OVER THE COURSE of her 17-year career, Jane Monheit has established herself as a dynamic and expressive vocalist. Raised by music-minded parents — her mother was a singer; her father played banjo and guitar — Monheit grew up in Oakdale, New York (on Long Island), listening to a variety of music, connecting particularly to jazz and Broadway musical theater. While attending the Manhattan School of Music, where she graduated with honors in Voice, she was the first runner-up in the 1998 Thelonious Monk Institute’s vocal competition. By 2000, the then 22-year-old singer had released her first album, Never Never Land, on New York’s N-Coded Music label. Critics responded with near-unanimous praise. Said AllMusic’s David Adler: “Her voice is about as close to flawless as a human can get, yet she’s never coldly technical or aloof.” She quickly developed a loyal fan base of music lovers enamored as much by her voice as by her sultry onstage persona as “a glamorous broad,” Monheit has said of herself, matter-of-factly.

Since then, Monheit released nine chart-topping albums with five different record labels, spending much of her time fighting for creative control of her music from tone-deaf decision makers who cared less about developing her artistry than profiting from her image. Following her 2013 recording, The Heart of the Matter, Monheit launched the Emerald City Records label, and her latest, The Songbook Sessions: Ella Fitzgerald, is the first release from that imprint. The album is an homage to an artist Monheit describes as a “beautiful, warm, and loving presence,” and a proclamation of Monheit’s own musical independence.

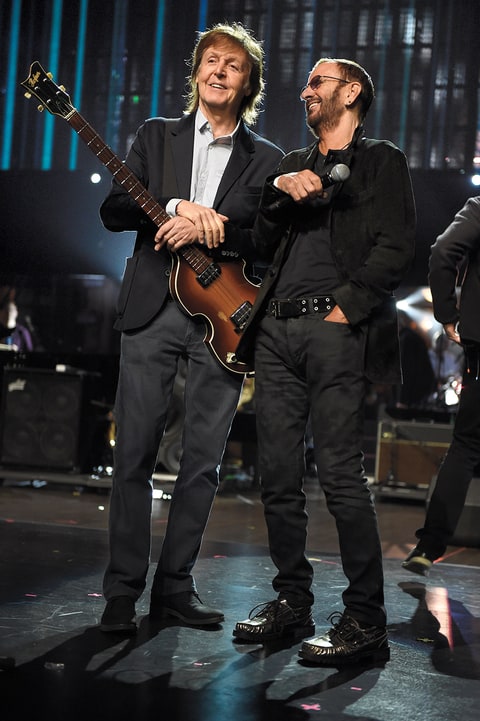

On Songbook Sessions, Monheit rips up the standards’ playbook she’s followed for much of her career. Monheit, like Fitzgerald before her, became widely respected for traditional interpretations of the Great American Songbook, the canon of American pop songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century — the same songs she grew up listening to as a child — and straight-ahead jazz renditions of tunes by Paul Simon, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Fiona Apple. With this new work, Monheit recasts a dozen well-known standards with her unique stamp. In collaboration with trumpeter Nicholas Payton and her longtime trio — which includes pianist Michael Kanan, bassist Neal Miner, and drummer Rick Montalbano (her husband) — Monheit delivers a songbook that bespeaks the adventurous, transformative rhythms of a 21st-century artist, with the emotional depth and range that is emblematic of the First Lady of Song. Even Monheit, listening back to takes from the album, says she could hear “a different singer than I’ve heard before” — the deeper, richer tones of “a 38-year-old woman with a lot of life experience.”

During the making of the album, Monheit went through what she refers to as her own personal hell. She was sick with bronchitis for five of her studio sessions, her dog was hospitalized, and her 94-year-old grandfather, with whom she’d spend so many of her childhood hours with listening to records and singing duets, had died. In the midst of her mourning, Monheit, who lives in Rome, New York, with her husband and son, Jack, was four months pregnant. She suffered a miscarriage with a little boy.

“Someday maybe she’ll write in her autobiography about all of the loss she suffered in the weeks leading up to the making of this album,” Payton wrote in the album’s liner notes.

During our conversation, however, Monheit is upbeat. She laughs a lot, has a wise guy sense of humor. Despite the personal pain, it has led her to a new place, as a woman and an artist — and she’s excited about the new singer she’s become.

¤

CHRIS BECKER: Ella Fitzgerald was so many things to so many people. Tell me who she was to you.

JANE MONHEIT: She was one of the true originators of the art form. She was one of the first singers to really take the influence of the instrumentalists around her and bring them into her singing. But more importantly, in addition to all of the technical things she did as a singer — the swinging, the scatting, and all of that — she sang with such great warmth. I know a lot of people who knew and worked with Ella, and they all say she was like that in person.

When were you first introduced to her music?

I was at home with my mom. My mother was a singer and because I loved to sing, she was very conscious of playing singers for me that I could learn from. Little kids tend to copy. She knew I was going to be singing along with records and wanted to make sure they were singers with good technique. I remember her putting on Ella for me, and saying to me, “Listen to this!” and me just losing my little mind over how beautiful it was.

Was it just the sound of her voice that moved you?

Yes! I remember that specifically, the sound of her voice.

You have described Ella’s songbook albums as “biblical.” Why are those particular albums so important to you?

As a child, they were what I chose to focus on. I don’t know why. The songbook albums are more of the pop music of their time. She’s not doing a ton of improvisation, so they were wonderful records to learn these songs from. But Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Song Book, which is by far much more of a jazz record than the other ones, has always been my favorite. She’s looser on that record, and she’s singing more jazz.

In Ella’s later recordings, one hears so much joy in her singing, but there’s also wisdom, and even some sadness in the material as well. Could you connect to that?

Ella was someone who was able to sing with complete and utter sincerity, but without any histrionics. That’s a place I need to get to! [Laughs.] She was a total sage. That’s the mark of any great singer, to be able to distill life experiences into a song and help people understand other people’s experiences. Ella was brilliant at that, but she did it in such a calm, collected way. That’s something I do not know how to do. For all of her influence on me, I sing in this crazy emotional way. Ella was able to sing something so calmly, and you would believe her. I can’t do that yet.

Quincy Jones has spoken about the “open wound” that pushed Ella, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, and other singers to greatness. Is that what you’re talking about as well? Having those painful experiences and then being able to speak about and share them through singing?

You want to use your experience to help provide some catharsis for others. But I think it’s the same with your joyful experiences. It doesn’t have to be just the things that hurt us. As a singer, you get used to having your heart on your sleeve. It’s about accessing all of it, and having it at the ready. I always tell my husband, if I’m being overly emotional or overly dramatic, “No, no, no. This is cool. It makes me good at my job.” [Laughs.]

Ella was very inspired by instrumentalists of her time, but can singers influence instrumentalists as well?

They should. Here’s the thing, these songs we’re talking about, songs from the Great American Songbook — the music and lyrics were written at the same time by these incredible teams of writers. So the lyrics are just as integral to the composition as the melody, and when you have the singer’s interpretation there’s another layer there. Hopefully, a horn player will hear that, and want to express some of that lyric in the way they approach playing the tune. [Saxophonist] Ben Webster said he wouldn’t play a tune unless he knew the lyric. I love that.

So let’s talk about the new album: what inspired you to frame your rendition of Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood” with Billy Strayhorn’s “Chelsea Bridge”?

I love medleys, and mash-ups, when you take two songs, put them together, and expand the story. I create stories in my head when I’m interpreting these tunes. With “Chelsea Bridge,” that’s the present, sung by someone who is going into a memory, and then arriving at that memory with “In a Sentimental Mood.” Generally, jazz singers sing songs in lower keys, more where we speak. But I chose to put “In a Sentimental Mood” in a high key so it would feel innocent and virginal, like the first experience with being in love. Then we come back to the present, where “Chelsea Bridge” is singing through this memory.

Your version of “Ill Wind” is very powerful, and Nicholas Payton’s arrangement of it is quite emotional.

It was a very dark time for me, and Nick knew that. Nick is a good friend. The whole treatment of that song had very much to do with what my life was like at that moment. I have this imagery in my head of the story I’m telling with that song. The percussion sounds sort of outdoorsy, like a hot summer night. You can sort of feel the unease, like a storm is coming. I pictured this woman, and her children are asleep, they’re fed, they’re safe. She didn’t eat so she could feed them, and she knows that this man is out there, and he’s coming for her, and she doesn’t know when. But at the same time, I was singing about what I was going through.

Last fall was an ugly time. I went through a lot of loss, all at once, and it was difficult. It’s never easy for anybody, but it was the first time in my life that I had ever truly, truly experienced the full misery of loss. I had been very, very lucky, and not really gone through that. But last fall, I sure did, and I did hard.

And Payton used that to push you. He writes in the album’s liner notes that as the producer, he wanted to make you feel comfortable, but also slightly uncomfortable, toward “some paths less charted.” What were some of those paths he took you on?

The arrangements. I’m a real traditionalist. When you go back and listen to my recordings, it’s very much, “This is what the composer intended …” And I love doing that, I love honoring the history. But Nick really wanted to get me outside of that and try some other things.

I was absolutely thrilled with the arrangements. At first, they were a little scary to me — like, can I get away with this? But then I thought, wait a minute, what the hell am I worried about? I’m 38 years old, I can do whatever I want, and I’m gonna love it. [Laughs.] And I did! I trusted Nick completely, and went into the record with no fear.

There’s a seamless blend between Payton’s trumpet solos and your voice. I imagine that as a singer that was really great to hear.

[Joking] Oh, man, are you kidding me? There’s nothing worse, nothing worse than you’re singing a tune, you set up a mood, you create a scene in everyone’s heads, and then a soloist comes in and just dashes it to pieces. It’s like, you’re playing your ballad, and it’s so beautiful, and here comes the solo and the rhythm section in double time and we’re all freaking cheerful! No thank you!

But seriously … For Nick to solo with me, and to extend the mood I’m trying to create so it’s something we’re building together, especially on “Ill Wind” or “Chelsea Mood,” that’s total magic. That’s what the greatest soloists do. They play with you. They don’t compete.

When listening back to the takes, you said you “heard a different singer than what you’ve heard before.” What do you mean by that?

In September and October, I aged very drastically. I went through a lot, and it changed me completely as a person. So then you sing, and the differences show. If you’re doing your job right, they show.

I didn’t want to comb through and fix all the vocals and make them perfect. I just let everything be what it was. For me, it’s so much more about capturing the performance than capturing a technically perfect vocal. I think if you’re spending too much time worrying about being perfect, maybe jazz isn’t the genre for you. We’re here for truth, not for perfection.

The Songbook Sessions is your first release on your Emerald City Records label. Why did you decide to start your own label?

I had been with five different major record labels in 15 years. That’s a lot, and I was never really truly happy with the way things worked anywhere. When I was young, I had a lot of artistic control. But as I got older, it became harder. People wanted to take that control away and see what they could turn me into.

Then there’s the whole image thing. You know how tired I got of picking up an album and seeing someone Photoshopped into oblivion; someone who doesn’t even look like me? I mean, come on! I enjoy the glamour and the makeup and the hair and the dresses and the jewelry and the whole thing. I love that stuff. But get away from me with your damn Photoshop! [Laughs.] I’m a human being. I’m not here to be jazz Barbie! And when you make however many albums, and never see a dime? That gets old too.

Of course, now that you own the product, its success and failure is all on you …

No one is going to let you down, except yourself. I’d rather be in that position.

Then are you having to consider what your fans may want to hear?

It is a consideration. However, if you come to one of my shows, you’ll see children my son’s age, and their grandparents are there too. Maybe great-grandparents! You’ll see all different kinds of people, all walks of life. I love it that way. It allows me a lot of freedom as an artist, because no matter what I do, there’s going to be somebody who appreciates it.

We’re not really in it for the money, because there isn’t any. [Laughs.] There really isn’t any. Some people think I’m rich and famous. I’m so not. I’m very likely to be doing a show in a dress I got at Target. It is what it is. We play this music because we love it.

But now that I have my own label, the record sales matter. The other day I did a show where I had people in the audience filming the show. One guy even had a laptop open. In between songs I said, “Look. I get it. But here’s the thing: I’m my own label now. So if you make your own record, and don’t buy mine, you are literally taking money out of my pocket. So please put your phones away. You can’t hurt Sony or Universal that way, but you can hurt me.”

When you ask them to, do people put their phones away?

The cool ones do.

This is something the younger jazz singers are going to face more and more. Are their other challenges that are unique to their generation?

If anything, the challenge is we now live in a culture where every last person thinks they get to be a star. It used to be you had to luck out. You had to be chosen. A record company had to want to sign you, a manager had to want to manage you. You became a part of the show business machine because you were ready when it came. That magical combination of luck and readiness. It’s not like that anymore, and it’s a shame. The market is overstuffed.

Does it make it harder, then, for younger artists to handle criticism?

That depends on the person. There is an overwhelming vibe of no one has to pay any dues anymore. I was on the last run of that. I studied this music my whole life, sang thousands of non-paying, little gigs where I was learning nonstop on the bandstand. I got my ass kicked by the elder statesmen of this music, learned frantically, and then got my opportunity and was ready — as ready as I could be at 20 years old.

Are there still venues for younger singers to get up on the bandstand and learn and pay their dues?

Yes, but not as many as there were when I was coming up. It also comes down to creating opportunities for yourself. If there isn’t a jam session in your town, call up some musicians and have a session, you know? You need to actively and repeatedly get your ass kicked by musicians who are better and stronger and wiser than you. It’s just an essential part of growing for a young musician.

Does that have to happen outside of an academic environment?

I don’t think it matters. I was lucky. At the Manhattan School of Music, I was surrounded by musicians who knew much more than I did. So not only was I learning from my teachers, I was learning from my friends. I definitely got a fancy conservatory education, but I learned just as much on the bandstand as I did in the classroom. It’s the combination of those two things that has made me who I am.

¤

Chris Becker is a writer and editor with more than a decade of experience covering music, art, literature, entrepreneurship, and economics. As a composer, Becker has created music for dance, experimental video, and mixed-media installations.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

The Yardbirds, 1966. Jeff Beck, Jim McCarty, Chris Dreja, Jimmy Page and Keith Relf (from left).

The Yardbirds, 1966. Jeff Beck, Jim McCarty, Chris Dreja, Jimmy Page and Keith Relf (from left). "I've always liked to play melodically," Beck says. "Otherwise, there's nothing there, just an ugly sound."

"I've always liked to play melodically," Beck says. "Otherwise, there's nothing there, just an ugly sound."

Beastie Boys' Mike D discusses 'The Echo Chamber,' a new freeform radio show he will host on Apple Music's Beats 1 network.

Beastie Boys' Mike D discusses 'The Echo Chamber,' a new freeform radio show he will host on Apple Music's Beats 1 network.