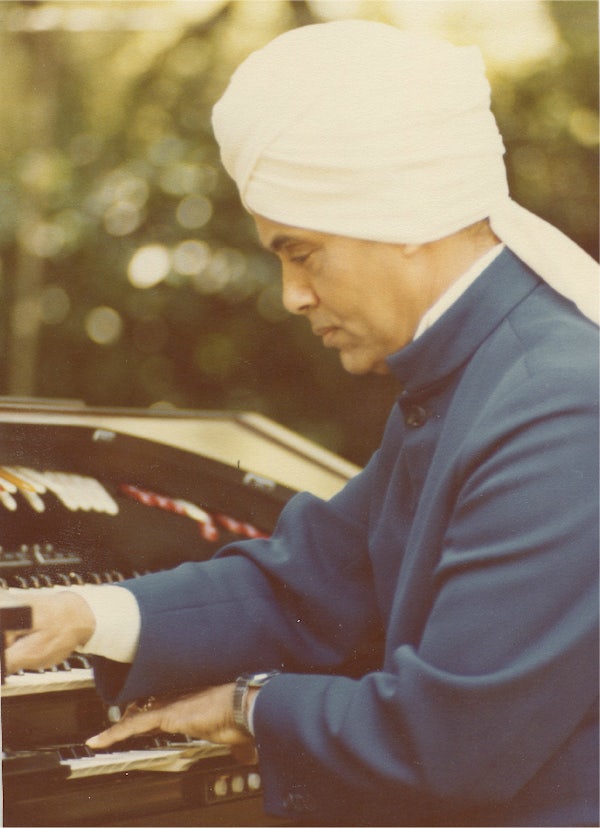

Before Liberace, there was Korla Pandit. He was a pianist from New Delhi, India, and dazzled national audiences in the 1950s with his unique keyboard skills and exotic compositions on the Hammond B3 organ. He appeared on Los Angeles local television in 900 episodes of his show, “Korla Pandit’s Adventures in Music”, smartly dressed in a suit and tie or silk brocade Nehru jacket and cloaked in a turban adorned with a single shimmering jewel. The mysterious, spiritual Indian man with a hypnotic gaze and sly grin was transfixing.

Like most everything in Hollywood, it was all smoke and mirrors. His charade wasn’t his stage name—it was his race. Korla Pandit, born John Roland Redd, was a light skinned black man from St. Louis, Missouri. It was a secret he kept until the day he died.

A new documentary, Korla, explores Pandit’s extraordinary life and career. Filmmakers John Turner and Eric Christiansen grew up in the Bay Area watching Korla on TV and listening to his music. The two worked together for 35 years at KGO-TV in San Francisco, where Korla had a live show in 1964. Both fell under his spell learning the truth in a Los Angeles Magazine exposé in 2001, three years after Pandit’s death. “He was a slight man with a beatific smile who was spouting pearls of wisdom about how we could get along better and the universal language of music,” Turner told me. “Why question a person like that?”

.

As legend has it, Korla was a child prodigy born in New Delhi to a Brahmin priest and a French opera singer. When he was 11, Korla was sent away to England and then to America for classical training at the University of Chicago.

.

Pandit’s invented life closely mirrored his real one. John Roland Redd was one of seven children born into a musical family. His spirituality can be traced to his father, a Baptist minister. His mother was of Creole ancestry. Most importantly, his talent was real. Relatives interviewed recall that, at age three, John could learn a song once and have it memorized.

“It’s the definition of a myth,” said record producer Brian Kehew, who worked with Korla in the mid-1990s. “The reason his story rings true is there’s truth in it. I never questioned the concept. He looked like an old Indian man,” Kehew continued. He was one of few people who managed to catch a glimpse of his straight, jet-black hair free of its turban.

Americans fascinated with the east eagerly accepted this charming figure and his mystical interpretations due to their minimal knowledge of the Indian culture and customs—by and large, Americans were only exposed to swami stereotypes in TV and film. Which is probably why nobody disputed his fantastic story, although he was notably uncomfortable when Indian fans asked to meet him after his gigs. “He wasn’t the first person to pass as a white man in order to get ahead, he just passed as an Indian man wearing a turban,” a childhood friend remarks in the film. (Christiansen: “In hindsight, he said he was Hindu but Hindus don’t wear turbans. Sikhs do, but they don’t wear jewels on their turban.”)

.

It wasn’t the first time Redd had passed as something other than black—Korla Pandit was just one of his incarnations. After arriving in Los Angeles, he began playing jazz and R&B but quickly realized he could make more money playing Latin tunes as “Juan Rolando”. Passing as Mexican, he was able to join the whites-only Musicians Union. Soon he was playing supper clubs and lounges, on top of a gig providing eerie background music for the “Chandu the Magician,” occult radio show. As “Cactus Pandit” he played for Roy Rogers’ cowboy singing group, “Sons of the Pioneers.” In Korla Pandit, though, Redd had found a winning formula. He took the organ, an unpopular instrument associated with soap operas and roller skating rinks, and made it sexy and magical.

.

“I really think he really became that person,” Christiansen said of his transformation. “He was more Korla Pandit than John Roland Redd. His makeover into Korla informed his music, not the other way around.” His wife, Disney animator Beryl June DeBeenson, was the architect behind his mystique and final metamorphosis. In 1948, the couple met the television producer Klaus Landsberg at Tom Brenenman's Restaurant; he offered Korla the daily TV show that would make him famous. Pandit had only two requirements: First, that he’d provide music for the “Time for Beany” puppet show; and second, that he would not speak on camera.

.

“I think they both recognized that becoming Korla Pandit was an opportunity for him to gain a level of fame that he couldn’t have as a black man,” said Allyson Hobbs, assistant professor of history at Stanford University and author of A Chosen Exile, an examination of racial passing in America.

In 1951 Pandit signed with Louis Snader, a California theater owner and TV producer, whose telescriptions—short film clips used as fillers on local stations across the country—gave Pandit national exposure. After a contract dispute in 1953, Snader replaced him with another eccentric pianist who also had a secret: Liberace. “[Liberace] used the same sets and took credit for his staring into the camera and breaking that wall," said Christiansen. “He felt like Liberace stole his soul.”

.

Five years later, in 1956, Korla Pandit went north to San Francisco for another show. During this time, he also recorded 13 albums for Fantasy Records, whose roster included Chet Baker, Dave Brubeck, and Lenny Bruce. “What he was doing in terms of reinventing himself wasn’t that unusual by Hollywood or music industry standards,” Turner said. It was a time when anyone could become anybody.

“Korla’s story shows us just how fluid identity was in the 1950s,” Hobbs said. “Often people passed for survival doing things they couldn’t if they were living as black person. In doing that they lost a lot. They had to separate from family to fully inhabit a new life.” Redd’s family had a different understanding of the pressures of passing, however. “They felt he was very authentic and were very close to him,” Hobbs said after meeting family members at a recent screening in San Francisco.

.

As Korla’s career waned in the ’60s, he was relegated to playing supermarkets and pizza palaces, teaching piano, and occasionally attending speaking engagements as a spiritualist. In the ’90s, near the end of his life, the Tiki-lounge music revival gave Korla one last career resurgence and cult following. He recorded with The Muffs, and made a cameo appearance in Ed Wood. One of his last performances was a sold out show at the legendary Bimbo's 365 Club in San Francisco.

“In my mind the movie is not about Korla’s false story or deception,” Kehew said. “That doesn’t matter to me compared to how good he was musically. If you want to be up on the stage in a spot light you have to be more interesting than the person on the street,” he continued. “That’s what Korla managed to do.”

.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator