They would profess themselves to be horrified by homophobia. But they all conspire to keep their dream factory pumping out images of idealized heterosexuality, fronted by celebrities that they represent and direct and produce living public lives of the same.

Hunter’s story may look vintage; it remains depressingly current.

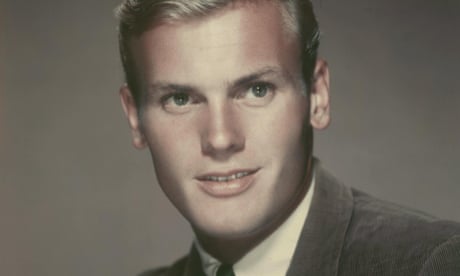

In one interview after he came out, Hunter mused that “the boy next door label” Hollywood gave him, as it built his image as a classic fifties prettyboy heartthrob, was merely a selling label: “They grind it out like a sausage factory.”

Hunter knew he was a product, just as the actors know they are products. Being openly gay today may not get you thrown off the production line as it did in the 1950s, but it may not get you the best window display.

Hunter was so anguished about his life of enforced silence, and by being a naturally private person—and where those two things intersect is a fascinating netherland—that it’s pretty amazing he did come out. But, as he said, “Heck, I’m an old man. This is my life.”

He was raised, he recalled, in a not-happy home. His father abused his mother. His mother preferred his brother. He was raised Catholic. Movies were Hunter’s escapism, or Art Gelien’s escapism as he was then known.

He heard the words “fairy” and “queer” as insults. He pushed what he was from his mind; he didn’t want to be different. His story could be a story of today, the story of young gay kid eternal. His looks caused such a stir at school with girls he sought out empty classrooms to hide in. He revealed all at confession, was told how bad being gay was, and fled from the church.

An early, pre-Hollywood love was horses; the same love would sustain Hunter long after Hollywood’s lights had dimmed. There, at a stables where a young Hunter worked, an actor named Dick Clayton came one day. He never made a move on Hunter, but he led him to Hollywood.

“On TV shows Hunter was hailed ‘Hollywood’s most eligible bachelor.’ Hunter, as he said years later, was in an industry ‘where you are rewarded for being someone you are not.’”

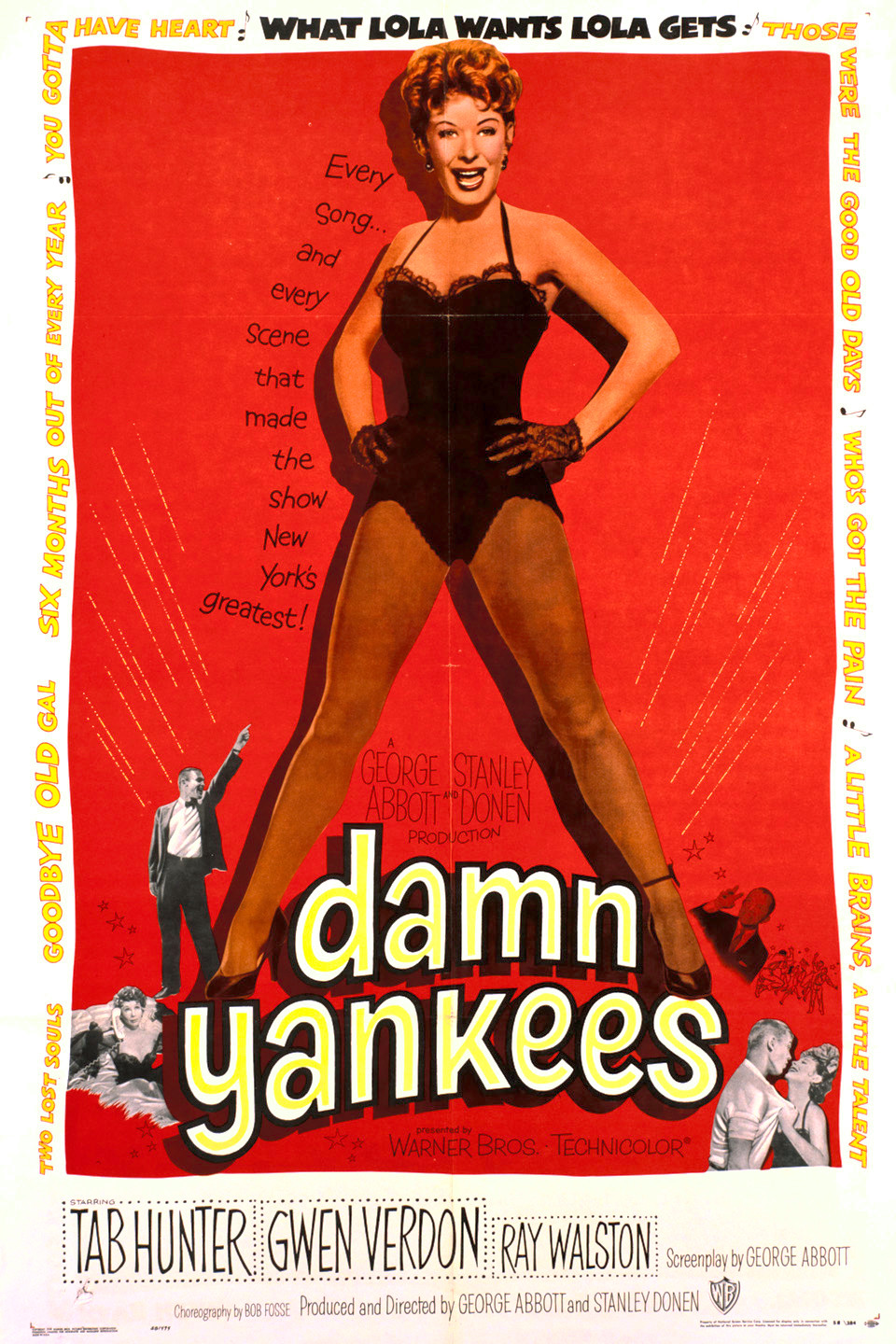

Enter Henry Willson, the agent who had all the hunks on his books at the time, including Rock Hudson. He put Hunter into movies where his clothes were either swimming trunks or military duds. He was a clean-cut hero.

Off-screen Hunter fell in love with ice skater Ronnie Robertson; the ice-skating chiefs of the time warned Robertson to keep Hunter away from watching him compete. Robertson defied them. But their relationship was conducted in secret. This was a time when homosexuality was considered a mental illness, and when exposure for them would have meant professional ruin.

On TV shows Hunter was hailed “Hollywood’s most eligible bachelor.” Hunter, as he said years later, was in an industry “where you are rewarded for being someone you are not.”

Early on, Hunter survived a gay scandal; when Hunter chose to be represented by Clayton, he thought Willson had passed the story of his arrest at the 1950 gay party to gossip rag Confidential—both as revenge, and as a sacrificial lamb (Confidential had been planning an exposé of Hudson). The magazine called the 1950 gathering a “limp-wristed pajama party” (which sounds great fun to me), and Hunter was sure his career was over.

It wasn’t. His studio boss Jack Warner told him “Today’s headlines are tomorrow’s toilet paper.”

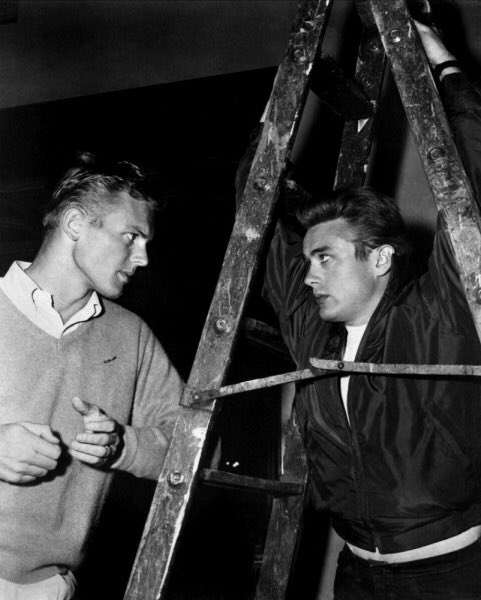

Hunter did what was required. He went on dates with Natalie Wood and other actresses, dates that were photographed. As soon as the cameras stopped clicking, she went off to see her real date Dennis Hopper, and Hunter went off to see Anthony Perkins who he was dating back then. One of his girlfriends, Etchika Choureau, recalled that they really liked each other but that she didn’t want a show marriage, and neither did he.

Hunter said at the time, that he felt if you were with a man you’d be sinning, if you were with a woman you’d be lying.

It sounds a gilded cage, an enforced hell, and an embraced and accommodated hell. He wanted fame. This was the price. But even if you weren’t famous, in those days, a similar set of choices were on offer.

As it turned out, Hunter overplayed his hand, stood up to Jack Warner, then realized, too late, it was “career suicide.” Cheesy films—terrible films—followed. He became a joke, and then he played off that image in Polyester and Lust In The Dust. He fell in love with Glaser.

Still, Hunter wouldn’t come out, even as Ellen, George Michael and others did. In the documentary, Portia de Rossi says how hard today it is for out actors to be out, how nervous she was to do it. Noah Wyle says he knows several stars who won’t come out.

Glaser offered Hunter the opportunity to meet the person he wanted to spend the rest of his life with. Glaser noted that Hunter was happiest mucking out and riding his beloved horses. When his old movies came on TV, said Glaser of his partner, Hunter flicked the channel as if surfing past a dog-food commercial.

Hunter recalled seeing Anthony Perkins years later, married and with a family, before he died of AIDS. “His choice was right for him,” says Hunter. “It was who he was, or maybe who he wanted to be.”

And in that tortured and perceptive deconstruction, Hunter hit on all the warped mechanics of how the closet works in and out of Hollywood.

But what is Hollywood scared of? What won’t it test? What scares it as much in 2018 as it did in 1950? It’s scared that the film-going audience won’t buy their leading woman or man kissing an opposite-sex love interest if they know that leading actor is gay or lesbian, or trans.

That lack of courage means that audiences remain unchallenged. It also underestimates their powers of suspended disbelief, which a decent actor is supposed to draw on.

It also means that less LGBT films are made by mainstream Hollywood. Even more cowardice, ignorance and a lack of courage. And sure, actors will come out in dribs and drabs, and yes, LGBT movies will come out in dribs and drabs, and other opinion pieces will question whether a turning point has been reached, whether we are progressing. We aren’t. Hollywood isn’t, and the LGBT people working there at celebrity and non-celebrity levels are complicit in perpetuating this shameful lack of progress.

They should all watch the Tab Hunter documentary, and they should read his words. He never sought sympathy for living in the closet, or why he lived in the closet, or what its effects were. He seems a practical person. Debbie Reynolds calls him “grounded,” and he does seem plain-speaking, and plain-thinking.

In an interview last year, Hunter said, “If I had come out during my acting career in the 1950s, I would not have had a career. Not much in Hollywood has changed in 60 years. I really didn’t talk about my sexuality until I wrote my autobiography.

“There still isn’t a romantic lead in films who is actively working who has come out as gay. Film actors today still fear that coming out would damage their career.”

“My film career had long since been over by then. I believe one’s sexuality is one’s own business. I really don’t go around discussing it. Call me ‘old school’ on that topic.”

Tab Hunter made his decisions, he lived with the results of them, and ultimately he found love and sustenance with another man. And he came out, just as so many LGBT people do; just as Harvey Milk rightly recommended as the key act of LGBT liberation and declaration.

And Hunter went further: he told the truth not just about himself, but also about Hollywood.

“There still isn’t a romantic lead in films who is actively working who has come out as gay,” Hunter said in that same 2017 interview. “Perhaps there has been on TV, stage and in different arenas in the entertainment business, but not a major movie star. Film actors today still fear that coming out would damage their career.”

Yes, Hunter is right: they still fear that. Wouldn’t it be grand if part of Tab Hunter’s legacy was the shattering of the Hollywood closet? He did it and found out, in the best way, that it was better late than never.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator

It was not until 2005, though, that Hunter came out publicly, using his memoir (co-written by Eddie Muller) to pre-empt another tell-all that was also in the works. Its opening words – “I hate labels” – reflect Hunter’s discomfort with an industry hellbent on typecasting him as the Sigh Guy, the Boy Next Door and “the even more ludicrous Swoon Bait”. But, in its Inside Baseball approach to revealing the inner workings of Hollywood before, during and after the studio era, it is a remarkably insightful, confident account of and by one of Hollywood’s first gay movie stars, a label by which the famously self-effacing Hunter would surely be chagrined. In death, though, Tab Hunter’s legend won’t fade. The 2015

It was not until 2005, though, that Hunter came out publicly, using his memoir (co-written by Eddie Muller) to pre-empt another tell-all that was also in the works. Its opening words – “I hate labels” – reflect Hunter’s discomfort with an industry hellbent on typecasting him as the Sigh Guy, the Boy Next Door and “the even more ludicrous Swoon Bait”. But, in its Inside Baseball approach to revealing the inner workings of Hollywood before, during and after the studio era, it is a remarkably insightful, confident account of and by one of Hollywood’s first gay movie stars, a label by which the famously self-effacing Hunter would surely be chagrined. In death, though, Tab Hunter’s legend won’t fade. The 2015