| Author | Message |

Country & Western Early Country Music: Hillbilly Records

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

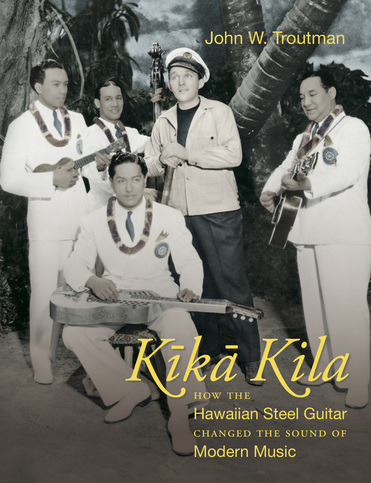

From Honolulu To Nashville: Hawaiian Music and Country Sol Hoopii (1943) King Benny Nawahi ~ Black Boy Blues Kalama's Quartet ~ Kawika / Liliu E Joseph Kekuku And The Steel Guitar Heart Strings: The Story ... ʻUkulele Uncle Willie K And The Hi...An Ukulele Sol K. Bright & His Hollywaiians ~ Heat Waves (1935) Andy Iona And His Islanders (1939) Hal Aloma ~ Holo Holo Haa (1949) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Samantha Bumgarner: Fiddling Ballad Woman Of The Mountains The Original Banjo Pickin’ Girl You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

those are some scary looking people.... | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I will listen to some of the music. It is good to be a "student" of diverse music genres! [Edited 10/9/20 22:55pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Very interesting reads. I love the old country music. Are all these excerpts from American Popular Music: From Minstrelsy to MP3? Seems like a book I should get my hands on. It was not in vain...it was in Minneapolis! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Audrey Winters, Little Richard, Tammy Wynette, George Jones

Around 1972 Little Richard recorded an album called Southern Child. It wasn't released at the time, but the songs from it were eventually released on a CD box set in 2005. Richard also recorded a duet with Tanya Tucker called Somethin' Else on the 1994 various artists album Rhythm Country And Blues. Here's some songs: Somethin' Else - 1994 Country Music Awards One Day At A Time - Late Night With David Letterman 1982 In The Name (version 2) In The Name (version 3) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

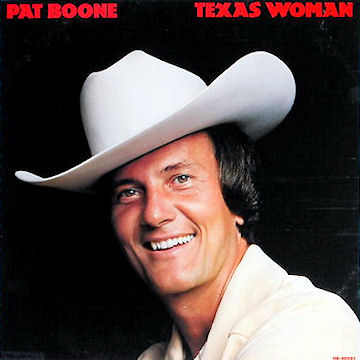

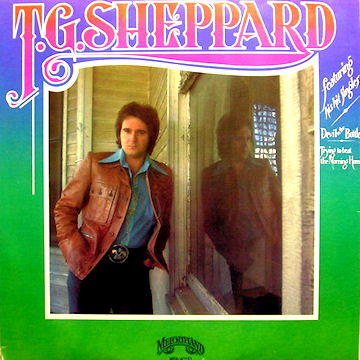

Melodyland/Hitsville You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

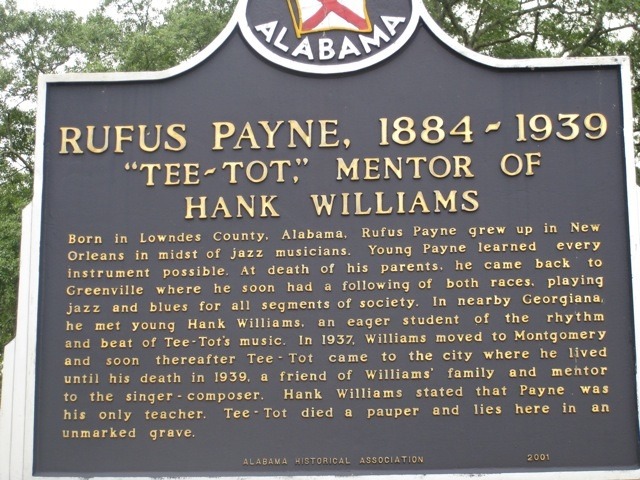

Rufus "Tee Tot" Payne (1884 - 1939) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Kika Kila: How The Hawaiian Steel Guitar Changed The Sound Of Modern Music You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

The Banjo: America's African Instrument Faculty Bookwatch: Laurent Dubois Rhiannon Giddens: The Los...lack Banjo You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Arnold Shultz (1886–1931) Bluegrass Today Dr. Richard Brown on Arnold Shultz You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Linda Martell Ebony (March 1970) Rolling Stone (September 2020) Bad Case Of The Blues (Hee Haw 1970) San Francisco Is A Lonely Town Before The Next Teardrop Falls Linda Martell And The Anglos ~ The Things I Do For You You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

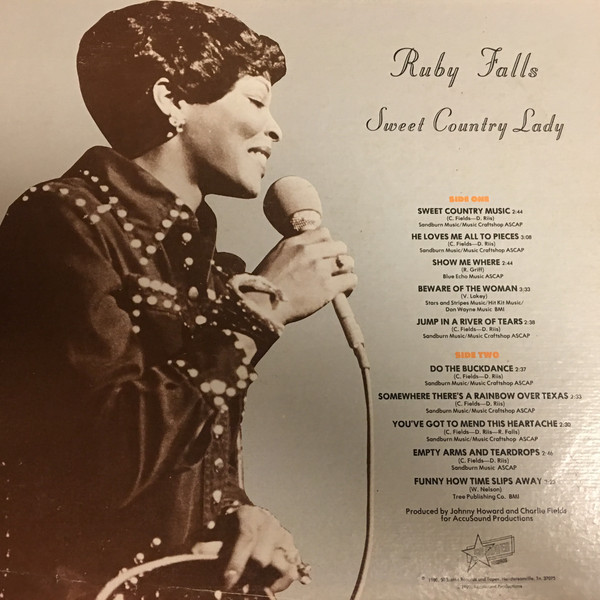

Ruby Falls (January 16, 1946 - June 15, 1986) The Black Women of Country Music

He Loves Me All To Pieces (1975) Let's Spend Summer In The Country (1975) Somewhere There’s A Rainbow Over Texas (1976) Beware Of The Woman (Before She Gets To Your Man) (1976) You’ve Got To Mend This Heartache (1977) Do The Buck Dance (1977) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Great topic MD! I need to read these this week. I’m hoping the re-air the PBS country series I missed it. Just Music-No Categories-Enjoy It! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Pressing On: The Roni Stoneman Story (2007) The Stonemans ~ Donna-Mite(The Road To Nashville 1967) The Stonemans ~ White Lightning / Mountain Dew Stringbean, Grandpa Jones, Roni Stoneman, Roy Clark, Bobby Thompson ~ Stop That Tickling Me Roni Stoneman & Roy Clark ~ Roy / You Can't Take Country From Me You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Sun, sea and stetsons: why St Lucia loves country and western musicby Alexis Petridis • August 10, 2014

St Lucia's homegrown country star LM Stone plays to the faithful, filmed for the documentary Make Mine Country. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Garth Brooks Hints That We Haven't Seen The Last Of Chris Gaines You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Hidden In The Mix: The African American Presence In Country Music (2013) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Country Soul: Making Music And Making Race In The American South (2015) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Never Look At The Empty Seats: A Memoir (2017) James Brown & Charlie Daniels ~ Papa's Got A Brand New Bag / I Got You Daddy's Old Fiddle (with Dolly Parton) The Devil Went Down To Ge...Simple Man (Arsenio Hall Show) Charlie Daniels, Roy Clark, Ricky Skaggs ~ Roy Acuff tribute You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Wow, thanks. You seem to be a music historian...love it. Didn't Elvis mix Hillbilly, Country and Blues? | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Elvis, another Capricorn! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

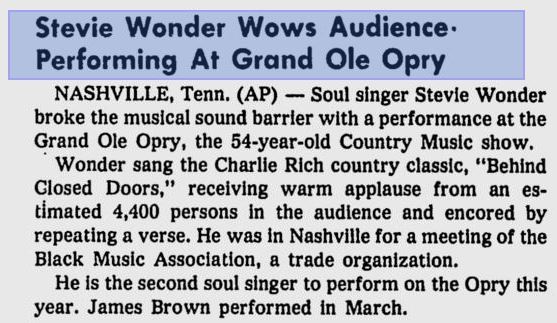

Ocala Star-Banner • September 9, 1979

Stevie ~ I love from bluegrass to LA music to country. I love music, period. What I can tell you is that I have always been a lover of music and country music. Signed, Sealed, Delivered (2007) Harpejji Medley (2015) Johnny Cash & Stevie Wonder Get Rhythm John Denver ~ If Ever (Stevie on harmonica) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Gospel too. Mavis Staples mentioned in her autobiography that Elvis used to come to her church. Elvis background singers The Jordanaires was a gospel group. Elvis & Conway Twitty used to chart on the R&B chart in the 1950s. Conway Twitty & Ronnie Milsap first started out as R&B singers before switching to country. In the 1970s, Barbara Mandrell had R&B elements in some of her songs too. It was common for R&B/soul acts to remake country songs and vice versa and some session musicians played on records in both genres. Joe Tex had a country music producer and Nashville session guys on a lot of his albums. Stax Records was originally a country music label and that vibe remained after changing to primarily R&B: "Otis you country, straight from the Georgia woods!". You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

[Edited 10/15/20 19:03pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

How could I forget Gospel (Elvis) I also heard that Elvis and his GF would sneak out of their church and head for the black church (then sneak back in time) Goes to show that 'genres' are intertwined. I bet you have a fabulous album collection!

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Hee Haw (1969-1997) You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

My play auntie loved country music, unfortunately she lived in a conflict with it. Anyway I think it was thru her I at least have an appreciation for it, it's pleasant to my ears. Time keeps on slipping into the future...

This moment is all there is... | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I've always enjoyed the harmonies in Country music...used to love Don Williams. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable