Why and how to read a

cow or bull

Knowing behavior patterns, especially of bulls, may help

reduce injuries and might possibly save your life. Reading

behavior can also help you improve care.

By Jack Albright

Hoard's Dairyman Magazine

The author is professor emeritus of animal science and veterinary medicine, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind.

Automation, considered by some to be detrimental to the husbandry and welfare of animals in intensive units, needs to be reconsidered. The time saved, together with reduced work and drudgery, should release workers for more human-animal interactions, thus allowing better care. Yet, there are many instances where farm staff come into one-on-one contact with animals. Are they prepared?

For as long as cows have been milked, there has been the art of cow care that results in more milk from healthier, contented cows. It has been recognized that the dairy cow’s productivity can be adversely affected by discomfort or maltreatment. Alert handlers have the perception and ability to read body language in animals.

For example, healthy calves, cows, and bulls will exhibit a good stretch after they get up, then relax to a normal posture. Yet, higher rates of standing, oftentimes with an arched back and with their head and ears lowered, is taken as a sign of discomfort or discontent in studies of cow and calf confinement.

Cattle under duress show signs by bellowing, butting, or kicking. Behavioral indicators like these are always useful signs that the environment needs to be improved. In some cases, the way animals behave is the only clue that stress is present.

You can get clues to a cow’s mood and condition by observing the tail. When the tail is hanging straight down, the cow is relaxed, grazing, or walking, but when the tail is tucked between the cow’s legs, it means the animal is cold, sick, or frightened. During mating, threat, or investigation, the tail hangs away from the body. When galloping, the tail is held straight out, and a kink can be observed when the animal is in a bucking, playful mood.

Dealing with bulls . . .

By virtue of their size and disposition, bulls may be considered as one of the most dangerous of domestic animals. Farm procedures should be designed to protect human safety and to provide for bull welfare. Everyone who comes into contact with bulls should recognize the various body postures of threat and aggression. This is the only way a person can stay mentally and physically ahead of the bull.

If cornered by a bull, it is best not to move too fast, but to back away from the bull’s flight zone which is about 20 feet in range. While moving away from the bull’s flight zone, you should watch the bull at all times until you get to a fence, crawl space, or other safe retreat. Turning and running invites being chased. Not as likely, but the same can be said for aggressive fresh cows with their newborn calves as they, too, can attack and maul.

Understand postures, threats . . .

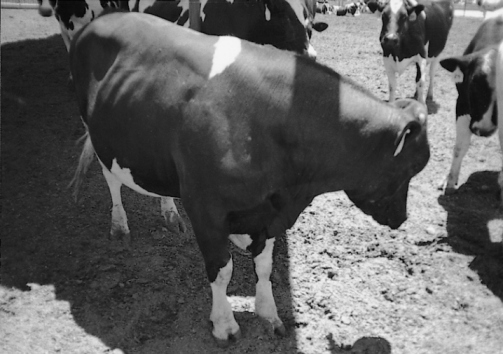

There are certain major behavioral activities related to bulls. These are threat displays, challenges, territorial activities, female seeking and directing (nudging), and female tending. These activities tend to flow from one to another. Threat displays are a broadside view (Photo 1). This posture is observed when a person or another bull invades its flight zone.

PHOTO 1. BROADSIDE THREAT DISPLAY is a warning that a human has invaded his flight zone.

The threat display of the bull puts him in a physiological state of fight or flight. The threat display often begins with a broadside view with back arched to show the greatest profile, followed by the head down, sometimes shaking the head rapidly from side to side, protrusion of the eyeballs, and erection of the hair along the back.

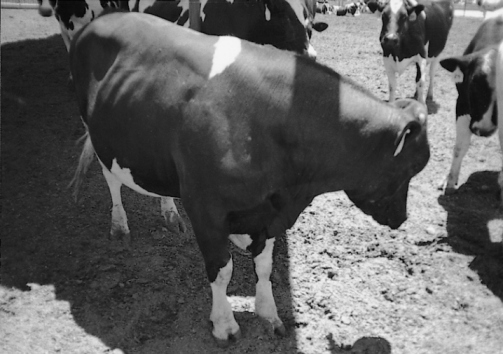

The direct threat is head-on with head lowered and shoulders hunched and neck curved to the side toward the potential object of the aggression (Photo 2). Pawing with the forefeet, sending dirt flying behind or over the back, as well as rubbing or horning the ground are often components of the threat display (Photo 3). If, in response to the threat display, the recipient animal advances with head down in a fight mode, a short fight with butting of horns or heads ensues. If the recipient of the threat has been previously subdued by the animal, he will likely withdraw with no further interaction.

PHOTO 2. DIRECT THREAT IS HEAD-ON with head down and shoulders hunched and neck curved towards the threat.

PHOTO 3. JERSEY BULL PAWING the ground. In the foreground, another bull is seeking out potential females in estrus.

While a bull is showing a threat display, if an opponent such as another bull (or person) withdraws to about 20 feet, the encounter will subside, and the bull will turn away. If not, the bull will circle another bull or animal, drop into the cinch (flank) body position, or start with head-to-head or head-to-body pushing.

At the first sign of any of the above behaviors, humans should avoid the bull and exit rapidly, hopefully via a predetermined route.

With the advent of artificial insemination, the bull initially left many dairy farms. With poor estrus detection and difficult breeding cows, the yearling bull has made a come back as a "clean-up" bull. While observing cows in larger herds in the Southwest U.S., I found as many as seven yearling bulls in a group. Rightfully so, at the first sign of meanness, a bull was sent on a one-way trip to the butcher.

Many people lack the background, attitude, and precaution of dealing with dangerous bulls and fresh cows; therefore, additional training on bull/cow behavior is needed. It is wise to respect and be wary of all bulls, especially dairy bulls, as they are not to be trusted. Each bull is different, and any bull is potentially dangerous. He may seem to be tame, but, on any given day, he may turn and severely injure or perhaps kill a person, young or old, inexperienced or experienced.

Bulls become defensive when a cow is in heat and needs to be removed from "his" group or moved with the group to the holding pen for milking. Never handle the bull alone, and never turn your back on a bull. To move cattle or to appear larger and to protect oneself, carry a cane, stick, handle, plastic pole with flap, or a baseball bat. For further information about bull behavior and handler safety, refer the book by to Albright and Arave, "The Behavior of Cattle," CAB International, 1997, or many of the older dairy textbooks.

In addition to bulls, you must be careful around certain steers, heifers, and recently calved cows protecting their calves. Some animals are different and do not follow the threat display behavior previously mentioned. Be careful of following behavior, walking the fence, bellowing, a cow in heat, and the bull that protects the cow, thereby attacking the handler. Remember, an animal’s first attack should be its last, and it should be sent to the slaughterhouse; see Hoard’s Dairyman, November, 1998, page 787.

Animal care has a profound effect on their temperament, and this is not always taken into consideration. For example, bull calves should never be teased, played with as a calf, treated roughly, or rubbed vigorously on the forehead and area of the horns. You should stroke under the chin (rather than on top of the head) as an appeasement, taming, grooming-like behavior. This is essentially the way cattle groom each other.

Learn to be a good observer . . .

Observation of dairy cattle has been going on for centuries and helps to raise knowledge and improves husbandry techniques. A more logical approach to the study of cow behavior and training is now advocated, linking it with commercial operations. Time saved through today’s automation should be invested in observing animals. A knowledge of normal behavior patterns provides an understanding about cattle and results in improved care and handling that will achieve and maintain higher milk yields, worker and animal comfort, and welfare.

The National Institute for Animal Agriculture, formerly known as the Livestock Conservation Institute, Bowling Green, Ky., has prepared an excellent training video entitled, "Understanding dairy cattle behavior to improve handling and production" (Hoard’s Dairyman, April 10, 1993, page 336). Dairy cattle must fit in well with their herdmates, as well as their handlers. For those who like to work with dairy cattle, proper mental attitude must blend in with skillful management and humane care in today’s highly competitive, technological, urban-based society.

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable Report post to moderator

Report post to moderator