Stanley Clarke, Epic] - nobody can play those parts better than Larry and Stanley." I mention I was glad to hear him dig up "Let’s Work" for the previous night’s show. "Hmmm -- that might be a tie with ‘777.’" The Artist gets up and heads over to the bass sitting in the corner but then waves a hand at it. "Oh, 5-string -- a mutant animal." I start to scribble down the quote. "Don’t print that! People will say I don’t like the 5-string because I can’t play it. We do have to keep an open mind to things. We need to be open to evolution." The Artist picks up a phone receiver and -- without dialing -- summons Hans-Martin Buff, his engineer, who fetches Graham’s white Moon bass. "Now imagine me teaching Larry Graham how to play this," he scoffs as he plugs into the board and lays into the "Let’s Work" line. With no rhythm track, his feel isn’t quite as slinky as on record, but all the elements are there -- subtle ghost-notes, vibrato, funky push-and-pull. Suddenly he stops and hands me the bass. What? "Let’s see what you can do," he says. (Sure am glad I’m not a spy.) As I grab the neck he snatches my notebook and crosses his legs. "Now I’m gonna ask you some questions," he toys. Stalling, I inquire about the xlr jack on the upper horn. "For his mike," he says, as if I needed to ask. I tentatively try out a generic finger-funk groove in A. (I am not going to slap in front of the "Let’s Work" guy.) "That’s the sound, isn’t it?," asks The Artist. The tone is indeed perfect, but aside from the very low action and super-zingy strings, there’s nothing terribly magical about the instrument’s feel. And of course it sounds like me coming out of the monitors, not Graham. "Do you ever practice?" I ask, handing back the bass. "Do you get rusty when you don’t play for a while?" "No," he sighs, almost bored. "Playing is like breathing now." We get up and start to move to the door. "I was a little worried there at the beginning," he says. "But it wasn’t that bad, was it?" And I’m out of there - but not before one last awkward moment as I shake his hand, unsure how to address him. "It was very interesting. Thank you. Um, yeah -- thanks." Hoo-boy. Beginning to sweat, I try to explain I had planned a Q&A in which I’d ask very specific, technical questions that would interest only other musicians -- in a context where bassists would want to absorb every word. "Then ask me something," he replies. "Ask me any question on that list of yours, and we’ll see what happens." Skipping my planned opening query, I quick-search the page for the most technical question I can find. "Okay. Do you have a tone recipe for great funk bass?" Without a pause: "Larry Graham. Larry Graham is my teacher." The Artist continues, veering quickly away from funk tone to God, to all of us being connected by the Spirit -- but just as suddenly he claps his hands sharply, jumps up from his seat, and bellows a joyful noise. "Why do you need a stenographer to type out ‘Larry Graham’? That’s my answer to your question -- it is all you need to know. Just write down ‘Larry Graham’ in your notebook!" Time to find that man behind the curtain. The Artist’s gaze shifts slightly sidelong. "Why do you want a witness, anyway? This isn’t a deposition." A pause. "Are you a spy?" he asks with a sly smile. "Who sent you here? What did you do before you worked for this magazine? Are you working for someone else? Did somebody put something in your ear?" Resisting an urge to flee, I try to think of something -- anything -- to settle myself and keep the interview intact. "Okay. No stenographer then. But the least I can do is go out there and tell her she’s free to leave." "Fine," says The Artist with a flick of his hand, turning toward the massive console. "I’ll be right here." When I return less than a minute later, he’s singing into a mike poised over the board. "There," he purrs as I sit back down, hoping some color is returning to my face. "Now we can have a conversation." Nothing Compares 2 U Things went much smoother once I had been paisley-whipped into shape. Yet it seemed no matter what I asked, the conversation turned to either God, Larry Graham, or both -- The Artist freely admitting he modeled his bass style after Graham’s. Prince first briefly met the slap pioneer at a Warner Bros. company picnic in 1978, by which time Larry had moved on from Sly & the Family Stone and was a star in his own right fronting Graham Central Station. The two met again a few years later, this time at a Nashville jam. "Larry’s wife came up to him and pulled an effects box and cord out of her purse," The Artist remembers warmly. "Now that’s love." But Graham and the man he calls "Little Brother" didn’t develop a real relationship until the ’90s -- "relationship" perhaps being an inadequate description. "Here’s a guy who has a brother hug for you every day," says The Artist. "And once Larry taught me The Truth, everything changed. My agoraphobia went away. I used to have nightmares about going to the mall, with everyone looking at me strange. No more." The couple forged an ocean-deep spiritual connection -- The Artist is a Seventh Day Adventist, Graham a Jehovah’s Witness. "I mean, Larry still goes around knocking on doors telling people The Truth. You don’t see me doing that!" The Artist invited his "older brother" to Minneapolis, set him up with a house of his own, and welcomed him into the Paisley Park family, "signing" him to a handshake-based deal with NPG Records. Before long Graham was playing with The Artist’s band New Power Generation and feasting Graham Central Station on Paisley’s incredible rehearsal and studio facilities. And ever since, after years of always picking up the bass for at least a few numbers per set, The Artist has hardly touched the instrument onstage. "I can’t even physically reach for it anymore," he laughs. Why? "I don’t know. I hope it’s out of respect for Larry, and not because I feel inadequate compared to him." Baby I’m A Star The night before our interview, New Power Generation and GCS co-headlined the last night of the Mill City Music Festival, a kind of Woodstock-in-a-parking-lot in Minneapolis’s warehouse district. The Artist’s performance was as energetic as any ’80s Prince show, the only down moments coming with his between-song proselytizing and boasting. "People say to me, ‘Congratulations on your new [record] deal’ But they ought to go find the president of the record company and congratulate him!" Years ago that would have been a sure cheer line -- but on this night the mostly 30-something crowd stood reserved, waiting for the next "Let’s Go Crazy" or "U Got the Look" sprinkled among the newer, unfamiliar tunes. Later The Artist reclined on a riser and pouted, "You might love Larry Graham, and you might love Morris Day -- but you don’t love me!" Yet The Artist has plenty to say about the dangers of ego in a musical context. "My first bass player was Andre Cymone," he remembers, "and Andre’s ego always got in the way of his playing. He always played on top of the beat, and I’m convinced that was just because he wanted to be heard. Andre and I would fight every night, because I was always trying to get him to sound like Larry Graham. Larry’s happy just going [mimics thumping open-string quarter-notes] -- he’s not interested in showing off. When you’re showing off it means you aren’t listening." The Artist shifts gears to describe a present-day rehearsal and grows excited again. "Space!" he bellows. "Space is what it’s all about. I’m always telling people in rehearsal you’ve got to shut up once in a while. Solo spotlights are fun and everything, but if you make music people want to hear, they’ll keep that tape. You can listen to one groove all night, but if everyone’s playing all over the place all night and not hearing each other - not respecting the music - ain’t nobody gonna want to listen." Housequakin’ The Artist currently owns eight basses, according to his tech, Takumi (who also works for Larry Graham). When he picks up a bass onstage, he favors his white Warwick Thumb "Eye Bass" (so named because of the eye painted on the front), a white fretless Warwick Thumb, or his custom Lakland with a fist-shaped headstock. Other basses include an old Guild Pilot and a gold-colored Ibanez Soundgear. And even though he’s not likely to need it, The Artist has Takumi set up his bass rig at every show, just in case the spirit moves him to strap on a 4-string. Takumi covers up the rig onstage and doesn’t reveal any further details about it, since The Artist doesn’t endorse equipment. The Artist plays bass on nearly all of the Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic tracks. (Rhonda S. appears on two songs.) For most of his parts The Artist used Graham’s Moon bass with Bartolini pickups; when the Moon was unavailable he used the Warwick Eye Bass. Engineer Hans-Martin Buff ran the signal into an Avalon U5 active DI, either a Demidio or Neve mike preamp, a Summit Audio compressor, and sometimes an API 550 EQ. The Artist rarely mikes a bass amp in the studio. The only bass effects on the record are a Zoom 9030 (usually on its "slap wah" setting) and a Danelectro Fab Tone pedal for fuzz. Career File 1958 Born Prince Rogers Nelson in Minneapolis, Minnesota 1975 Begins playing guitar 1978 Signs first deal with Warner Bros; begins playing bass; releases first album 1980 Adopts androgynous, sex-obsessed image with third album, Dirty Mind 1982 Releases first smash-hit record, 1999, propelled by single "Little Red Corvette"; eventually sells over three million copies 1984 Becomes a superstar with ten-million-selling Purple Rain, appearing in semi-autobiographical film of same name 1987 Cancels release of Black Album weeks before it was to hit stores; with several thousand copies already pressed, Black Album becomes perhaps the most bootlegged record of all time. Warner Bros. eventually releases it officially in 1994 as a limited edition. 1993 Legally changes name to a symbol, which becomes emblem of Politically Incorrect host Bill Maher’s "Get Over Yourself" award. When Warner Bros. refuses to release The Gold Experience over worries about market saturation, The Artist Formerly Known As Prince makes public his feud with the label. 1995 Now known simply as The Artist, makes appearances with slave written on face to protest Warner’s refusal to sell him his master tapes 1996 No longer bound by the Warner contract, releases triple-CD set Emancipation on his own NPG Records 1998 Sells four-CD set Crystal Ball through Web site, www.1800newfunk.com, and 1-800-NEW-FUNK 1999 Releases EP 1999 - The New Master, with seven updated versions of classic Prince song. Signs one-off distribution deal with Arista to release Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic. Source: http://princetext.tripod.com If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

squirrelgrease said:

October 1998

THE ARTIST Representatives of the Artist arrange for a meeting -- a secret rendezvous -- between myself and the gifted one at The Hit Factory in New York City. . . The Artist, a platinum jewel attached to his ear, arrives clad in black and carrying a transparent walking stick with blue sparkling stars. His is everything I could hope for, as gloriously ineffable as his name is unpronounceable. Guitar World: You won't allow your interviews with the press to be tape recorded. Why? Presumably, you'd like to be able to guarantee more accurate representation of our conversation with a recorder. 0{+> : To me, a tape recorder is like having a contract. And I don't want to have a contract with you. I don't want this to be business. I want this to be a normal conversation about something that we're hopefully both passionate about: music. And when there is no tape recorder, our relationship is based on trust. So if you write lies, you're the one betraying that trust, and you'd be the one soaking up all that negative energy. But I trust you, so we don't need a tape recorder. And I can talk now, because I'm free. A lot of my music has to do with being free. I'm not chained anymore. And being married to Mayte has made me feel more comfortable with speaking in public. GW: Earlier this year you released Crystal Ball, a mammoth five-CD set. It contains some incredible outtakes and a number of unreleased tracks, but still no live music. You're hailed as being one of our best live performers. You've been doing incredible shows for years. Why have you avoided releasing live material? 0{+> : I have everything on tape, man, including all the informal jams. I record everything I do, just like Jimi Hendrix did. And eventually a lot of it will be released. To me, Crystal Ball was a test case. I was testing the water to see if people would buy music over the internet, and whether they would be receptive to a five-CD set. Since the album was a success, it leads me to believe that the whole interactive thing offers great possibilities. I mean, why not make a five-CD live album, with people on the internet choosing their favorite tracks? Why not poll the fans on our web site and let them compile it? All this will happen. Soon. For example, I just performed and recorded a 45-minute jam with Larry Graham called "The War," which I edited down to 26 minutes. It's a fantastic track. In the past, my old record company would never allow me to release something like that. Now that I have my own label, I can think about releasing that kind of stuff. GW: What were some of your most memorable jam sessions? 0{+> : God, there have been so many. I've actually recorded some indescribable music with Miles Davis -- long improvisations that I will release at some point. But again, I want to wait until the spirit moves me, you know. Bring those recordings to the public when it feels right. Like release it on his birthday or his death day, when Miles was released from the circle of life and death. GW: In addition to bringing attention to bassist Larry Graham, you've also resurrected Chaka Khan's career. For years, she seemed to be lost, yet she's one of the best soul voices of all time. 0{+> : Chaka is another artist who was temporarily choked by restrictions, contracts and bad business deals. She's free now, free to release as many new songs as she likes. And man, what a voice. One of the pleasures of my life is being able to work with some of my musical heroes, asnd in doing so pay back some dues and have a great time. It was an honor to release Chaka's Come 2 My House and Larry's GCS2000 on my label. I realize I'm part of a musical history and I revere the legacy of my predecessors, so, for instance, when playing live I'll do some of their bombs, like when we do a song like "Cream," we'll segue a snippet of Aretha Franklin's "Chain of Fools" into it. Or we played "Jailhouse Rock" as a tribute to Elvis. GW: It's interesting to hear you cite Elvis Presley, a white artist, as an influence. 0{+> : I was brought up in a black and white world. I dig black and white; night and day, rich and poor, man and woman. I listen to all kinds of music and I want to be judged on the quality of my work, not on what I say, nor on what people claim I am, nor on the color of my skin. But you have to have a certain empathy in order to understand a situation. Like when people made fun of my name change. It was mostly white people, because black people empathize with wanting to change a situation. My last name, Nelson, is really a slave name. A hundred years ago it meant "son of Nell," and it was white slave owners who gave it to their slaves, so why should I go by that name now? Why not do what Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X did? GW: The last time you performed in Brussels, you played a cover version of Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary," but you changed the lyrics around to: "I left a good job in the city, workin' for a man of a record company, a creep earning a living on a nigger's black butt." That was presumably aimed at Warner Bros. Records. Now, you no longer write "slave" on your face. You've renegotiated your contracts and started your own independent record company. Would you care to explain briefly what all that was about, as I'm sure it seemed very confusing to anybody outside of the music business. 0{+> : Okay. Suppose you're a young musician and you want to make a record because you have something to say musically. Well, the record company usually makes you sign away the rights to your songs. In other words, you become a slave to them in the sense that they own the rights to the master recordings of your music for all time, and you're merely an employee. So if you don't own your master, your master owns you. And what we've been trying to do with the NPG label, what it stands for, is trying to create more freedom, including financial freedom, so that artists control their own genesis and can reach a much brighter revelation. GW: On Newpower Soul you seem less preoccupied with producing hit singles than you have in the past. Cynics would say you're unable to write them anymore. 0{+> : Well, that's what they said before "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," too. And that's what they said after Purple Rain, and I had 10 hits after that. And Lovesexy was supposed to be a failure. But I've heard people say that record saved their lives, so I don't care what the media says. I know how I am and what really counts. I just want it more to be like the old days, you know: it's about the book, not the quote. In the old days, you used to buy an album, not a single. I want my records to work as a whole, not a collection of unconnected little bits. GW: Have any lyrics of yours acquired new meaning to you with the passage of time? 0{+> : Yes, my current single, "The One." That went from a love song to a song about respect for the Creator -- God. The lyrics' meaning changed for me after reading the New World translation of the Bible [the Jehovah's Witness translation]. It has to be the New World translation because that's the original one; later translations have been tampered with in order to protect the guilty. There's a Garden-of-Eden feel to "The One." It's about following the highest ideal, and about living up to the goals of the apex, the Creator, "the One." GW: You usually avoid talking about your direct influences, but since you've cited Miles, Chaka and Larry Graham, I'd like to ask you what impact James Brown had on you. 0{+> : James Brown was an inspiration. Was and is. We play JB riffs all the time. I saw James Brown live early in my life, and he inspired me because of the control he had over his band. . . and because of the beautiful dancing girls he had. I wanted both. [laughs] GW: Did you ever fine your musicians when they played bum notes, like James Brown used to do? 0{+> : No, I don't have to. GW: With digital editing, it is now possible to create a situation where you could jam with any artist from the past. Would you ever consider doing something like that? 0{+> : Certainly not. That's the most demonic thing imaginable. Everything is as it is, and it should be. If I was meant to jam with Duke Ellington, we would have lived in the same age. That whole virtual reality thing... it really is demonic. And I am not a demon. Also, what they did with that Beatles song ["Free As a Bird"], manipulating John Lennon's voice to have him singing from across the grave... that'll never happen to me. To prevent that kind of thing from happening is another reason why I want artistic control. GW: Has it ever occurred that something happened while you were recording, a mistake or coincidence, perhaps, that changed the whole song around? 0{+> : I don't believe in coincidence. But one thing leads to another. Playing "Head" live led to "It's Gonna Be a Beautiful Night," in a way. GW: One thing I find fabulous about your songs is that you pay such attention to details. Especially in the ballads, like the siren and the background noise in "Wasted Kisses," on your new album, or the sexy and funny court interlude in the extended version of "I Hate U" on The Gold Experience. 0{+> : I always spend a lot of time and energy thinking about and seeking out those little touches. Attention to detail makes the difference between a good song and a great song. And I meticulously try to put the right sound in the right place, even sounds that you would only notice if I left them out. Sometimes I hear a melody in my head, and it seems like the first color in a painting. And then you can build the rest of the song with other added sounds. You just have to try to be with that first color, like a baby yearns to come to its parents. That's why creating music is really like giving birth. Music is like the universe: The sounds are like the planets, the air and the light fitting together. When I write an arrangement, I always picture a blind person listening to the song. And I choose chords and sounds and percussion instruments which would help clarify the feel of the song to a blind person. For instance, a fat chord can conjure up a fat person, or a particular kind of color, or a particular kind of fabric or setting that I'm singing about. Also, some chords suggest a male, others a female, and some ambient sounds suggest togetherness while others suggest loneliness. But with everything I do, I try to keep that blind person in mind. And I make my musicians pay attention to that, too. Like my bassist, Sonny T., can really play a girl's measurements on his instrument and make you see them. I love the idea of visual sounds. GW: Have you ever composed a particular song because you never heard that kind of song on the radio? 0{+> : Yeah. Absolutely. That happens all the time, I guess. What you've just said is one of the prime reasons why I make music. GW: Some people use your ballads and more sensual songs as a form of aural foreplay. 0{+> : So do I. GW: I was going to ask: What kind of music do you play at home, at night, to get in the mood? 0{+> : The same. GW: You mean you play your own music as foreplay? 0{+> : Yeah. I make music for all occasions. Including ambient music. I composed Kamasutra,which is on Crystal Ball.That's pretty ambient, and great for sex. Hence the title. GW: You've always sung about sex. But then on Emancipation you sang: "You can't call nobody 'cause they'll tell you straight up, come and make love, when you really hate them." So all the time we envied you for great casual sex while you privately didn't like it? 0{+> : Well, obviously now I'm married, so I've found that the spiritual peace that genuine love and passion brings makes anything less than that irrelevant. When I still wrestled with demons, I had moods when I couldn't figure something out and so I ran to vice to sort myself out, like women or too much drink, or working in order to avoid dealing with the problem. GW: Now that you're married, do you still spend as much time in the studio? 0{+> : Yeah, but my wife, Mayte, has me on "studio rehab." People call me a workaholic, but I've always considered that a compliment. John Coltrane played the saxophone 12 hours a day. That's not a maniac, that's a dedicated musician whose spirit drives his body to work so hard. I think that's something to aspire to. People say that I take myself too seriously. I consider that a compliment, too. -- Serge Simonart Source: http://princetext.tripod.com This is not the right article/interview for this cover. This interview was for another Guitar World Prince feature at a later time when he wasn't on the cover. www.arjunmusic.com

www.myspace.com/arjunmusic www.cdbaby.com/arjuntunes ARJUN: funk-indie-rock-jazz-groove trio just released their debut album entitled, "Pieces" Instrumental heavy grooves and improvisation. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Mike Scott interview. Keep It Funky!

Get Your Groove On with Help from Prince/Justin Timberlake Guitarist Mike Scott By Jude Gold... You’ve heard the story before: A posse of musicians stuffs a mountain of instruments into a car and heads west to Hollywood to take a shot at the big time. Mike Scott’s road to the main stage, however, took a big right turn to the north. In the early ’90s, Scott said goodbye to his hometown of Washington D.C. when he, a bass player, and a drummer crammed all their gear into a Ford Escort and drove 22 hours to Minneapolis. They weren’t relocating to the Minnesota city with lofty ambitions of scoring work with Prince, production moguls Terry Lewis and Jimmy Jam, or any of the other R&B kingpins that called the place home. They were there to team up with Radiant, a D.C.-based cover band working the “Marriott circuit,” doing month-long stints in hotel lounges. The band broke up mere weeks after Scott’s arrival. “The other guys went back to D.C.,” says Scott, “but I said, ‘I’m staying here,’ because I saw that on the local level, the Minneapolis scene was just virgin. There were no funky black guitar players out there, not one.” Scott’s first lucky break occurred at a club where Michael Bland, Prince’s drummer at the time, was playing in a cover band. “People were like, ‘Man, nobody sits in with them,’ but I just walked up and said, ‘I wanna sit in,’ and they said, ‘Well, come on then.’ I played with them that night and the next day my phone started ringing and soon the gigs came rolling in. I eventually hooked up with Sounds of Blackness, who were signed to Jam and Lewis. When I met Jam and Lewis, they immediately put me to work on all kinds of albums they were producing—Mariah Carey, Lionel Richie, Gladys Knight, Janet Jackson. Those guys were busy. I worked for them for 12 years. “When Jam and Lewis moved to L.A., whew, things dried up. [Laughs.] But I got with Prince one day in 1996. Then he asked me to come to a rehearsal the next day, and then the next day after that. Next thing I know, I’m on a tour bus with them, despite never officially being told I’m in the band. I’ve been with Prince on and off ever since.” As if Prince’s recent Musicology tour wasn’t exciting enough, Scott has now landed the lead guitar spot on one of the most elaborate touring shows of all time—Justin Timberlake’s massive FutureSex/LoveShow tour. How does Scott score all these top-shelf R&B gigs? Well, for one, he is a ripping lead player. “One night Prince’s guitar went out a half a bar before his big solo on ‘Purple Rain,’ so he had me take the solo,” says Scott. “I tore the ass out of that thing. Afterwards, he said, ‘You’ll never get that solo again.’” [Laughs.] Really, though, despite his versatility, it’s Scott’s fluency in the universal language of groove that keeps his phone ringing with dream gigs. Whether he’s playing rhythm or lead, Scott’s got a pulverizing attack that’s as lively and loose as it is metronomically perfect—and visceral. He kills his .010-.046 DR strings with one of the heaviest picks in production today (a 2.0mm Dunlop Delrin 500), yet the defenseless wires don’t seem to mind and rarely break on him. It’s as if they forgive his punishing heavyweight strumming because his notes are timed so well—much the way your eardrums forgive a hard-hitting drummer with a phat pocket. Chicka, Chank, Choke In the back lounge of the band bus behind the arena, Mike Scott uncases a Paul Reed Smith Hollowbody II (which, aside from perhaps his Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion, seems to be his go-to guitar), plugs into a practice amp, and starts warming up with a variety of licks that show deep funk roots. He touches on everyone from Tony Maiden to Ernie Isley, James Brown to Chuck Brown. Before you begin to tackle funk licks, make sure you’ve got three basic funk attacks down. We’ll call the first one [Ex. 1] the chicka, because that’s the sound you hear when you mute a chord with your fretting hand and strike it with quick down/up strums. The second, the chank, is the onomatopoeic name we’ll apply to an un-muted chord struck on the high strings and made staccato by a quick release of the fretting-hand fingers [Ex. 2]. The choke [Ex. 3] is necessary when you need to absolutely murder single notes with a free-swinging picking hand and don’t want the other five strings to ring. (Mute the unused strings with unused fretting fingers, including, when necessary, the fretting-hand thumb.) See if you can play Scott’s scratchy single-note lick in Ex. 4 using the choke to prevent extra string jangle. Playing Ex. 5, Scott demonstrates three other funk stylings you’ll need to own—chord vibrato (as applied to all four notes in the G7#9 chord that opens each measure), double-note bends (bar 1), and percussive sweeps (such as the six-string muted sweep in bar 2). Go-Go Guitar If there’s one groove Scott plays that truly reflects his roots in D.C. funk, it’s the one that finds him muting the strings with his fretting hand somewhere above the 19th-fret and strumming sixteenth-notes (with a few triplets thrown in) with a “swing sixteenths” feel [Ex. 6]. The chicka-chicka strumming sounds like a shaker or a hi-hat. “In D.C., there’s a music called go-go,” says Scott, expanding the lick in Ex. 7 by adding 19th-fret harmonics in the repeated bar and a satisfying turnaround in bar 4. “In go-go, percussion is the most important thing, and the guitar often ends up playing percussion, so to speak. This is a little groove Chuck Brown—the ‘Godfather of go-go,’ as they call him—sort of came up with. Throw in those harmonics and you end up sounding kind of like a conga player.” Or, you could say, the harmonics evoke the dual-cowbell patterns that are a trademark of go-go. “The strumming-hand rhythm’s got to be consistent,” says Scott. “Thinking of the guitar more as a percussion instrument makes it a lot easier to find your place in a song and make it funky—to find that hole.” Flutter Funk Asked what he might nominate as the funkiest guitar riff of all time, Scott is hard-pressed to choose just one. “Hmm, could be just about anything by James Brown,” he muses, “or perhaps this lick [Ex. 8], which is like the guitar part on ‘Funky Stuff’ [by Kool & the Gang]—I love that. One guy I always liked was Tony Maiden and that fluttery stuff he played with Chaka Khan.” To demonstrate the flutter-funk style—now a staple of many R&B songs and a must-know feel for any aspiring funk guitarist—Scott plays Ex. 9. “It’s kind of like Ernie Isley on ‘Who’s That Lady,’” he says. “On the F#m7 and C#m7 chords, let all the notes ring and add the hammered and pulled notes on various strings with your 4th finger. This style is all about the 4th finger.” Chicken Grease Another fluttery funk essential is the straight-sixteenths approach to strumming chords popularized by Prince (think “Sexy M.F.”), the Average White Band (intro to “Pick Up the Pieces”), and other groups. “Prince calls it ‘chicken grease,’” says Scott, demonstrating such funk gristle by strumming Ex. 10 with a consistent yet almost feather-light touch. “Prince and I have a good musical rapport onstage. If he is playing low, I play high, or if he’s playing single notes I’ll play chords. It’s the same thing Skip Dorsey and I do on the Timberlake gig. And when Prince wants to change up the groove, he’ll often say, ‘Mike Scott chicken grease!’ and I’ll go into some of these droning sixteenths for a while. If he wants to get out of it, he’ll say something like ‘On the one,’ and we’ll break.” Gotta Want It Asked how he would define what it means to be funky, Scott recalls his high school days. “I went to Duke Ellington School of the Arts in D.C.,” he says. “There were a lot of guitar players there, and people always used to tell me, ‘Mike Scott, this guy might be better than you, and that guy might be faster, but you’re the funkiest cat in school.’ For me, being funky means being able to find the missing groove—to listen to the other musicians and find that one syncopation they’re missing; that one sixteenth-note somewhere that’s not in the groove. I always hear that extra part and I’m like, ‘Man, I want that.’” Armed with my own guitar, I decide to put Scott’s funk powers to the test. I play a scratchy, syncopated two-bar funk loop [Gtr. 1 of Ex. 11] and ask him to find the “missing part.” After hearing my riff only twice, he leaps in with Gtr. 2’s slippery take on Jimmy Nolen-style ninth-chord funk. Our two riffs lock like cogs in a Swiss watch. “See, you hit that groove, and your groove was funky,” Scott tells me. “But there were these spaces and holes I was seeing that would make the two of us much funkier together.” The whole is funkier than the sum of its parts. Visit Mike Scott online at myspace.com/iammikescott. THE NO. 1 RULE OF FUNK “The most important thing about playing funk is to stay in your spot,” says Mike Scott, who learned this imperative working for years under one of the funkiest bandleaders ever to strut across a stage. “Playing with Prince is like going to school—funk school. He’d say, ‘Don’t play one extra note except for the part I showed you, and don’t worry—it’s gonna be funky.’ Sometimes I’d get bored holding that James Brown chord for half an hour, but I’d listen back later to what we’d been doing, and it’d be so funky. That’s the biggest thing I learned from Prince—hold that pocket. It’s your natural inclination to want to add fills and riffs—to ‘show your butt’ a little—but don’t deviate.” —JG BIG GIG, SMALL AMP Far below the limelight and laser beams; beneath the feet of Justin Timberlake and his troupe of dancers, singers, and musicians; tucked inside the multi-tiered, fully hydraulic stage, is a cozy den in which all of Mike Scott’s spare guitars (as well as those of co-guitarist Skip Dorsey) reside. “The stage takes a while to set up,” says Scott. “The second night of the tour we barely got a soundcheck, and in the middle of the set, we had major wireless problems. Suddenly, my guitar was coming out of Skip’s rig and vice-versa. We had to go with cables for the rest of the night, which affected the show, because we usually move around the stage a lot.” Luckily, the concerts—and guitar rigs—have been running near-seamlessly ever since. Despite its massive acreage, though, Timberlake’s sprawling stage is unable to accommodate Scott’s Genz-Benz El Diablo or Hughes & Kettner TriAmp half-stacks. “The keyboard risers rotate and move around, and they cut right into our area,” explains Scott. “I can’t even fit my Fishman acoustic amp up there. The only amp I use on stage is a Mesa Lone Star 1x12 combo. It suits the gig well because it has a clear, bell-like top end and a lot of body in the mids—and because it fits.” —JG STOMP! Despite keeping his Mesa Lone Star combo’s footswitch (right) well within stomping distance, Mike Scott rarely kicks the amp into overdrive mode. Instead, for leads, he typically drives the clean channel (sometimes while the amp’s boost function is engaged) with a Fulltone OCD overdrive. His Pedal Pad pedalboard also features an Ernie Ball volume pedal, a Fulltone Clyde wah, a Dunlop Rotovibe, a Fulltone Full-Drive 2, a Boss Digital Delay, two Boss TU-2 tuners (one for acoustic), a Boss Octaver, an MXR Custom Shop GT-OD, an EBS Bass IQ envelope filter, a Dunlop pick holder, and an onboard electric fan. Scott wires his pedalboard with Planet Waves cables (“I use the ones with the gold-plated connectors. You can really hear the difference between these and ordinary cables”) What you can’t see is Scott’s AKG wireless system and Fulltone Fat-Boost—the latter of which is mounted inside the pedalboard. “It’s not a problem having it hidden in there because I never turn it off,” says Scott of the pedal. “It pushes the front end of the amp just enough to give it some extra sparkle. There’s no distortion. It doesn’t change the character of the guitar.” —JG Source: http://www.guitarplayer.c...r-07/27272 If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

ARJUN said: squirrelgrease said: This is not the right article/interview for this cover. This interview was for another Guitar World Prince feature at a later time when he wasn't on the cover. You are exactly right. The cover is from 1994 (the one that was supposed to have The Undertaker CD glued to it). Anyone have the 1994 text? If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

squirrelgrease said: ARJUN said: This is not the right article/interview for this cover. This interview was for another Guitar World Prince feature at a later time when he wasn't on the cover. You are exactly right. The cover is from 1994 (the one that was supposed to have The Undertaker CD glued to it). Anyone have the 1994 text? Well this is the article I was originally talking about - anyone have this? Ur always on my mind...DAY AND NIGHT, BABY ALL THE TIME...U mean so much 2 me...A LOVE LIKE OURS... just had 2 be | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

squirrelgrease said: ARJUN said: This is not the right article/interview for this cover. This interview was for another Guitar World Prince feature at a later time when he wasn't on the cover. You are exactly right. The cover is from 1994 (the one that was supposed to have The Undertaker CD glued to it). Anyone have the 1994 text? I have it somewhere, but still can't find it.. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

zaza said: squirrelgrease said: You are exactly right. The cover is from 1994 (the one that was supposed to have The Undertaker CD glued to it). Anyone have the 1994 text? I have it somewhere, but still can't find it.. I have the magazine too, but who knows where I put that. If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

1994 Guitar World

If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

And some good tabs are here http://pages.prodigy.net/...ra/tab.htm | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

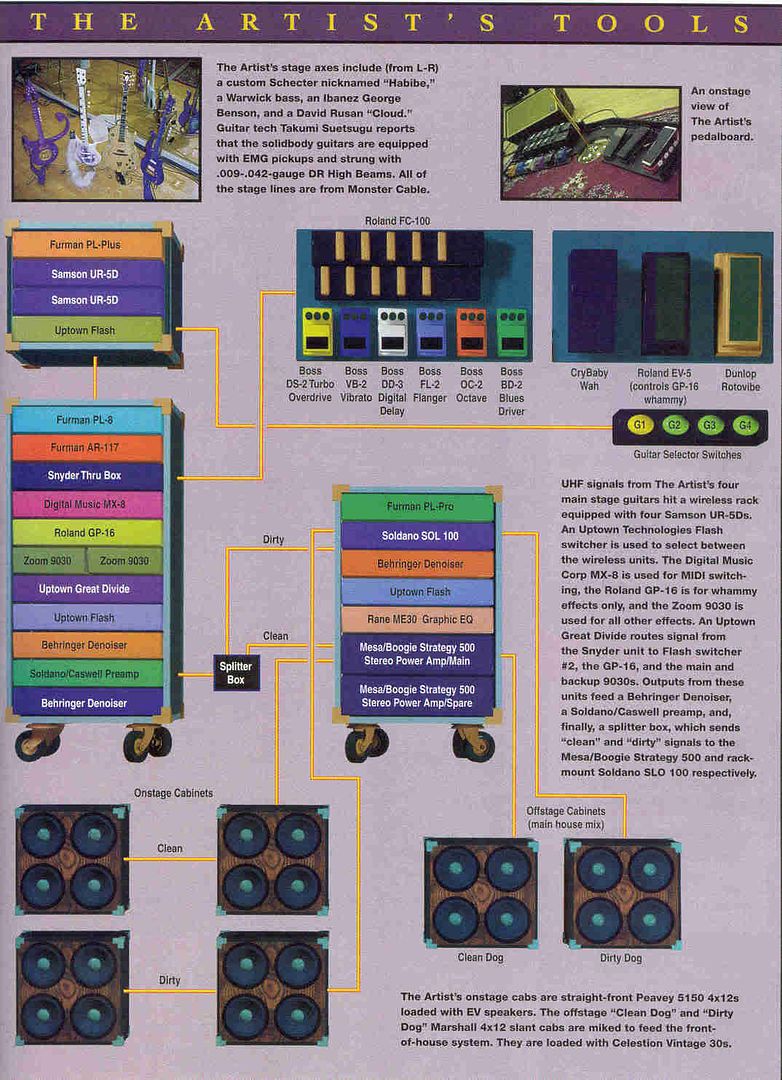

The set up from a few years back:

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Setup from the 2007 London shows (now you can even copy the settings

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

squirrelgrease said:

BASS PLAYER

November, 1999 His Highness Gets Down! By Karl Coryat It started out simply enough. The Artist was coming out with a new record, Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic, his people told us. Did we want to come to Minneapolis and do a story on him? thank you for that. interesting read. gave me some inspiration for the new bass i wanna get "Sisters and brothers in the purple underground, find peace of mind in the pop sound!" | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

jethrouk said: squirrelgrease said:

BASS PLAYER

November, 1999 His Highness Gets Down! By Karl Coryat It started out simply enough. The Artist was coming out with a new record, Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic, his people told us. Did we want to come to Minneapolis and do a story on him? thank you for that. interesting read. gave me some inspiration for the new bass i wanna get If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Thanks David1974! Awesome pix. Love this kind of detail. If prince.org were to be made idiot proof, someone would just invent a better idiot. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

horseluvaphat said: Hey guys,

I'm hoping one of you will be able to help me with the following. Sometime in the early 90's Prince did an interview for a now-defunct guitar magazine. I think it was "Guitar World" if I'm not mistaken. It included an article, a description of his rig and also some tablature. I'd love it if anyone has any scans if they could post them (I'm primarily interested in the tabs). Speaking of which, does anyone have any good sites for Prince guitar tab? Relatively speaking, it doesn't seem like there are many good Prince tabs out there. Thanks in advance. Mahalo. [Edited 8/3/09 9:11am] You may be talking about the issue from 1999. It has his set up in this issue. Several good pics from the past eras up to the rave era. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable