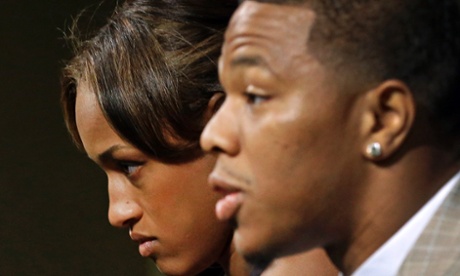

Early Monday morning, TMZ released a “cleaned up” video of Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice beating Janay Palmer, his then-fiancée and current wife, in the elevator of an Atlantic City casino. The footage shows Rice, the 206lb (95kg) NFL star, delivering a blow to Palmer that slams her against the elevator railing – that knocks her unconscious. He then drags her body, limp and unresponsive, out of the elevator with a shocking lack of apparent concern.

After investigating the accusations against Rice – to which the Baltimore Ravens running back pleaded not guilty and en...on program for first-time offenders to avoid a trial – NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell handed him a paltry two-game suspension in July. Thousands of people, far and wide, called into question the ...s judgment for such a featherweight punishment of an act so violent.

Now, within a matter of hours following the release of the tape, as those questions ratcheted up, the Ravens have terminated Rice’s contract. Strangely but not surprisingly, scrutiny has also increased around the woman’s behavior – the woman who, by the looks of that very tape, was brutalized.

That we feel entitled (and excited) to access gut-wrenching images of a woman being abused – to be entranced by the looks of domestic violence – speaks volumes not only about the man who battered her, but also about we who gaze in parasitic rapture. We click and consume, comment and carry on. What are we saying about ourselves when we place (black) women’s pain under a microscope only to better consume the full kaleidoscope of their suffering?

This broadcasting of victims’ most vulnerable moments as sites for public commentary is not new. Indeed, victims of abuse have always been forced to recount their traumas to audiences more intent on policing their victimhood than finding justice. With YouTube and TMZ and all the rest, victim blaming extends far past simply being shunned by your immediate community – it means having your most horrific memories go viral without your consent. It means having millions of people virtually dissect your wounds, not to heal them but to decide if your injuries were bad enough for everyone to feel bad for you.

Black women are often systematically excluded from both the category of “woman” and that of “victim”. Our pain, these days as ever, can never be pure enough.

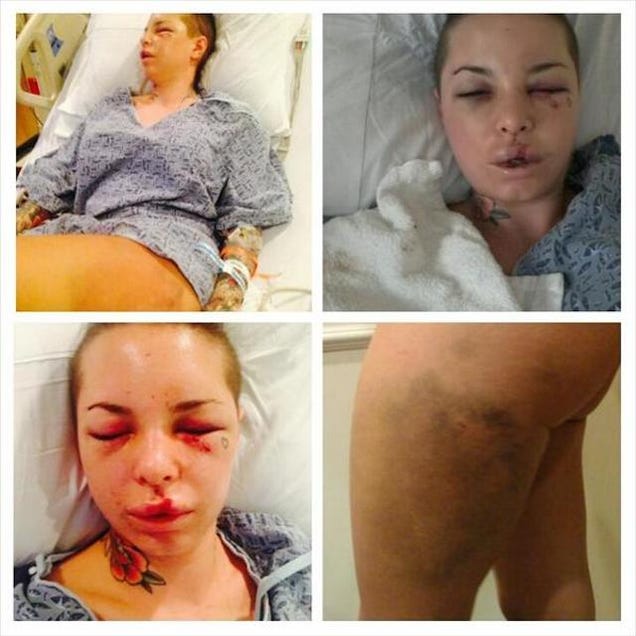

When Chris Brown assaulted Rihanna in 2009, images of her bruised face surfaced and spread across the web. Despite the female pop star’s wishes that the photos not be publicized, they were used by everyone from feminist advocates trying to make a point about Brown’s violence to someone promoting the male pop st... in Sweden. People couldn’t turn away; there was something addictive about her visible agony, both as misery porn and an all-purpose rhetorical tool.

We viciously ingest every vivid detail of women’s victimization, line our stomachs with their blood and tell ourselves we’re watching because we want people to be “educated”. If only people could see enough black eyes, bloodied faces and broken ribs, the theory goes. Then they would know the truth, we tell ourselves. Only then would they care.

But that deluded fetishization is every bit as untrue as it is exploitative. In reproducing victims’ trauma over and over, we only expose them to more harm. Throughout this six-week public ordeal, Janay Palmer’s pain has been minimalized, her judgment called into question. “Why did she marry him after he beat her?” reverberates around the web and in our minds, an accusation masquerading as a concern. When victims reveal their experiences (or have their experiences revealed by someone else), viewers reach for pre-packaged answers, rather than listen to victims themselves.

It is easier to believe that a woman “provoked” catastrophic violence from a supposedly otherwise peaceful man than it is to come to terms with the fact that a well-liked public figure is abusive. It is easier to conceive Palmer as an accomplice in her own beating than it is to realize that almost half of black women killed by their partners were killed as they tried to leave.

The official Baltimore Ravens account tweeted this earlier in the summer:

That is evidence of how far we will go to avoid demanding accountability from perpetrators as we continue to watch their victims bleed for us. That is the most perverse of pleasures, the hollow indulgence of someone else’s pain. We are wedded to our own numbing ignorance, to the slow venom that silences victims and emboldens abusers. It is comforting to think you could never be a victim, that you are better or smarter or more innocent than that wayward woman who “should’ve known”.

But in a world in which one in four women is the victim of intimate partner violence and black women are disproportionately targeted, this victim blaming is not just irresponsible; it is lethal. Black women are punished when attempting to defend themselves: 94% of black female homicide victims are killed by people they know and 64% of those victims are wives, ex-wives or girlfriends of their killers. Who will support victims when abuse is not recorded and pre-packaged solely for our consumption but subtle and drawn out, or when the state itself commits violence?

If we viewed victims as more than a link to be tweeted, more than statistics to be reported to a broken criminal justice system, we would have to grapple with their complex humanity. We would have to offer meaningful solutions to violence, holistic responses to trauma, and accountability for abusers whom we may love. We would have to do more than just watch.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/sep/08/ray-rice-domestic-violence-video-janay-palmer-victim-blaming

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator is she so desparate for the $$$$good life?

is she so desparate for the $$$$good life?