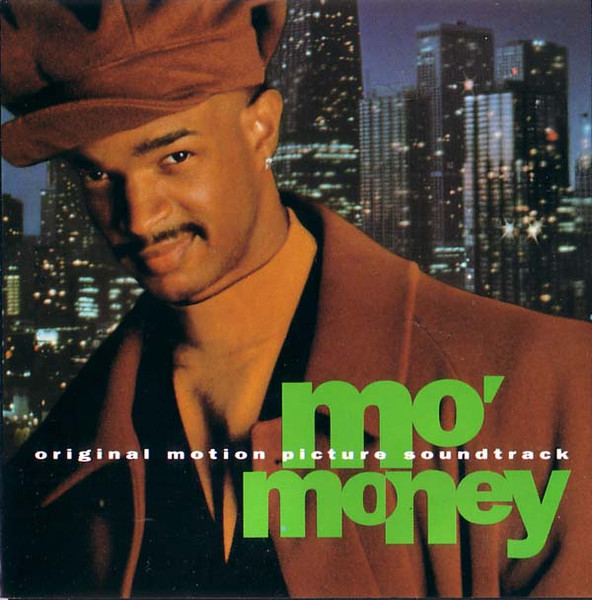

Happy 30th Anniversary to the Mo’ Money Soundtrack, originally released June 23, 1992.

It’s easy to find big screen films with Black personnel in front of and behind the camera now. But 30 years ago, that was hard to come by. So every Black film was a big event. The early ‘90s brought a renaissance for this kind of cinema and another one had made it from concept to completion: Mo’ Money. When Damon Wayans wrote the 1992 comedy and needed a soundtrack, he reached out to “Jimmy and Terry. Why? Because they’re the best. They’re hitmakers.”

Following a curt 1983 dismissal from Minneapolis funk band The Time, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis were expected to hit the skids. Instead, their Flyte Tyme Productions collective hit the charts making millions with Janet Jackson, New Edition, The Human League, The S.O.S. Band, Alexander O’Neal, Cherrelle, and more.

In 1991, they minted their own label Perspective Records and launched several artists successfully before Wayans came calling. Wayans partnering with Perspective meant guaranteed hits. Hits mean a cross-promotion for the film. Box office success meant promotion for the label. As In Living Color‘s Homeboy Shopping Network hosts would say, “Boom… Mo’ money! Mo’ money! Mo’ money!”

The film based on this and other skits from the sketch comedy show stars brothers Damon & Marlon Wayans. On screen, they play freewheeling siblings Johnny and Seymour who run petty scams as a way of life—until Johnny meets Amber (Stacey Dash) and feels poverty is coming between him and the love of a beautiful woman.

This premise inspired Mo’ Money‘s R&B #1 lead single “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” a high-octane duet with consummate balladeer Luther Vandross and pop-soul princess Janet Jackson. Though their styles are worlds apart, it was his idea to play against type stepping into her lane. Their sweet and savory voices emulsify on a rambunctious track that combines BBD’s “Poison” with George McCrae’s “I Get Lifted” bassline to create a single as novel as it is essential. Adding to the aggregate is two-thirds of BBD rapping (“Biv DeVoe! Here we go!”) with fellow New Edition alum Ralph Tresvant. Luther gets the last word though, scooping a final “yeah” with his honeyed baritone.

When that “cassingle” dropped May 12, 1992, I had to grab it. Jam & Lewis always deliver, but that tape’s snippets really hooked me. One verse and chorus each from Tresvant’s “Money Can’t Buy You Love,” Johnny Gill’s “Let’s Just Run Away,” and KRUSH’s “Let’s Get Together (So Groovy Now)” and my bell was rung. The wait for the full soundtrack in June felt like an eternity.

Soon, the lushly arranged “Money Can’t Buy You Love” was serviced as a second single. It was so satisfying, any edit short of its full six minutes felt unjust. Like Tresvant’s Flyte Tyme-crafted #1 “Sensitivity,” this continues the established Marvin Gaye-meets-New Jack Swing motif. The single’s healthy R&B chart run topped out at #2. This album was about to be something special.

More than mere background, Mo’ Money is an audio snapshot of Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis developing the sound that would shape ‘90s R&B and pop, and having fun doing it. This is evident with the opening pep rally “Mo’ Money Groove.” The loose and lengthy all-star overture is packed with hype, hip-hop chants, and the blaring fanfare of Lyn Collins’ “You Can't Love Me if You Don't Respect Me.” Mo’ Money wouldn’t just collect substandard, tossed-off miscellany. It came packed with bespoke material—often written for specific scenes.

In the film, Johnny propositions Amber (“I wish I had an ice cream / that looked just like you / sweet tasting chocolate / all the way through / I’d lick you slow from head to toe”). MC Lyte spins this semi-limerick into the Top 20 single “Ice Cream Dream.” Full of flavor from EPMD’s “So What Cha Sayin’,” it allows Lyte to toy with innuendo (“Drip drop / Come on / Feed me, Seymour!”) without sacrificing femininity or swagger.

Hip-hop is well represented on Mo’ Money. Beyond Lyte and BBD, Flavor Flav also takes center stage on Public Enemy’s “Get Off My Back.” Big Daddy Kane’s inherently comical “A Job Ain’t Nuthin’ But Work” subverts his “I Get the Job Done” persona to embody Seymour’s character (“I’m so against workin’ / I wouldn’t even take a blow job”). It doesn’t stop there as Perspective signees Ann Nesby and Lo-Key? set flames to the chorus with sweaty gospel-funk. (Incidentally Lance Alexander and Tony “Prof T” Tolbert of Lo-Key? are sometimes credited with Jam & Lewis as “The Flow” and contribute significantly as writers and producers.)

On the lighter side, Mo’ Money test drives new group KRUSH. These flowerchild fly girls land somewhere between TLC and The Good Girls. Their ‘60s mining “Let’s Get Together (So Groovy Now)” puts rapid rap verses on display and decorates them the best highlights of Friend & Lover’s “Reach Out of the Darkness.”

Jam & Lewis also seized a moment to work with Afrocentric UK singer Caron Wheeler on “I Adore You.” The track liberally drapes her zesty adlib from Soul II Soul’s “Back To Life” around, but the chorus isn’t Wheeler at all. It’s a clever snip of “Don’t Make Me Over” by Sybil. The well-received #12 R&B single gave extra mainstream R&B kick to Wheeler’s Beach of the War Goddess (1993).

For being so front loaded with high-energy party music, Mo’ Money also has some potent headboard knockers on it. For one, Mint Condition turns in the Prince-drenched “My Dear” that takes its time building intensity. Johnny Gill slides in the steamy slow jam “Let’s Just Run Away” based on a moody George Duke deep cut from 1974 called “Feel.” This sensuous exhibition reached #56 on the R&B charts even without being released as a single.

The most important track here is perhaps its most unassuming: Jam & Lewis’ own “The New Style.” Its vocals come from an unfinished Jackson recording called “Beat Crazy.” Portions of her harmonizing “control my mind” float around a galvanizing fusion of freestyle dance beats, hip-hop swing, and pop chord washes. The lavish way they embrace sampling here and throughout Mo’ Money is a paradigm shift in the Flyte Tyme sound that would reach fruition on janet. (1993) continuing forward. They have an innate ability to adapt for their artists and find connections between their sound and the culture at large. That is what makes them superproducers.

The platinum-certified soundtrack charted #2 R&B and #6 Pop. Released only one week after Mo’ Money was some stiff competition: Babyface & L.A. Reid’s Boomerang soundtrack. Boomerang took residency at #1, staying on the chart for two months. While both were artistic peaks and cultural touchstones that evolved the viability of Black music in America, only timing and opportunity kept the underrated, but overqualified Mo’ Money from touching the top spot that summer.

That wouldn’t be their last go at it by far. The next decade brought huge hits like Boyz II Men’s “On Bended Knee,” Mary J. Blige’s “Everything,” the whole of Janet Jackson’s discography during this most fruitful period and significant work with her brother Michael on HIStory (1995) and Blood on the Dance Floor (1997), more collaborations, more soundtracks, and more evolutions. And yet one can still draw lines to connect those evolutions back to this one summer soundtrack in 1992 that served as a midpoint of their metamorphosis. It’s been here the whole time, ripe for rediscovery.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator