I have missed a lot of these threads so I'm sorry if these have already been posted.

Gene Kelly's widow revealed last year that Gene wanted to do a musical with Michael.

“He always got the new records,” his widow says. “He stayed current. He appreciated break dancing. He really liked ‘Purple Rain’… He tried very hard to get Michael Jackson to do a musical, but I guess there was this thinking that, oh, Gene’s too old to get it.

“Well, when Michael Jackson died, and all the obits talked about Michael dancing in penny loafers — where do they think that came from?”

At 7:30 you can hear her discussing it.

http://www.voicebase.com/...jackson%22

She thinks that it would have been amazing.

Gene was very interested in all types of music and actively kept abreast of what was new and “hot.” Whenever the LA Times critic Robert Heilburn published his list of the most popular recordings, Gene cut it from the paper and sent me to Tower Records to buy copies of each album (actually cassette tapes back then!). I remember in particular picking up copies of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, Prince’s Purple Rain, Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, Janet Jackson’s Control, Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run and Born in the U.S.A. He would listen to them all. Gene always said that dance followed music, so he wanted to know what would be influencing the new styles of dance. He said, “Styles change, things change. When Elvis and the Beatles came in, Astaire and I went out. They had a whole new kind of music and a whole new kind of youth following. Television was in and the first mass media was not the motion pictures. It changed to television.”

http://patriciawardkelly.wordpress.com/

On to Astaire:

In the early 80s I was working on an autobiographical project with Hermes Pan who was Fred Astaire’s dance collaborator and longtime friend. About that time Michael Jackson got himself introduced to these two men who, although no longer working, had produced possibly the greatest oeuvre of dance performances in the history of film.

Their meeting might have come through Hermes, who was a very sunny man with an elfin-like appreciation of people and dancers especially, and far more congenial and socially accessible than Astaire.

“Dancers,” Hermes once said, “are like children; they have to be in order to get up there and do that.” And then he chuckled at the reality.

I don’t know which of the two men – Hermes and Fred – saw Michael Jackson’s work first but whoever it was, he immediately told the other. Fred Astaire thought Michael Jackson was the greatest dancer of his age. He regarded Michael as his peer. Hermes agreed. He thought Michael was Fred’s natural successor.

After Michael and the two men became friends, Michael one day sent Fred Astaire all of his gold records. Or was it platinum. There were a lot of them and in their frames. Astaire was non-plussed. There was nothing ethereal about the man off-screen, and this sort of thing struck him as bizarre. He sent them back. It did not affect his relationship with Michael, however, because Michael was his peer. Furthermore Fred Astaire was flattered to see that the pop mega-star who he considered the greatest dancer was inspired by certain Astaire dance moves.

I never quite understood that last bit about the dance moves when Hermes mentioned them. Michael Jackson seemed like such a different breed of cat, style-wise, than Fred Astaire to this non-dancer Nevertheless, I knew they knew what they are talking about.

Thinking about that last night, we found couple of clips of the two boys doing their thing, thrilling us masses of millions in their thrall. Coincidentally they bear out what Hermes Pan told me about Michael and Fred and their dancing: they were the resident genius of their time.

Whatever it was for him, it was a tortuous, troubled, and possibly even tragic life for the boy/man, this Nijinsky child who wanted his peers to have his prizes, to gain some camaraderie, to share some space in that strangely lonely place called fame. In summation he was the dancer. The rest of us got the best of him and that will be his legacy.

http://www.newyorksociald...ode/512718

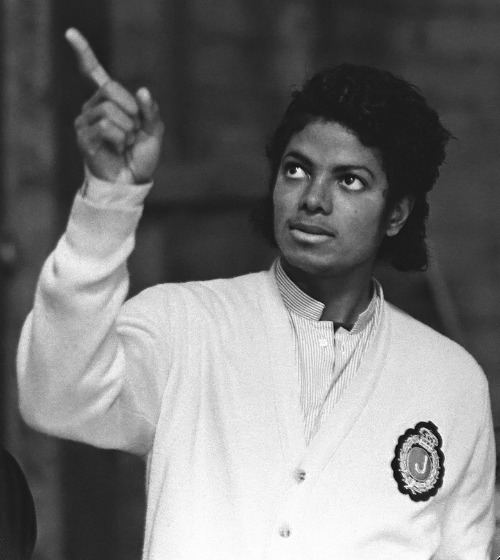

Then come the landmark videos of the early nineteen-eighties: “Billie Jean,” “Beat It,” and “Thriller,” all of them for songs that appeared on the collection “Thriller” (1982), which is the best-selling album of all time. At this point, Jackson has just about everything you would want in a dancer. He is very fast, and, now that the adult musculature has come in, his whole body is “worked.” (This means that every muscle is stretched, and operating in the service of the dance. Nothing is blurred.) As a result, he has a sharp attack, and wonderful clarity. Watch him—as you can, for example, in “The Way You Make Me Feel” (1987)—dancing, silhouetted, alongside other men doing the same steps. You can’t see the faces, but you know which one he is. He dives into a step more intently, and shows it to us more precisely, than anyone else.

The “Thriller”-period videos were instrumental in converting MTV from a backwater to a sensation. Jackson consciously aimed at doing that. “I wanted to be a pioneer in this relatively new medium,” he said in his 1988 memoir, “Moon Walk” (a book, incidentally, edited by Jacqueline Onassis). He spent a fortune on these projects. The 1995 “Scream” video cost seven million dollars—a record at that time. He didn’t like to call these works videos. They were “short films,” he claimed—and rightly, for he had them shot not on videotape but on 35-mm. film. “We were serious,” he said.

Jackson took his choreography from a number of sources: hip-hop, sock hop, “Soul Train,” disco, and jazz dance, plus a little tap and Charleston. By his account, he constructed some of the movement himself.

But on most of his dances he did not work alone. Michael Peters, Vincent Paterson, and Jeffrey Daniel, all of them experienced stage and TV choreographers, collaborated with Jackson. On the PBS special “Everybody Dance Now” (1991), in answer to a question from the dance historian Sally Sommer, Peters said that Jackson’s method was to put together some steps and ideas and bring them to a choreographer, who would then organize them into a coherent dance.

But, whether he went it alone or got help, the result was much the same. He didn’t have a lot of moves. You can almost count them on your fingers: the gyrating hips, the bending knees (reversing from inward to outward), the pivoting feet (ditto), the one raised knee, the spins, and, above all, the rotated or raised heel, which is what he gets around on. These steps are generally done staccato. He finishes the phrase and freezes, then finishes the next phrase and freezes. He also has some moves so natural that one hesitates to call them steps: lovely, light-footed walks, struts, jumps, and runs. He made at least one important innovation in music-video choreography—the use of large ensembles dancing behind the soloist—but beyond that he created very little dancing that was different from his own prior numbers, or anyone else’s. Yet many people were happy to see him, again and again, do the thing he did. Long after the critics soured on his music and his videos, they still liked his dancing.

Jackson, who had a thorough knowledge of the movie musical, revered Fred Astaire. He records in his memoir how thrilled he was when Astaire praised him. The old master even invited him over to his house, where Jackson taught the moonwalk to him and his choreographer Hermes Pan. (Astaire told Jackson that both of them, he and Jackson, danced out of anger—an interesting remark, at least about Astaire.) But despite Jackson’s awe of his predecessor, he never learned the two rules that Astaire, as soon as he gained power over the filming, insisted on: (1) don’t interrupt the dance with reaction shots or any other extraneous shots, and (2) favor a full-body shot over a closeup.

To Astaire, the dance was primary—his main story—and he had it filmed accordingly. In Jackson’s videos, the dance is tertiary, even quaternary (after the song and the story and the filming). The camera repeatedly cuts away, and, when it comes back, it often limits itself to the upper body. Jackson didn’t value his dancing enough.

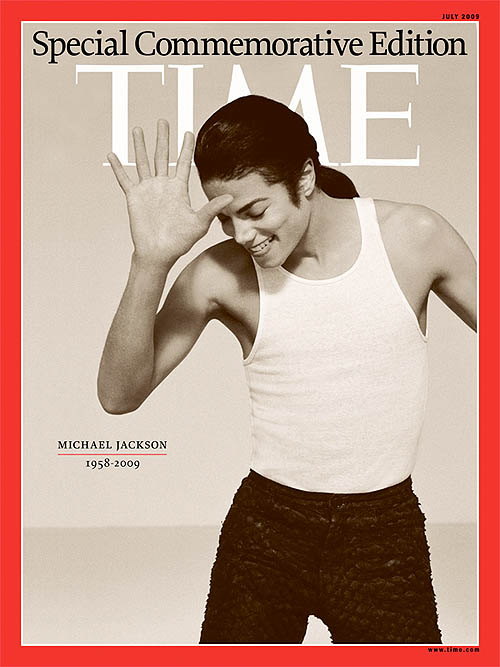

The last known video shows him at a rehearsal for the London season he was about to embark on. He struts, he boogies; he snaps and pops. As CNN’s chief medical correspondent, Sanjay Gupta, said, “This doesn’t look like someone who’s very sick to me.” That’s not to mention that Jackson was fifty years old and, because he was in rehearsal, was probably not performing “full out.” He was still a great dancer. Two days later, he was dead.

http://www.newyorker.com/...rentPage=1

I don't remember the source for this but:

I think it's worth noting the style in which Jackson's clips were filmed: long takes, fluid camerawork with minimal editing, often framed full-on, like Fred Astaire's numbers. So you can see and appreciate everything he's doing.

His film performances eventually grew compromised by a reliance on special effects and directors with no talent for shooting dance -- among them Francis Ford Coppola, who managed to undermine Jackson, Gregory Hines and Fred Astaire in various projects, making him Hollywood's champion dance-killer.

Can anyone, then, dance like Michael Jackson? Only if you can rise up on your toes without toe shoes, stay there, and keep up what is basically a nonstop two-hour solo.

Marcel Marceau, the great mime, would do the backwards walk. It was never called Moonwalk and I doubt Marcel invented it either. But I am pretty sure it originated with mimes. And Marcel was a lot older than Cab Calloway and all those jazz fellows of the 30's. And you'll notice in MJ's videos that his movements, were always very mime-like. And his dance moves were clearly Astaire and Kelley. When he'd combine those with the mime and a faster beat, you got Michael Jackson. So MJ did not invent dance or mime, but he did invent the combining of all of them.

The movements are best described as pulses that travel through the body, arriving at another area and continuing the beat. Joan Acocella, journalist and dance critic for the New Yorker, cites Jackson’s sources of movement as break dancing, “hip-hop, sock hop, ‘Soul Train,’ disco, and jazz dance, plus a little tap and Charleston,”

She suggests that Jackson’s virtuosity lies in the precision of his movements, coupled with their speed and pacing.49

In fact, the two qualities that writers refer to consistently as Jackson’s most stunning qualities are his quickness and control; he adds in steps between the musical beats so swiftly they can scarcely be seen and yet maintains full control over his body—all while maintaining a consistent flow. Hamera calls the dance “liquid and percussive,” Reece Livingstone “fluid yet disjointed,” but either way, critics agree about the sharp attack of the movement that somehow manages to remain fluid.50

On the kick, the leg actually fully extends but does so quickly enough that one registers only the bent knee, raised and held at ninety degrees, demonstrating Jackson’s ability to fully complete each movement no matter the speed of the movement itself.51

One might suspect the embellishments and tapping to be improvised or added to regain balance, only Jackson repeats exactly the same sequence in the other direction. Every move is perfectly controlled, executed at blinding speed and with perfect musicality, characteristics that defined all his movements and played such a role in his signature.

Despite the rigid control, Jackson attacks each movement with intensity and commitment, which comes across as unmatched clarity and efficiency.52 The easiest way to see this is by comparing his dancing with that of his backup dancers, such as during the silhouette sequence of The Way You Make Me Feel.

The differences between Jackson and the dancers are subtle, but telling. For example, during the split-second pause before the right knee drops, the dancer next to Jackson never comes to a complete stop. His right leg displays a very slight movement in preparation to go to the ground, a compensation to remain balanced. This preparatory movement is absent from Jackson, who arrives at the pose and comes to a complete stop before moving on. As the knees open and close under the body, the dancer pulses his shoulders, using them to gather his knees underneath him or embellish the movement. Jackson’s shoulders move very minimally, so the movement of the knees is unmarred by any other movement in the body. The cleaner movement creates a more startling visual effect. In analyzing other similar sequences of Jackson and his backup dancers, the others consistently display these subtle preparatory movements or add slight embellishments.

These are not obvious, but the lack of them in Jackson’s body creates the impression that movement simply explodes from it without being forced. It is a characteristic that defines all Jackson’s movements.

The same effortless quality is, along with the unparalleled sharpness of quick movements, one of the most significant aspects of Jackson’s movement signature. In the forward to Moonwalk, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis wrote that Jackson was a dancer who “seems to defy gravity,” something that can especially be seen in his moonwalk, struts, and glides.53

The effect of floating can be seen in all of the dancer’s upper bodies, but the telling differences are found in the feet. In very general terms, the move is accomplished by turning in the right foot and taking the weight on the ball of the foot, while the left slides backwards to join it. For the other dancers, the left food slide is heavier and the circle traced by the feet is much smaller than Jackson’s. With the other dancers, there is always the slight betrayal of shifting weight, in a bending knee or a more sudden step. Jackson, on the other hand, gives no hint whatsoever of which foot is carrying the weight. As a result, neither appears to have it, and he simply floats around the circle. All his struts, spins, and of course, moonwalks, reveal this effortless, weightless quality.

The idea that Jackson’s dancing seemed to transcend the laws of physics is perhaps the best way to sum up what made it so particular to him. His dancers are remarkable in their own right, but never quite as clear, as quick, as sharp, or as effortless as Jackson. He arrives fully at each new pose before moving on, taking each movement to its full potential, so that movements that are not technically difficult appear technical but are executed without any apparent effort. He is perfectly controlled, yet his dancing is visceral, wild, and explosive.

What is so remarkable is that Jackson himself is the only one who can perform these moves in this way. Although the moves are not “his,” his ability to perform them in a unique way allows the spectator to view them as though they were Jackson’s own composition.

One way to see this is by studying Michael Jackson impersonators, people who have dedicated much of their lives to replicating the quality of Jackson’s movement signature. The best come close, but they are always betrayed by 19

the smallest visible changes in weight, taking the movement past the line (instead of exactly to it as Jackson does), not coming to a full stop of motion, or simply losing, for a second, the attack of the movement omnipresent with Jackson.

From MJ's autobiography and a Hermes Pan book.

It was the greatest compliment I had ever received in my life, and the only one I had ever wanted to believe. For Fred Astaire to tell me that meant more to me than anything. Later my performance was nominated for an Emmy Award in a musical category, but I lost to Leontyne Price. It didn't matter. Fred Astaire had told me things I would never forget - that was my reward. Later he invited me to his house, and there were more compliments from him until I really blushed. He went over my "Billie Jean" performance, step by step. The great choreographer Hermes Pan, who had choreographed Fred's dances in the movies, came over, and I showed them how to Moonwalk and demonstrated some other steps that really interested them."

He received a call from Fred Astaire asking him to come home immediately. Thinking it was some kind of emergency, Hermes rushed over only to find Astaire excitedly watching a videotape. “Just wait till you see this,” he said by way of greeting. Pan sat beside him and the two watched Michael Jackson perform “Billie Jean” on Motown 25:Yesterday, Today, Forever, which had aired the night before. Impressed by the performance, Pan persuaded Astaire to call Michael Jackson to congratulate him.

Somehow Fred tracked (Michael) down. He told him that he was one hell of a dancer… “You really put them on their asses that night. You’re angry dancer. I’m the same way.” …I was surprised that a person that dances with such anger would have such a soft voice. I told him how much I enjoyed his work, and he was very gracious, very excited to hear from us. For a moment, I thought he believed it was a practical joke. I liked him right away because he seemed unaffected by show business and seemed star struck. He really could not believe that Fred Astaire had called him. –Hermes Pan: The Man who danced with Fred Astaire

Mozart:

1.) Mozart showed prodigious abilities in music at a very early age. The same can be said with Michael Jackson's vocal and musical abilities.

2.) At the age of five Mozart began performing before European royalty and all over Europe. Michael Jackson made his debut at a talent show in Gary, Indiana and later performed throughout the Midwest and in nearby Chicago night clubs.

3.) Leopold Mozart, his father, became his teacher, mentor, and manager. Joe Jackson became his son's manager, coach, and advisor.

4.) Mozart and his sister, Maria Anna or Nannerl, performed together as child prodigies. MJ and Janet performed together as children on television variety shows with the Jackson 5.

5.) At seventeen Mozart was hired as a court musician to the Prince Archbishop Colloredo in Salzburg, Austria. He composed and performed many of his symphonies, sonatas, serenades, and other musical pieces to a huge following in Salzburg. Michael Jackson debuted as an entertainer at age 10 with the Jackson 5, later to a recording contract with Motown Records in Detroit, and by having a huge legion of fans, selling out concerts, and having hit songs on the pop charts.

) Mozart broke free of his restricting ties in Salzburg to the Prince Archbishop and to his father. He then embarked on being a freelance performer and composer in Vienna, Austria. In 1971 Michael Jackson embarked on a solo career while still a member of the Jackson 5. In 1979 he joined forces with record producer, Quincy Jones, for his first album "Off the Wall".

7.) During Mozart's Vienna years he composed his world famous opera in 1786, "The Marriage of Figaro", which is still performed in opera houses throughout the world. Michael Jackson in 1982 gave the world "Thriller", the best-selling album of all time.

8.) Mozart was a small man, very thin, and pale. MJ was described by many journalists, after his death, who had seen him during the trials and his last rehearsal as a small man, very thin, and pale due to his skin condition, which grew worse in later years.

.) His wife Constanze described Mozart's voice in a letter as rather soft in speaking and delicate in singing. However, when it was necessary to exert his singing voice it was powerful and energetic. Michael Jackson was well-known for his very soft-spoken speaking voice, yet his singing voice was powerful and energetic.

11.) Mozart and Michael Jackson had extremely conflicting feelings about their fathers due to the controlling and manipulative ways early in their careers as well as in childhood.

12.) In the film "Amadeus" Mozart came across as childish, immature, and crude. MJ was a child-like man in later years, highly eccentric, and displayed illicit behavior with his infamous crotch-grabbing moves after the release of his "Bad" album.

13.) In the latter part of their lives each were in deep financial debt.

14.) Mozart was in the midst of composing his famous work, the "Requiem". Michael Jackson was in the process of preparing for his "This is It" 50-city tour before their deaths.

http://voices.yahoo.com/michael-jackson-mozart-3738106.html?cat=33

Mozart also had an older mentor in Joseph Hadyn. Musically they aren't on the same level obviously.

*Michael Jackson has been dead for more than three years now, and new books attempting to “analyze” and “explain” who he was are still emerging.

*Michael Jackson has been dead for more than three years now, and new books attempting to “analyze” and “explain” who he was are still emerging. New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

moderator

moderator

will ALWAYS think of

will ALWAYS think of  like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.

like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.