The voice behind the Archies talks about a long career singing and producing great pop music.

by Jay S. Jacobs

Copyright ©2000 PopEntertainment.com. All rights reserved.

Let me know a bit about how you got started in music.

I grew up in a singing type of family. My dad sang all over the place. His brother sang, you know, just for their own enjoyment… at weddings and things. But there was a lot of singing going on in our home. My dad was a big pop music fan. He had all the latest 78s of the hit records of the fifties. So I would listen to all of his records and see him enjoying it and I think I just naturally gravitated to singing. When I was about eleven, I broke my arm, and I needed an exercise for my wrist. The doctor recommended a guitar, because I was a big Elvis fan. I started to play, and before you knew it I was singing with my guitar and writing songs.

Your first hit was "Leader of the Laundromat," a parody of the girl-group classic "Leader of the Pack," which you did with a band you called the Detergents. How did that come about?

Two of my friends, Danny Jordan and Tommy Wynn, we were all staff writers at Don Kirshner’s publishing company. Danny’s uncle was a guy named Paul Vance, who was a very successful songwriter in the fifties and sixties. He wrote "Catch a Falling Star" for Perry Como. He wrote "Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini" for Brian Hyland. He was very talented. He came up with this idea to do a parody of "Leader of the Pack." He asked Danny to bring in a couple of friends. Danny and I blew on over and we ended up singing on this parody. It became a career for a couple of years. We went out and toured on the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars singing "Leader of the Laundromat."

Do you remember the first time that you heard your music, on the radio or in a club or something like that? What happened, and what was it like?

Actually, I recorded for Paul Vance as a solo artist in 1964-1965. (I did) a song called "Don’t Stand Up In A Canoe" which was kind of an "Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini" type of record. I remember hearing it on the big New York station one day. For a week they played it or two weeks. It was the culmination of my whole career, to hear myself on the radio. That’s what I wanted all my life.

You did a lot of songwriting for Don Kirshner. What were some of the hits that you wrote for other musicians?

To tell you the truth, I was never a hit songwriter. I became a hit singer, and hit producer, but my songwriting… it’s very tough to become a hit songwriter. It takes a lot of luck and pizzazz and a lot of connections, and at that point in my career I was more of a singer and performer than I was a writer. But I did sign to his company and I wrote songs for Jay and the Americans, Johnny Mathis, the McCoys, James Darren, Gary Lewis and the Playboys. Gene Pitney recorded my songs. Bobby Vee. All these great sixties artists. I got a lot of my songs recorded. It was a very wonderful time because I got to meet all the artists that I was such a big fan of. But really, the songwriting was a means to an end for me, to get my voice on record and to become a hit singer. That’s really what I was after.

Then came the Archies. How did you get involved doing music for the show, and how did it feel to be known as the voice for a cartoon?

It was a great gift at the time. I was a studio singer. I had developed into a singer of commercials. So I did tons of jingles. Every week I would do ten or fifteen commercials. I did backgrounds for all the record companies that were doing their records in New York City at the time. When I heard about the Archies sessions, a friend of mine was playing on it. He said they don’t have the voice of Archie yet. They don’t have the lead voice for all this music they’re doing for this new TV series based on the cartoon. I went up and auditioned for my old friend Don Kirshner, who was the music supervisor. My other buddy, Jeff Barry, was the line producer. I kind of gave them a few different sounds, and they locked into one specific sound that I made and said you’ll be the voice of Archie. I knew it would get a big push, because Don Kirshner was like PT Barnum. He could promote anything. It became the number one show in its timeslot. We did two songs a show, plus the theme. So I got to hear my voice every Saturday morning. The records got really big promotion from Kirshner and… at the time… RCA Records.

VH-1 Classic has been showing a video of you performing "Sugar Sugar" in the 70s. Do you know where that came from?

I think that came from a Cleveland show Upbeat. I think I did that for them. Or, I did the Larry Kane show in Houston, Texas. One of those two shows. They were teen shows that played music, and I remember going to the show and singing "Sugar Sugar" four or five times, playing different instruments. I never saw the composite they put together, but obviously they put one together of me and it looks like there are like four or five of me in the band. I did it in about 1970, and it was a real kick to do that and I love that video. I think it looks amazing.

Pop singer Ken Sharp just recorded "Melody Hill" with Carnie Wilson on backing vocals, and Jellyfish used to play "Sugar & Spice" live. How does it feel to hear other people redoing your songs?

It’s fine. It’s a kind of bittersweet thing to hear your songs, the things you made famous, recorded by other people. It’s interesting to see their take on the vocals. I’ve heard four or five versions of "Sugar Sugar" over the years, and it’s always interesting to me. I thought that there was obviously only one way to sing it. Yet, when I heard Wilson Pickett’s version, or Andy Kim had a version, Tommy Roe had a version, and they were all very different. Everybody has a different vocal take on it. Honestly, I think I caught the best version of it. (Laughs) I just got the generic feel for it. I was the first one to record the song and I think I was the right voice at the right time for that song.

The Archies music has never really come out on CD in any decent compilations, I have an old CD called 20 Greatest Hits that only has ten songs on it and has a really bad, obviously fake drawing of the Archies on it. Everything else in the world seems to come out on CD, why has it been so hard to get good Archies disks, and is that going to change?

Yes, there are many plans. There has been a rights battle over the years between Archie comic book people and Don Kirshner and the Filmation people, who had the original cartoon. Nobody was really sure who had the right. Lately, I think they’ve come around. Fuel 2000 is a record label and they put out Absolutely the Best of the Archies. I hear that’s a pretty good compilation. A company called RKO Unique has put out two versions of Archies albums with my picture on the cover. If you’re ever on the Internet you can check them out. They’re in the stores too. They’re pretty good, they’re the original Jingle Jangle album and the original Everything’s Archie album. There are plans to put out the final three or four albums that I did through RKO Unique/Boardwalk. They just bought the Boardwalk label. Look for that.

Your next band was the Cuff Links, and despite the fact that you were a one-man band, the record label made up extensive fake bios for a whole group. Whose idea was that and how did you feel about it that they were trying to make them out to be someone other than you?

I didn’t mind it at all. I did the deal… it was with Paul Vance again. The "Laundromat" guy. He came up with this song "Tracy." He called me when the Archies were really taking off. He said would you do me a favor? Come in and sing this song. He said it had to be a song I liked. I listened to "Tracy" and I just loved the song. So I said, if it does become I hit, I’ll do an entire album, because I’d love to sing an entire album of your songs. Paul Vance and Lee Pockriss songs. There were two songwriters and producers on it. Sure enough, "Tracy" took off and sold like 900,000 copies at the time. So I did do the album. I didn’t pay too much attention, I didn’t know they put together a group and sent it on the road. By the time I found out, it was already old news. I was very happy to have "Tracy" out at the time, because "Sugar Sugar" and "Tracy" were both in the top 10 at the same time. That was a great feeling to know that I'd spent my early years trying to get hit records and now I had two. Unfortunately, my name wasn’t on either one. So again, it was a double-edged sword. God gave me what I wanted, but not quite the way I wanted it.

I could never understand how "Early in the Morning" didn’t become a smash hit. I know Gene Pitney released it as a single, but it didn’t do too well. Was the Cuff Links version released as a single?

No, we didn’t release it. Girl names were very popular with the Cuff Links. We released "Tracy,"

That’s a great song too…

… then "Run Sally Run."

"Tracy" was used on Ally McBeal a couple of years ago. What did you think of that?

It was the coolest thing in the world. Because Ally McBeal was one of the top 10 shows in the country. Everybody watched it at some point. So to have my voice singing behind Tracey Ullman’s guest appearance was a real, real kick. I can’t tell you how many e-mails and phone calls I got over that play. It was a great thing. It really brought me up to this generation, too, with "Tracy." Now when I sing "Tracy" at these concerts and summer fairs that I’ll be doing, a lot of people watched Ally McBeal and know that song.

Again, with the exception of a few singles, the Cuff Links work is hard to find on CD. Have you ever discussed with a label like Varese Vintage the idea of releasing the two Cuff Link albums as a single CD, or maybe doing a Best of CD that collects songs from all of your bands and solo work, like the Tony Burrows CD?

Nobody’s talked to me about that lately. I know you can buy a version of it from Japan on Amazon.com. But nobody’s talked to me about putting out the Cuff Links album, which is a very good idea, actually.

Did you ever want to make any of those bands a fulltime gig, or were you enjoying the variety of playing in all different situations with different people?

They offered me the job of doing the Archies after we had it. But it was more of a cartoon children’s thing. I was hoping to become more of an Elton John type of guy. Somebody with a little more credibility than the cartoon group… the preteen and the teen market. So I didn’t jump at the opportunity. It never crossed my mind. I segued from singing commercials to doing these pop records, and then I segued into production. All through the seventies and early eighties, most of my time was spent producing other people. Also, I was living in New York City, I was married, I really wanted to have a family, so I didn’t want to go on the road much. I chose an occupation that kept me in the studios of New York, instead of on the road in the middle of the country.

Speaking of the teen marketing, a friend of mine has a very strong childhood memory of reading a little thing in Archie Comics about you that read, "Girls, he’s a real ladies man. And boys, he’s a real he-man." Did you ever think it was weird the way you were marketed?

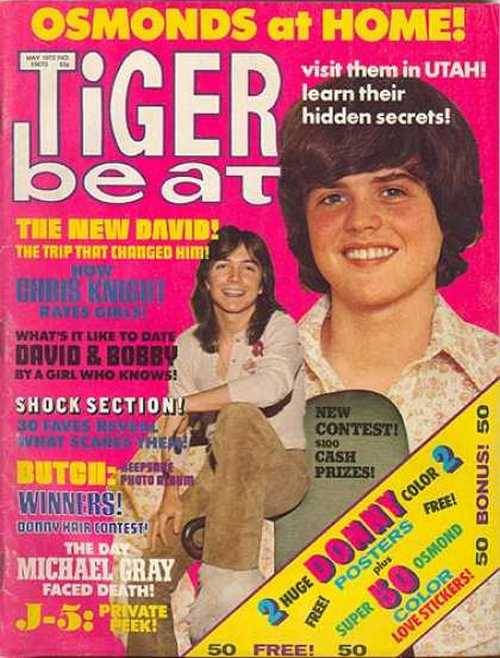

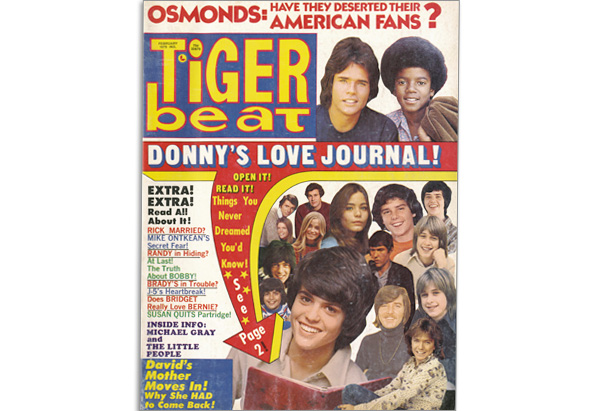

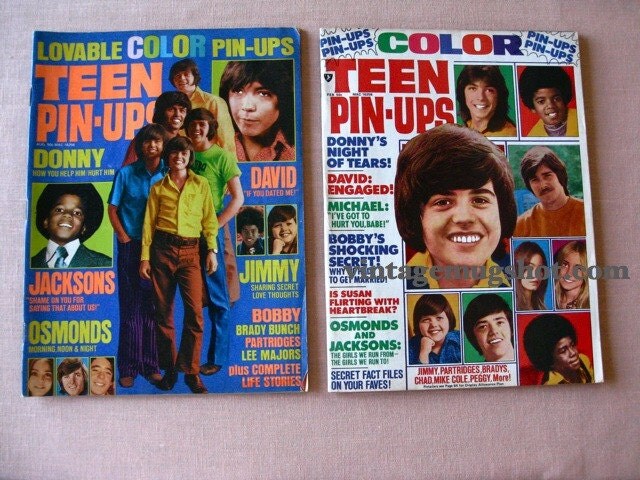

I thought that was horrible. I really didn’t think that was an appropriate approach for me. The people who were doing these things, I didn’t even know they were doing them. People were just taking my picture and putting words under them. In 16 magazine they put down stories about my likes and dislikes that had nothing to do with me. But, that’s part of the machinery. Once it gets going, it has a life of its own. You have to take the good and the bad. The good part of it is that a lot of people get to know you. The bad part is that they don’t get the real facts. You don’t get the real image of who I am and who I was. But, all in all, I’d do it again.

In the early seventies after all of those hits, you recorded a lot as a solo act, but except for a minor hit with "Let Me Bring You Up" the solo stuff didn't really take off. Why do you think that may have been?

I just think my focus was not on being an artist after the first couple of albums I did solo. I segued back into singing commercials regularly, every day, and producing other people.

What were some of the commercial jingles that you did?

I sang for McDonalds. I sang on the huge Coke commercial on the top of the mountain, "I’d Like To Teach the World To Sing." I was the voice of Campbell’s Soup, General Tires. I was the voice of Tang. I must have done over a thousand commercials in my career. Everything you can name I probably sung once. Or twice. I’ve done a dozen of those McDonalds’ commercials. Dr. Pepper, I was the voice of "I’m A Pepper, You’re a Pepper."

I saw on the internet that you also recorded the "Spiderman Theme" which I had never heard before. Was that really you?

Yes, but it really was the theme for a record called Spiderman. Which is Tales from Beyond, or something like that. It was a radio show on record with four or five songs that I was the voice of Spiderman on.

I know of about eight bands that you recorded with. Do you have any idea how many there have been totally?

You know, I’ve forgotten over the years. Because, a lot of the stuff I did, people put out on me without me even knowing. I would go into the studio, take a flat fee and let them put the records out. I know of about fifteen. I’d bet there’s about thirty groups that I was over the years. Most of them, they renamed my groups, so whatever they said they were going to call it, they didn’t call it. People put out my demos, I was a big demos singer for all the songwriters in New York City. Sometimes the demos were better than the final records that they put out. So they put out my demos and they called it a group name.

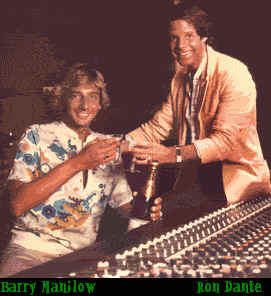

By the early seventies, you had moved from being a pure performer into production. Your best-known work was probably with a then unknown pianist named Barry Manilow. How did you hook up with him, and what were the years working with him at the height of his popularity like?

Barry and I met doing a commercial. On that session singing were myself, Barry Manilow, Melissa Manchester and Valerie Simpson from Ashford and Simpson. It was a really good group. Barry and I hit it off. He knew of my credits and he told me he was working with a new artist that was just putting out some records, Bette Midler. I’d just seen her the night before on The Tonight Show. I thought she was going to be a big star. I said, let me hear some of your songs. So in the following days, we got together and he played me some of his songs. I felt I could make him a star. I just knew it. I had the contacts, I had the talent to get his voice on tape. We went in and did the first demos he really did under his own name. I got him the record deal and about a year and a half later we had "Mandy." We worked together until about 1981. About six-seven years, we did ten albums. Those years were great years. Easy… just the happiest years recording in the studio. It’s just a pleasure to work with the guy. He’s a real professional. Easy going and a really good singer.

You have also produced people like Pat Benatar and Cher. What did you do with them, and who else have you worked with?

With Benatar, the record company brought me to her because she was singing in nightclubs in New York City and she was doing big ballads. They asked me to go down and take a look at her. I looked at her and I said I think I can turn her into a rock and roll singer. I took her into the studio and I recorded a song called "Heartbreaker" and another song called "You Better Run." I even did another song on that tape, an old Roy Orbison song called "Crying." Which consequently somebody else and had a hit with…

Right, Don McLean…

Yeah. But I had an incredible vision for her and it worked. Chrysalis put her out and she became a big star. I worked Cher on the Take Me Home album, the one where she’s wearing kind of a strange outfit on the cover. She was a delight to work with. A real professional. Showed up early and stayed late. And sang great in the studio. I really like Cher. I worked with Dionne Warwick on "I’ll Never Love This Way Again." Produced different people, like for TV specials I worked with Ray Charles and John Denver. I worked with the girl from Fame, Irene Cara. I produced an album for her called Anyone Can See. Assorted new people that were getting big shot from record companies. Another dozen people off and on. I did a lot of production. It seems to me I was doing two or three albums a year.

Do you have a favorite song you recorded?

"Sugar Sugar" has to be the top of my list. It meant so much to me to break through and establish myself as a hit singer. "Sugar Sugar" is top of my list, and I love it very much. But they’re all my babies. I love them all.

How about anything you would just as soon forget?

"Yippy-Yay-Kay-Kay-Aye." One of the songs from the first Archies album. Kind of a country song I wasn’t into. I didn’t like that Jeff Barry song.

Was there anything you would have liked to have sung but couldn’t?

Just one is tough. "Happy Together." Or "Good Vibrations." I would have loved to have sung that.

A couple of years ago, you did an album called Favorites, where you recorded a bunch of people’s songs. How did you decide to do that, and how did you decide which songs you were going to record?

The record company RKO Unique gave me the opportunity to put out a Favorites themed album. I was producing videos and audios for maybe sixty or seventy 60s groups for a series called Legends Live, which is an audio-video series. I got to record all these groups… The Grass Roots, the Association, Lou Christie, Brian Hyland, Al Wilson. After working with all these people I realize I Liked their songs. So I recorded a bunch of sixties songs. I’m getting ready to do a Volume II of my favorite 70s songs.

When did you get back into touring?

Over the last few years I’ve returned to live performing. I’ve decided that something was missing in my life, and that was the getting out live and seeing the fans. And having some fun traveling around the country and the world. I’m doing this tour now with Andy Kim and Bo Donaldson & the Heywoods and the Ohio Express and Al Wilson and Alan O’Day. It’s called the Super Seventies tour. We’ll be performing in casinos and venues all over the country. This is a great tour, and they’re also talking about doing a PBS special at the MGM Grand.

Radio playlists are so regimented anymore. You used to be able to hear rock, soul, pop and country all on the same station, and that just doesn't happen anymore. Do you think that can inhibit new musicians?

It’s always been difficult to get on radio. No matter what. Hundreds of records come out a week. Only five or six are programmable to the stations. You’re really fighting an uphill battle. You really need the push of a record company or a manager or a great song. The fragmentation of the music market makes it so at least you know where you’re going. If you cut a country record, you know what radio you’re going on. MOR record, you go there. Pop, you go to the pop stations. It’s always been difficult, it will always be difficult. The one light I see is the internet and internet radio… which is going to give people access to 500 stations all over the world. Whatever they need on their car radios and things at some point. Maybe not this year, but five years from now most likely. The internet itself is helping groups establish themselves, with their own websites, their own sound clips and video clips. If you can drive traffic to you, get some publicity and get people to come take a look at you, there’s a better chance today than there was ten years ago when the industry was a closed unit. I just hope for the best for the new people. You go to MP3.com, you can see all kinds of stuff.

How would you like for people to see your music?

I would like them to say it meant something in their life. It had meaning and it enhanced their life in someway. It changed something. It brought them a smile or it made them get up and dance. ‘Sugar Sugar’ was one of the biggest dance records in the world, so I’m sure a lot of people danced to it. ‘Tracy…’ a lot of mothers and fathers named their kids Tracy. I meet a lot of Tracy’s now around 30-years-old. I would like people to just think back and think it contributed to the goodness of the world, and the positive stuff that came out of it. The year ‘Sugar Sugar’ was a hit, there was the Vietnam war and a lot of protesting and a lot of divisiveness. ‘Sugar Sugar’ was just this wonderful dance record, this happy little song that you could just kind of make anything out of it. That was the number one record of the year, 1969, in the era of Woodstock. So I was very fortunate to be a part of it. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Here's a student film (The Love Potion) made by Peter Tork circa 1962. The music was added by the person who uploaded the video. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

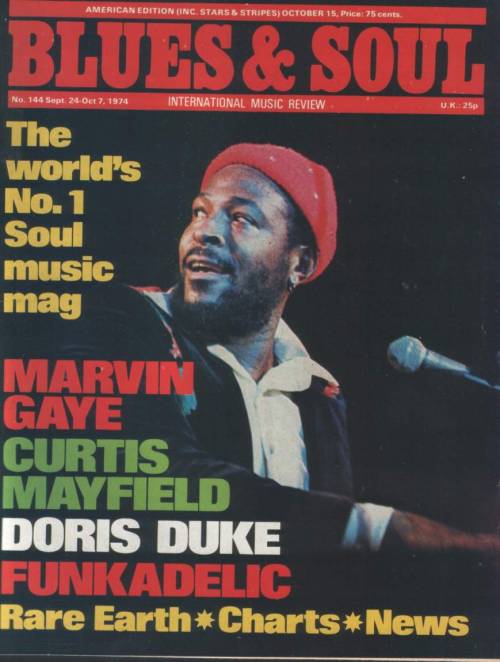

1981

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

John Lennon speaks to Howard Cosell in 1974 You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Kraftwerk 2001 You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

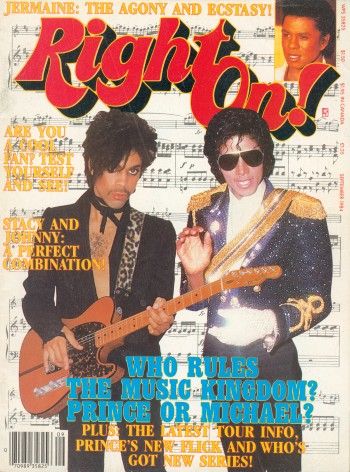

1984

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Typically great, enriching thread. Thanks!! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You're welcome. You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Roger Troutman interview in Tokyo You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Bob Harris interviews The Police on October 27, 1979 You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Phil Collins & John Goodsall (Brand X) 1979 interview You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Good thread !

Man that cover brings back memories. Years ago when i was doing time in juvenile hall, this issue of Rock and Soul was one of the few magazines that i had to read. I wore my copy out. Thanks for the memories man ! Rest in Peace Bettie Boo. See u soon. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

"Music gives a soul to the universe, wings to the mind, flight to the imagination and life to everything." --Plato

https://youtu.be/CVwv9LZMah0 | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

[img:$uid]http://i1142.photobucket.com/albums/n614/jamfanhot/th_Clipboard01.jpg?t=1351592387[/img:$uid]

Yesssssssssssssssssssss..lol Funk Is It's Own Reward | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

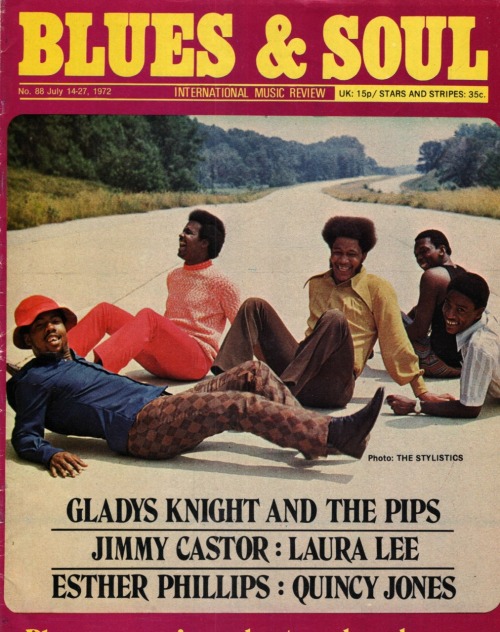

March 1972

Part 2

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

You can take a black guy to Nashville from right out of the cotton fields with bib overalls, and they will call him R&B. You can take a white guy in a pin-stripe suit who’s never seen a cotton field, and they will call him country. ~ O. B. McClinton | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

http

http :/

:/