There is a bar. It is no ordinary bar. The bar is located at the intersection of time, memory, and love, and is run by three black, female creatures: a mermaid, a unicorn, and a ‘divergent’. The bar is home to all those people who can’t identify with the present. The bar can be found in a galaxy far away, and maybe in our reality, too; in any case, it can be found in the sci-fi movie Bar Star City (release date TBA), written by scriptwriter, author, and Afrofuturist Ytasha Womack. Womack describes the movie as a fusion of the television series Cheers, the strange dream you had last night, and the electronic hip-hop producer Flying Lotus. The movie is what you would characterise as Afrofuturism.

Ytasha Womack is not the only one to take up Afrofuturism in recent years. Musicians like Beyoncé, Solange, and Janelle Monae pursue its aesthetics with metallic future uniforms, and a reinterpretation of the Sapeur suit (which emerged in DR Congo in colonial times, ed.). The award-winning author Ta-Nehisi Coates currently writes the scripts for Marvel’s Black Panther comic books that were adapted and released as a motion picture this February. Black feminists practice Ugandan magic and conjure up spirits from concrete buildings. The ad photographer Osborne Macharia, who resides in Kenya and is a 2017 Cannes Lions gold winner, has even made Afrofuturism his trademark. And within the last two years, several Afrofuturist conferences have been held in Europe and the US.

Afrofuturism is a genre and a way of thinking that blends Afro-culture, science fiction, magical realism, technology, and traditional African mysticism. It takes many forms, and tells many different stories, but one common feature is that Afrofuturists fight for equality and black people’s right to a place in the future. A place and a future that must not be defined by whites. Afrofuturism is a language of rebellion.

“Through time, very few black men and women have appeared in science fiction. It is not until recently they are being incorporated in the genre and that those ideas are being accepted by mainstream culture,” Ytasha Womack says. Womack is the author of The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, a book about Afrofuturism that has contributed to her status as a modern expert in the field.

”That is not just an exciting development, it is an important one. Especially for oppressed people and cultures, who have not been able to tell their own stories. Afrofuturism inspires your imagination. It transforms perspectives and creates hope that enables us to fight for a better society today and in the future,” says Womack.

New Afrofuturist scenarios are drawn up, and light sabres are sharpened. An expansion of the cultural future universe is taking place. But why use science fiction as a device to create a more equal present? And what does it do to people, not being able to see themselves in the future?

A NEW GENERATION OF FUTURISTIC WARRIORS

Afrofuturism is not something entirely new. The word comes from Mark Dery’s essay ‘Black to the Future’ from 1993, and the epistemology dates back even further. There are many kinds of Afrofuturist tales. Some are dystopian, others utopian. One of the first known Afrofuturists in the West was the jazz musician Sun Ra who was part of the Chicago jazz scene in the 1950s. He made experimental fusion jazz, mixing different genres and composing ‘the sound of the future’. But it wasn’t just his sound that was groundbreaking within the Afrofuturist genre. He broke into the future with his stage performance, his clothing, and not least his conviction. Sun Ra believed that he came from the planet Saturn, to which he allegedly returned when he ‘left Earth’ in 1993. Sun Ra did not believe that it was possible to achieve racial equality on Earth; a society without racism could only be found on another planet.

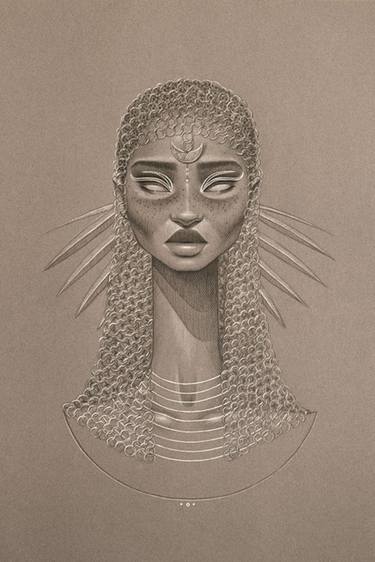

The word Afrofuturism is originally American and mainly referred to Afro-American artists. But today, several African artists are associated with the wave, too. One of them is the Kenyan photographer Osborne Macharia whose photographs have been nominated and awarded at the prestigious Cannes Lions advertising festival. Afrofuturism is particularly apparent in his aesthetics. Macharia’s colourful pictures of smartly-dressed grandfathers from Kenyan shanty towns, and cyborg-like women, have made their rounds on the internet several times. He is one of the few Afrofuturist artists who can make a living from his art, and he has even managed to make it commercial. Last year, he and a handful of other African creatives were chosen to make Absolut Vodka’s latest campaign, ‘Absolut One Source’.

“Afrofuturism is an interpretation of the kind of future we want Africa to be associated with. It is of course about aesthetics and entertainment, but it just as much about highlighting issues that are important to Africa as a continent. For me those issues are discrimination, inclusion, gender abuse, ivory poaching, female genital mutilation, care for the elderly, and conflict resolution. Lately I have also focused on conservation. I want to show what Africa really looks like, I want to portray how magical the continent is,” says Macharia:

”I believe Afrofuturism has the ability to motivate a new generation of futuristic warriors.”

THE BLACK TRAUMA MUST BE HEALED

Beautiful pictures, wild stories, new communities, and new visions of the future grow as Afrofuturism develops. This is part of the reason why Afrofuturism is not just an aesthetic style of art, according to Ytasha Womack.

“Talking about the future fundamentally changes you. It transforms the present. It expands your imagination and you start to imagine new societal scenarios,” she says. “The power of imagination creates hope and reminds you that society isn’t permanent, but always in flux: that you, as a person, possess the drive and the power to influence society,” she explains. “But for many black-bodied people that means they have to push past the idea that they don’t think they have any influence on their own future,” Womack says.

Last year, a black female politician named Ingrid LaFleur ran for mayor of Detroit. Two of her platform issues were pulling Detroit out of the mire of poverty and improving conditions for the black citizens who are still left high and dry everywhere. And she wanted to do this with the aid of Afrofuturism. She held workshops for the locals in Detroit where they had to find their inner superhero. She gave parties where African techno and Afro-punk was played to inspire a sense of community and connect people to their roots. She was not elected, but her mission is not over. She still works with the local environment as a curator and artist in Detroit.

“There has been a very narrow definition of blackness in the U.S.,” Ingrid LaFleur says.“A narrative that goes back to the transatlantic slave trade. For hundreds of years, the only thing black people were meant to do was serving the whites; in their houses, their restaurants, and the missions” she explains. “And I honestly I don’t think it has changed. It is still affecting our policies; our voices are constantly being negated, ignored and silenced. We are still dealing with police brutality and we are still being targeted. And that affects how we see our future,” she says.

Some young blacks don’t expect to live beyond 30, and they believe that going to jail is inevitable. Many black girls expect to become young mothers, because that is what happened to their mothers and grandmothers. This is the way society views black bodies, and this, unintentionally, influences the way they see themselves – “and that makes it difficult to dream of a different future. But I believe that Afrofuturism has the ability to heal traumas that live in black bodies,” LaFleur says.

“The ideas of race and hierarchy are created by man. Gender roles and norms are created by man. It is technology. None of it has been that way since the dawn of time. They are structures of society that we continue to support if we don’t believe that we have the ability to change them. That is why it is so important to let our imagination and hope flourish,” Ytasha Womack states.

Historically, hope and the power of imagination have played an important role in the Black Power Movement: “When you look at the African experience in the US there has always been a narrative of hope. Barack Obama talked about hope. Jessie Jackson talked about hope. Gospel songs talk about hope. Hope and imagination save lives,” Womack says.

”But it is not just about hoping for a better future,” she says, and continues: “People of African descent have had to use their imagination as a statement of existence. We had to imagine a past, because it has and still is difficult to find reliable information. We have to imagine the present because the reality presented to us by the media does not reflect the diversity of the culture we are part of. We have to imagine a future, because very often we are not represented in the future dictated by mainstream culture. We are not using our imagination to imagine things that aren’t real, we are using it to reinforce reality.”

SCIENCE FICTION AS A CULTURAL-POLITICAL INSTRUMENT

It is not the first time science fiction has been used as a cultural-political instrument, Niels Dalgaard explains. Niels Dalgaard holds a PhD in Nordic Literature and is an expert in science fiction, a writer, and the editor of Proxima, the Danish journal of science fiction.

”The feminist utopian tales of the 1980s represent a good example of how science fiction has been used as a cultural-political tool. At the time, they took a genre that was considered dead – hardly anybody had written utopian tales for a hundred years – and not only brought it back to life, but developed it further,” Dalgaard says.

With feminist utopian tales – in themselves a contrast to the male-dominated, anti-utopian literary trend of the day – a world was sketched out where equality was possible. Where, for example, women were in power, and the divine feminine ruled. A society was depicted that was considerably better than the one we lived in, but still with room for improvement and development. A dynamic utopia.

”It is an example of a literary wave that brought the world forward,” Dalgaard says.

”Utopian tales are not like the private wishful fantasy of winning a fortune in the lottery. No, utopian tales show us collective dreams and specific ideas about how we would like society to be. Generally, science fiction is the only genre whose basic premise is that the world does not stand still. Then you can discuss whether that is a good or a bad thing, whether you can influence it, or events just pass you by. And this can be unfolded as a critique of power, an enthusiasm for technology, or a fear of the unknown. But the recognition that change is a basic condition is always there,” Dalgaard explains.

Scientists have searched for inspiration for their work in science fiction writings, too. Writers and scientists enter into a dialogue. For example, the Afrofuturist writer Deji Olukotun made a presentation last year together with astrophysicist Lucianne Walkowics; the subject was solar flares, a phenomenon they both have explored in their work.

”Science fiction can raise questions that science cannot without colliding with its own rules. Many scientists are also writers of science fiction, but often, they do not write about their own main area of expertise, but about a neighbouring area where their knowledge does not impede their imagination. You can be bold when you toss off hypotheses, but you must be rigorous when you put them to the test,” Dalgaard says.

A WHITE GENRE

But finding a place in science fiction is still not easy if you are black, Ytasha Womack points out.

“The biggest problem is that the realm of science fiction is seen as a space for intellectualism. And there is a resistance to engage people of colour in that conversation,” Womack says, continuing: “There are still black artists negotiating with their ability to create their own image, because they are told it is not sellable. We live in a society where everything is commoditised, which does not always have to be a bad thing, but when it starts to inhibit people from mirroring themselves it becomes problematic.”

The world of science fiction is generally known to be rather closed in on itself. Readers are often writers, too. There are countless virtual and physical forums for the discussion of science fiction movies and books in particular. But as Ytasha Womack points out, that world is very much dominated by white men, Niels Dalgaard explains.

”To most people in English-speaking countries, the genre was founded in the 20th century in the environment of small American science-fiction magazines. The environment surrounding the magazines was seen as dominant and trend-setting. This created a strong spirit of unity, and a network. And those settings were, and are, very much dominated by white males. But science fiction has been written in different contexts, too; the institutions just haven’t paid as much attention to it,” Dalgaard says.

There is no doubt that there have been very few black commercial writers of science fiction, and Dalgaard thinks it is a good and interesting thing that this has started to change – “reading science fiction written by writers from other cultures leads to entirely different and thought-provoking visions of the future,” he says. But compared to other literary genres, he actually believes science fiction has been characterised by a degree of diversity.

”I don’t think science fiction has been particularly discriminating. Again, I can mention the example of the 1980s where feminists had a good grasp of the genre. And since it has became easier to publish books yourself, there are more different kinds of stories and writers today than 30 years ago,” Dalgaard says.

”Generally, there is a lot happening with respect to inclusion within science fiction today. With respect to gender as well as race, and with regard to subject matter, stories, and the genre community,” he says.

STILL PULP FICTION

Ytasha Womack and Osborne Macharia are pleased with the attention Afrofuturism has received from mainstream media, production companies, and publishers in recent years.

“I think it is great that Afrofuturism is getting more attention. We can thank social media for that. They have enabled people who are interested in Afrofuturism to find each other, connect, and create new communities,” Womack says. The very fact that Marvel’s Black Panther movie has been made is just one of many examples that there is a large and dedicated audience for Afrofuturism – “There is an audience for afrofuturistic and diverse film, comics and litteraure. That is no longer a question. The Black Panther movie is coming out due to fans asking for more diversity,” she says.

”But we still need the Afrofuturistic future, the hope, the fantasy and combination of science, technology, art and mysticism to be taken seriously by [cultural and scientific, ed.] institutions. In the West we are used to separating all subjects. I think it will benefit us all if we started to integrate the different fields more. So that you can learn from Afrofuturism,” Womack says.

”It is paramount that institutions continuously dare to bet on Afrofuturism,” Osborne Macharia says. Macharia has been lucky to hit a commercial nerve and be able to earn a living as an Afrofuturist photographer. But for most others, this is not the case. Many Afrofuturist artists have to publish and produce their work themselves, and the genre is still not taken entirely seriously. But that is a general problem for science fiction, Niels Dalgaard says.

”I see a growing number of non-genre writers who use genre techniques and borrow from science fiction. But writing science fiction still isn’t respectable. It is not as classy or serious as other kinds of literature – it is ‘pulp fiction’,” Dalgaard says. This is indicated, for instance, by the fact that publishers don’t want books labelled as science fiction, even if the writers are using science-fiction techniques, he explains.

“The imagination is easy to ridicule. It is one of the first things you reject when you are in a crisis. It is not pragmatic or practical. But really, it is the backbone of our existence and resilience,” Ytasha Womack says. “It is the fuel of innovation,” she adds.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator