| Author | Message |

1890 - 1900 The story of the sound recording industry is mostly a story of musical entertainment on phonograph discs for the whole period from the invention of the phonograph in 1877 to about the 1950s, when new technologies emerged. The major players in the industry were Victor, Columbia and HMV (which originally stood for His Master's Voice) until the end of World War II, and are still important today. These three companies all got their start in the 1890s, when the phonograph was still young. Thomas Edison's 1877 invention of the phonograph was followed by many imitators, most notably the "graphophone," which became the basis of the Columbia company. Both inventions used a cylinder record which captured sound in a groove. Just as the graphophone of 1887 borrowed many ideas from Edison, so too did Edison's "improved phonograph" of 1888 borrow back from the graphophone. Soon both machines were for sale or lease to the public. The primary market was intended to be businessman, lawyers, court reporters, and others who currently used stenography to capture important thoughts or compose letters. Although the sound recorder as a business machine has its own history, it is the entertainment uses of sound recording that made the biggest impact. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Emile Berliner ~ Auld Lang Syne {1890} You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Charles P. Lowe ~ Pretty Little Dark Blue Eyes {1897}

Charles P. Lowe was a popular vaudeville and concert performer, appearing occasionally as a soloist with Sousa’s band. He is the first xylophonist to record for Edison’s National Phonograph Company beginning in 1896. By 1901, he had recorded 21 titles – mainly of polkas, gallops, waltzes, and popular songs – on the standard two-minute wax cylinders. Although Lowe was the only xylophonist recording for Edison until 1902, he also recorded for many of the other cylinder companies, including the United States Phonograph Company, the New Jersey Phonograph Company, the Bettini Phonograph Laboratory, and the Reed and Dawson Company. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

This Edison phonograph cylinder recording from 1890 was made by Julius Block, a Russian Businessman of German descent (The Old Man with the Umbrella in this video) who became fascinated with the phonograph (and even convinced Tchaikovsky to sign an endorsement). .

The Dawn Of Recording (3 CD set released in 2008) track listing. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Feels strange to hear someone's voice in 1890. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

it does, it's amost a bit scary | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I love old music recordings, theres evidence of a recording from 1860 on the youtube somewhere by a french guy who used gum on a cylinder and Thomas Edison reading Mary had a little lamb in 1877. [Edited 8/14/13 4:09am] Got some kind of love for you, and I don't even know your name | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

George W. Johnson ~ The Laughing Song {1894}

George W. Johnson (1846-1914) may not be a household name, but he has a singular place in music history — he is, according to most accounts, the very first African-American recording artist. . The phonograph, or "talking machine," had been invented by Thomas Edison only few years before Johnson tracked (in 1890) a rendition of The Whistling Coon, a racist minstrel song. That recording helped give birth to what we now know as the record industry. . At the time, there was no electronic amplification of a singer's voice — artists all but shouted into a cone-shaped device, and the sound waves moved a needle etching a rotating drum of hard wax. Records had only one side. . He was born into slavery and his birthplace is unknown, but Johnson moved to New York in the 1870s and became a street performer. His songs The Whistling Coon and The Laughing Song, both essentially minstrel pieces, were the most popular American songs the 1890s record industry. Technology didn't allow for duplicating Edison cylinders at that point, so Johnson, with a pianist backing him, sang each of his songs thousands and thousands of times, at about .20 cents each. An estimated 25,000 copies were in print by 1894 alone.  This untitled photograph is believed to be a picture of Johnson recording a song. . Known discography 1891 - The Whistling Coon 1894 - The Laughing Song 1896 - Listen To The Mocking Bird 1898 - The Laughing Coon 1899 - The Whistling Girl 1901 - The Laughing Song 1903 - Carving the Duck 1906 - The Merry Mail Man (with Len Spencer)

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Very interesting and informative thread. Certainly not something you see or hear ever day. Thanks for posting!

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You're welcome. I can't imagine singing a song over 25,000 times. I guess each person who bought records in those days had unique recordings that no one else had. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I think I've read that sometimes they might have 2 or 3 machines (whatever you could get close enough to the performers) going at once--but, yeah, that's nuts. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I read a book about the early business, and it said a lot of times the recordings didn't come out well for different reasons. Like if a singer sang too low, had a cold, a musician played a wrong note, or the grooves wouldn't cut right into the shellac or whatever material was used for the records. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

I learned about everything on this thread but I don't think I ever listened to these schitts.

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

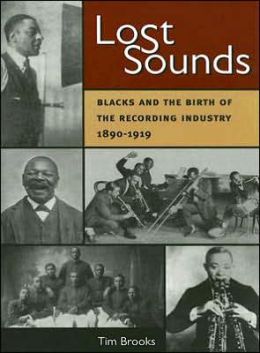

(2005) The first in-depth history of the involvement of African Americans in the earliest years of recording, this book examines the first three decades of sound recording in the United States, charting the surprising role black artists played in the period leading up to the Jazz Age. Applying more than thirty years of scholarship, Tim Brooks identifies key black artists who recorded commercially in a wide range of genres and provides revealing biographies of some forty of these audio pioneers. Brooks assesses the careers and recordings of George W. Johnson, Bert Williams, George Walker, Noble Sissle, Eubie Blake, the Fisk Jubilee Singers, W. C. Handy, James Reese Europe, Wilbur Sweatman, Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, Booker T. Washington, and boxing champion Jack Johnson, as well as a host of lesser-known voices. . Many of these pioneers faced a difficult struggle to be heard in an era of rampant discrimination and "the color line," and their stories illuminate the forces -- both black and white -- that gradually allowed African Americans greater entree into the mainstream American entertainment industry. The role played by the new mass medium of sound recording in enabling change is also explored. Because they were viewed as "novelty" or "folk" artists, nearly all of these African Americans were allowed to record in their own distinctive styles, and in practically every genre: popular music, ragtime, jazz, cabaret, classical, spoken word, poetry, and more. The sounds they preserved reflect the evolving black culture of that tumultuous and creative period. The book also discusses how many of these historic recordings are withheld from students and scholars today because of stringent U.S. copyright laws. Lost Sounds includes Brooks's selected discography of CD reissues, and an appendix by Dick Spottswood describing early recordings by black artists in the Caribbean and South America. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

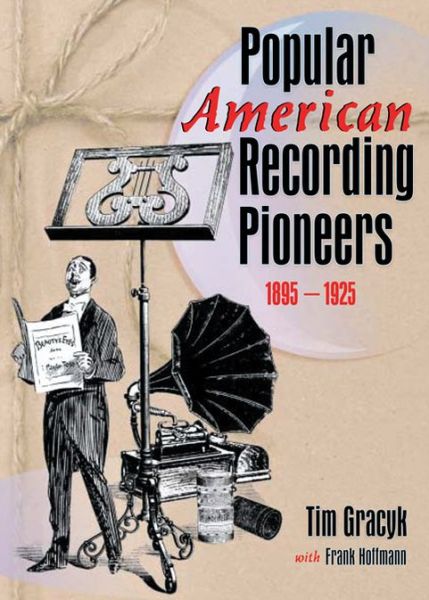

(2001) This book covers artists who, from the 1890s to the mid-1920s, made records of music that was "popular" in nature, as opposed to records of operatic arias, symphonic works, or concert pieces. Today we call this period the industry's acoustic era. A pre-electric method for recording was used, with musicians performing into a horn, not a microphone. . The year 1895 in this book's title is a bit arbitrary but around this time the commercial recording industry began to look like a real industry. It actually began around 1889 but suffered years of financial uncertainty, with even the North American Phonograph Company thrown into bankruptcy after the Panic of 1893. Companies suffered setbacks in subsequent years, but after 1895 there was no question that a recording industry would exist. . The year 1925, which marks the beginning of the electric recording era, is a convenient cut-off point. The earlier process required musicians to perform into a large horn or what some would later recall as being a funnel or tube. It was essentially an inverted megaphone. Studios were equipped with horns of all sizes, shapes and lengths--some round, some square, some flared at the mouth. Horns were carefully selected to suit the orchestras or voices that would be recorded during a session. Sound was carried via the horn into a recording machine, which was usually in an adjacent room. The energy of sound waves activated a diaphragm attached to a stylus which transferred vibration patterns to the surface of a blank recording disc or cylinder. Today this is called an acoustic recording process. Not all records issued after 1925 were made with a microphone. Columbia for four years continued to use non-electric recording equipment for its budget-priced labels, including Harmony, Velvet Tone, and Diva. . Some of the 100 artists with separate entries in the book include the American Quartet, Billy Murray (new information!), Ada Jones, Steve Porter, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Paul Whiteman, George J. Gaskin, Carl Fenton, Sam Ash, Frank C. Stanley, Aileen Stanley, Henry Burr, the Peerless Quartet, Arthur Collins, Byron G. Harlan, Sam Lanin, Bert Williams, Frisco Jazz Band, Olive Kline, J. W. Myers, Ben Selvin, the Green Brothers, Marion Harris, Haydn Quartet, Arthur Fields, Conway's Band, countertenor Richard Jose, Irving Kaufman, Will F. Denny...many, many more! You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Vess L. Ossman ~ Whistling Rufus {1899}

Vess L. Ossman, “The King of the Banjo”, was born Sylvester Louis Ossman on August 21, 1868. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

(2003) Have records, compact discs, and other sound reproduction equipment merely provided American listeners with pleasant diversions, or have more important historical and cultural influences flowed through them? Do recording machines simply capture what's already out there, or is the music somehow transformed in the process of documentation and dissemination? How would our lives be different without these machines? Such questions arise when we stop taking for granted both the phenomenon of recorded music and the phonograph itself.

In Recorded Music in American Life, historian and musician William Howland Kenney examines the interplay between recorded music and the key social, political, and economic forces in America during the phonograph's rise and fall as the dominant medium of popular recorded sound. He addresses such vital issues as the place of multiculturalism in the phonograph's history, the roles of women as record-player listeners and performers, the belated commercial legitimacy of rhythm-and-blues recordings, the "hit record" phenomenon in the wake of the Great Depression, the origins of the rock-and-roll revolution, and the shifting place of popular recorded music in America's personal and cultural memories. Kenney convincingly argues that the phonograph and the recording industry served neither to impose a preference for high culture nor a degraded popular taste, but rather expressed a diverse set of sensibilities whereby people from every social strata found a new kind of pleasure. Students and scholars of American music, culture, commerce, and history -- as well as fans and collectors interested in this phase of our nation's rich artistic past -- will find a great deal of thorough research and fresh scholarship to enjoy in these pages. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Footage of a clog dancing contest in the 1890's, no sound You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Dancing girls & swans, 1896 [Edited 9/9/13 20:45pm] You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 by Lynn Abbott & Doug Seroff . (2003) American popular music style was sparking. These were some of the worst years in American race relations, yet they witnessed the emergence of ragtime and the birth of an African American popular entertainment industry. Out of Sight is the first book dedicated to this signal period of black musical development. . It is a landmark study, based on thousands of music-related references mined by the authors from a variety of contemporaneous sources, especially African American community newspapers. The citations are organized and explained in a way that clears a path through the dense landscape of this neglected period in black music history. Accompanying the text are 150 halftones, also excavated from period sources, offering a broad pictorial canvas of African American music during the years before ragtime's commercial ascendancy. . Out of Sight examines musical personalities, issues, and events in context. It confronts the inescapable marketplace concessions musicians made to the period's prevailing racist sentiment. With detail never available in a book before, it describes the worldwide travels of jubilee singing companies, the plight of the great black prima donnas, and the evolutions of "authentic" African American minstrels. With its access to newspapers and photos, Out of Sight puts a face on musical activity in the insular black communities of the day. . Drawing on hard-to-access archival sources and song collections, the book is of crucial importance for understanding the roots of jazz, blues, and gospel. It is essential for comprehending the evolution and dissemination of African American popular music from 1900 to the present. Out of Sight paints a rich picture of musical variety, personalities, issues, and changes during the period that shaped American popular music and culture for the next hundred years. . . Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, "Coon Songs," and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz by Lynn Abbott & Doug Seroff . (2007) The commercial explosion of ragtime in the early twentieth century created previously unimagined opportunities for black performers. However, every prospect was mitigated by systemic racism. The biggest hits of the ragtime era weren't Scott Joplin's stately piano rags. "Coon songs," with their ugly name, defined ragtime for the masses, and played a transitional role in the commercial ascendancy of blues and jazz. . In Ragged but Right, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff investigate black musical comedy productions, sideshow bands, and itinerant tented minstrel shows. Ragtime history is crowned by the "big shows," the stunning musical comedy successes of Williams and Walker, Bob Cole, and Ernest Hogan. Under the big tent of Tolliver's Smart Set, Ma Rainey, Clara Smith, and others were converted from "coon shouters" to "blues singers."

. Throughout the ragtime era and into the era of blues and jazz, circuses and Wild West shows exploited the popular demand for black music and culture, yet segregated and subordinated black performers to the sideshow tent. Not to be confused with their nineteenth-century white predecessors, black, tented minstrel shows such as the Rabbit's Foot and Silas Green from New Orleans provided blues and jazz-heavy vernacular entertainment that black southern audiences identified with and took pride in. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable