I really enjoyed that interview with Andre Cymone.

It seems everyone from that time - Morris Day, Jimmy & Terry - they all have great nostalgia for their childhood in Minneapolis. Seems like it was a wonderful scene, and so great that young black kids were so into making music and encouraged by the community.

I'm copying here an article that MickeyDolenz posted in the non-prince forum thread "old stuff #3" - it has to do with this era that Andre is talking about.

Jimmy Jam was a DJ. Morris Day was a drummer. Prince was a kid with a huge afro. Before they changed popular music, Mom told them to turn that racket down.

Peter S. Scholtes

published: July 14, 2004

Summer, 2004. On the first of three nights at the Xcel Energy Center, Prince sits down on the floor in front of 19,000 people and reclines on some cushions. He pulls out the recent issue of Rolling Stone with his face on the cover ("Faith! Funk! Sex! He's Still Got that Red-Hot Magic") and begins thumbing through it mischievously as his band vamps on.

.

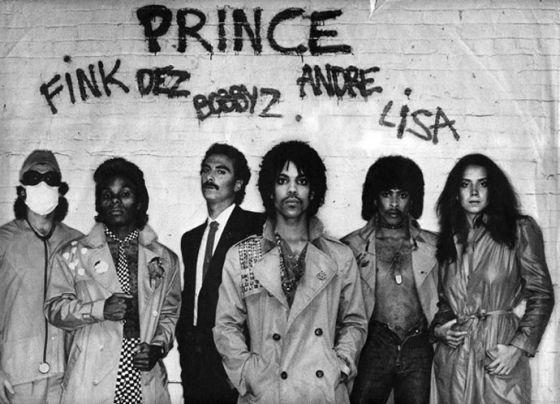

Inside he sees a photo of himself from a less confident time, looking skinny with a big Afro, wearing the kind of introverted half-smile you'd expect from a future librarian. On the same page is an article about an album that finds the man of the moment looking to his past--to the summers when he and his friends Morris Day, Terry Lewis, Jimmy Jam, and others were happy to play funk in backyards and basements on the north side of Minneapolis.

.

"Remember all the way back in tha' day/When we would compare whose Afro was the roundest?" Prince sings on "Reflection," the closing song on Musicology (NPG/Columbia). He rambles through the images of his youth: mirror tiles over the bed, posters and fishing nets on the walls. Then he concludes: "Sometimes I just wanna go sit out on the stoop and play my guitar/And just watch all/All the cars go by."

.

You can imagine that the street he's talking about is Russell Avenue North.

.

Summer, 1974. Prince is living in a basement in the home of his friend André Alexander (later André Cymone) on Russell, near Plymouth Avenue. His band practices in the damp room next door, on a red-painted floor crawling with centipedes and spiders. His second cousin Chazz plays drums, with André on bass, and André's sister Linda switching off with Prince on guitar and Farfisa organ. The boys are around 16, Linda 17. They call themselves Grand Central, having rejected "Phoenix" (from Grand Funk Railroad's 1972 album Return of the Phoenix) and "Soul Explosion." The name suggests Central High School in south Minneapolis, which Prince attends, as well as Grand Funk, and anticipates Graham Central Station, the new group led by Sly and the Family Stone bassist Larry Graham, who play O'Shaugnessy Auditorium in May of that year.

.

Prince sings low, like Sly. He covers Grover Washington and Carole King. All the musicians wear Afros. So does Morris Day, a shy and freckle-faced drummer who is friends with André. Before the year is out, Day is in the band.

.

In 1974, Terry Lewis is a champion sprinter at Minneapolis North High School. He plays bass in his own band, Flyte Tyme, named for a fusion song by Donald Byrd. Flyte Tyme are sort of a Parliament-Funkadelic to Grand Central's Family Stone. By the time P-Funk's mothership lands in '76, Terry and his friends are wearing space-age costumes and cramming as many as 10 musicians onstage, horns included. Cynthia Johnson, future voice of "Funkytown," sings and plays sax. Other recognizable names pass through the lineup: singers Sue Ann Carwell and Alexander O'Neal, drummer Garry "Jellybean" Johnson, and keyboardist Jimmy Harris III (later "Jimmy Jam," his DJ name at the Fox Trap disco).

.

Jimmy is two years younger than Terry and goes to Washburn High School. He later says Terry and Jellybean founded the group with him in '72, calling it "Wars of Armageddon," then "Soul Vaccination." By the mid-1970s, though, Jimmy has his own band, Mind and Matter. In fact, everyone seems to have a band, and live within a few blocks of Prince. Everyone knows him, though he keeps to himself. As Jellybean puts it to author Per Nilsen years later, "he was really never one of the guys."

.

You probably know what happened after that. Over the next 10 years, these young, gifted, black musicians went on to remake the sound of modern dance music. Recording his 1978 Warner Bros. debut entirely himself, Prince turned the keyboard-heavy rock of that basement on Russell Avenue into a career. He cherry-picked musicians from other bands to puppeteer the Time, a dapper new-wave funk band that pulled Morris Day out from behind his drum set. The group upstaged Prince more than once with their burlesque of Ragstock suits and mock-blueblood choreography, and even invented a new dance: "The Bird." Two members, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, became the first producer icons of pop, appearing in 1986's "Control" video with Janet Jackson, whose songs they wrote and recorded in Minneapolis.

.

"The early '80s in Minnesota was the new era for urban disco and funk," says Pete Rhodes, owner of BlackMusicAmerica.com. "Even Babyface, who was in a group called the Deele out of Cincinnati, sounded just like the Time. Everybody wanted to sound like the Time."

.

Today Morris Day is a benign icon of '80s self-regard. ("Don't you never say an unkind word about the Time," says Jay in Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, the 2001 movie. "Me and Silent Bob modeled our whole fucking lives after Morris Day and Jerome. I'm a smooth pimp who loves the pussy, and Tubby here is my black manservant.") Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis have more No. 1 singles to their credit than anyone besides Sir George Martin (10 for Janet Jackson alone).

.

Now, as the two producers close their Flyte Tyme studios in Edina to open a new one in Santa Monica--making the phrase "the Minneapolis sound" a permanent anachronism--it seems high time to take a closer look at the scene that started it all. Before the quiet leader of Grand Central brought home his first finished album from California, playing it for the Anderson family in their living room, live bands, not producers or DJs, defined the black music scene in the Twin Cities. While Grandmaster Flash and Kool Herc were throwing park parties in the south Bronx, Grand Central and Flyte Tyme were doing the same in north Minneapolis.

.

"We just made our own gigs," says Linda Anderson, Prince's bandmate in Grand Central. "We would go around and just play in neighborhoods, set up our equipment in the park and play, and have people gather round."

.

The mid-1970s found these bands getting serious--and seriously competitive. Terry and Prince started focusing more on music, less on sports. Prince quit basketball in his sophomore year; Terry suffered a football injury his senior year. Both ended up taking the same extracurricular course at Central High School, "The Business of Music," taught by a former piano player in Ray Charles's band. Terry wore a suit to class.

.

Flyte Tyme and Grand Central were only two of many groups at local battles of the bands. But their main rival, besides each other, was the Family, a jazz-funk group led by bassist virtuoso Sonny Thompson. Sonny went to North High School with Terry, but he was older and always seemed a step ahead of everybody else. He rocked a Jimi Hendrix look, wearing long leather jackets, pink and black, and could play any instrument well. He knew how to record backward on his four-track. He was also beginning to forgo other interests (karate and physics) to teach himself music theory. Terry played in Sonny's band before forming Flyte Tyme, and Prince often came by Sonny's house to borrow effects pedals. Like his peers, Prince idolized Sonny.

.

"It's funny, we were all playing at a community center, the Family and Grand Central," remembers Sonny Thompson. "I show up with this white suit on, and their whole band has the same suit."

.

The competition was friendly, though, and soon Prince and André were hanging out in Sonny's basement. "My mom, she would fry chicken, and we would just jam and eat," Sonny says. "That's how we grew up. I would have a band come over and rehearse in the front room, blocking the TV. Mom was cool with it."

.

When this scene was mythologized in the 1984 movie Purple Rain, the story left out one detail: helpful parents who weren't crazy. After Morris Day began drumming for Grand Central, his mom took over as the band's manager, pushing the group to become more professional. Grand Central became Grand Central Corporation, a company that owned each member's instrument. (When Prince left the band, he bitterly forfeited his Stratocaster.) André and Linda's mom Bernadette Anderson, who died last year, gave Prince a home. (She is known among hip-hoppers for providing an early space for parties at the Uptown YWCA.)

.

Prince's dad, a jazz man who couldn't have been further from Clarence Williams III's brooding brute in the movie, was at many of the early Grand Central shows taking pictures. By all accounts, the older generation of musicians took pride in the young upstarts. (Prince's uncle and Jimmy Jam's dad played on the first rock 'n' roll hit out of Minnesota, Augie Garcia's 1955 single "Hi Yo Silver.")

.

"It was more of a family-knit thing back then," says Walter "Q-Bear" Banks, a longtime programmer at KMOJ-FM (89.9). "Flyte Tyme, Grand Central, they were brothers that I grew up with. We played football on Saturday mornings over at Lincoln Field right off of Penn. Parents brung us Kool-Aid. If somebody did something wrong, there was a parent there to say, 'Hey, keep it in order.' Then that parent would call your parents and say, 'Hey, your son's out here clowning, and I had to spank him up.' And you got two spankings that day."

.

By 1974, the Family was being managed by longtime local activist Harry "Spike" Moss. For years, Moss had been a director at the Way, a storefront community center founded in 1966. Before the United Way cut the agency's funding in the '80s, the Way served as a kind of boys' club and outreach center for kids who in today's parlance would be called "at risk." It was also a locus of musical activity, hosting a succession of teen concerts and cordoning off Plymouth Avenue for festivals featuring all the young bands. ("To my knowledge," says Q-Bear, "it all started back at the Way.")

.

"Spike was a really active-in-the-community kind of guy," remembers Morris Day of Grand Central and the Time. "But I wasn't a Way type of person. A lot of tough kids hung out there, and I kind of shied away."

.

Linda Anderson says her parents wouldn't allow her to go to the Way, at least back when the Andersons lived in the projects. The agency's black-power philosophy was long established and controversial. When four blocks of Plymouth Avenue went up in flames in the July riots of 1967, police accused the Way of inciting the fire-bombers. But seven years later, Moss was up to something truly subversive: running a school of rock.

.

The Way Opportunities and Music School recruited organist Bobby Lyle and other musicians to teach kids about music--how to play it, how to read it, how to take it to the marketplace. "The one thing that we requested of all the students was that you give back to the next class," says Spike Moss. "So they'd come back and teach the next group coming through. As a matter of fact, the guy that taught Prince was Sonny Thompson. He was the baddest of all of them that came through the class."

.

Thompson describes Prince as a "sponge" rather than a student, soaking up knowledge from anyone he played with, and most musicians took pride in doing their thing without adult assistance. Jimmy Jam, who had started DJing at the Roller Gardens, remembers booking his band Mind and Matter at a downtown Minneapolis hotel himself. "That event drew something like 2,000 people, and pulled from the white clubs," he says. "With black and white, there's prejudice until there's green involved." The first big downtown club to open its doors to Jimmy and his friends was Uncle Sam's, which later changed its name to First Avenue.

.

Most black groups drawing black audiences were restricted to playing black-owned clubs. Thriving on the new bands, Jimmie Fuller's smoke-filled Cozy Bar and Lounge on Plymouth let them all play. (When the city bought the place out for highway expansion, the money went into launching the late Riverview Supper Club). There was also the Nacirema ("American" spelled backwards) over south, a "bring your own bottle" bar that kept booze in a cabinet to sidestep liquor laws.

"It was supposed to be a private club, all adult," says Sonny Thompson. "But once again, all the kids were playing. The police would raid it, too. We'd be playing, and next thing you know all these cops were on the stage with us."

.

For most of the kids, bars were a new world. Few of the musicians drank, smoked, or did drugs. "We were kind of even naive in that sense, I would say," says Linda Anderson. "Because, growing up, we weren't around people who got drunk or people who got high. So when we'd see that, we'd say, 'Look at that!'"

.

By 1976, Prince couldn't wait to escape this scene. One of his first original songs was called "Go to New York" (it contained the lyric "Sitting here on the purple lawn"). But he never really left Minnesota, and over the past three decades, he seems to have tried to recreate the feel of his formative years on Minneapolis's north side.

.

Prince has hired and rehired old friends, including Sonny Thompson, who recently played at Paisley Park with the Legendary Combo. He named an unrelated '80s new wave band the Family, and titled the Time (who were recent surprise openers for Prince on the second night at the Xcel) in obvious homage to Flyte Tyme. From Myst, a leggy black female trio he caught one night at the Nacirema, he took inspiration for Vanity 6, who debuted at the same bar. The three sisters in Myst eventually formed Best Kept Secret, who were also invited out to Paisley in June.

.

Prince might miss the sense of community that comes from nobody being a star and everyone wanting to be one. If that's the case, of course, there's no going back. He's still on the stoop somewhere playing his guitar. But all of the cars are in valet parking.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable

will ALWAYS think of

will ALWAYS think of  like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.

like a "ACT OF GOD"! N another realm.  Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator