| Author | Message |

Former 49er head coach Bill Walsh dies **it's extremely long, but I'm sure football fans will enjoy his history and contributions to the sport**

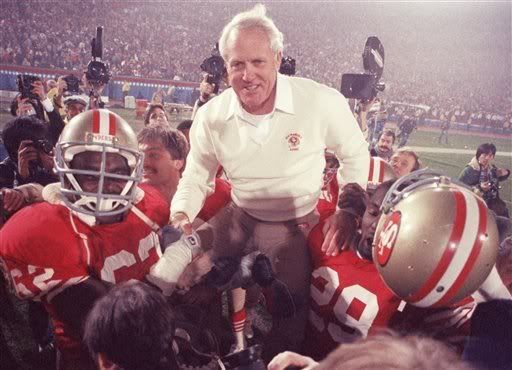

Former 49er head coach Bill Walsh dies Tom FitzGerald, Chronicle Staff Writer Monday, July 30, 2007 (07-30) 11:50 PDT -- Bill Walsh, the imaginative and charismatic coach who took over a downtrodden 49ers team and built one of the greatest franchises in NFL history, has died at the age of 75 after a long struggle with leukemia, it was announced today. A master of using short, precisely timed passes to control the ball in what became known as the West Coast offense, he guided the team to three Super Bowl championships and six NFC West division titles in his 10 years as head coach. The 49ers had been wrecked by mismanagement and unwise personnel decisions under former general manager Joe Thomas when owner Ed DeBartolo Jr. cleaned house in 1979. Walsh, who had led Stanford to two bowl victories in two seasons as head coach, took a 49ers team that had finished 2-14 in 1978 and built a Super Bowl champion in just three years. It was one of the most remarkable turnarounds in professional sports history. His teams would win two more Super Bowls (following the 1984 and 1988 seasons) before he turned the team over to George Seifert, who directed the 49ers to two more championships ('89 and '94). Walsh set the foundation for an unprecedented streak in the NFL of 16 consecutive seasons with at least 10 wins. He had a knack for spotting talent and then developing that talent to its fullest. His touch was particularly deft when it came to quarterbacks. He drafted Joe Montana in the third round in 1979 and acquired Steve Young, then a backup with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, in 1987 for second- and fourth-round draft choices. Both were elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. At his own Hall of Fame induction in Canton, Ohio, in 1993, Walsh revealed he nearly didn't make it to the end of his second season in San Francisco. "In those first three years, we were trying to find the right formula," he said. "We went 2-14 that first year (1979). The next year we won three and then lost eight in row. I looked out of the window for five hours on the plane ride home from Miami after the eighth straight loss, and I had concluded I wasn't going to make it. I was going to move into management." He changed his mind and finished the season, a 6-10 year. The 49ers gave notice of things to come in a late-season game against the New Orleans Saints at Candlestick Park. Trailing 35-7 at halftime, they thundered back to win 38-35 in overtime. At the time, it was the biggest comeback in NFL history. But the real magic was yet to come. After losing their first two games in 1981, the 49ers would win 15 of their next 16 games in a methodical yet astonishing march. Behind Montana and wide receivers Dwight Clark and Freddy Solomon and a defense led by linebacker Jack "Hacksaw" Reynolds, pass rushing whiz Fred Dean and a secondary that started three rookies -- Ronnie Lott, Eric Wright and Carlton Williamson -- they became the first NFL team in 34 years to go from the worst record to the best in just three seasons. To do it, they had to shock the Dallas Cowboys 28-27 in the NFC Championship Game. They won it on Montana's scrambling 6-yard pass to a leaping Clark with 51 seconds left. The play, dubbed "The Catch," is the most celebrated moment in Bay Area sports history. "That was a practiced play," Walsh said. "Now, we didn't expect three guys right down his throat. That was Joe who got the pass off in that situation, putting it where only Clark could come up with it." Walsh showed his zany side two weeks later in Pontiac, Mich. Arriving before the team, he borrowed a bellman's uniform at the hotel and collected the players' bags at the curb, even holding out his hand for tips. His players didn't immediately recognize him, including Montana, who got into a brief tug-of-war with him when Walsh tried to grab his briefcase. In Super Bowl XVI, the 49ers built a 20-0 lead but needed a memorable goal-line stand in the fourth quarter to hold off the Cincinnati Bengals and win 26-21. Pro football in San Francisco would never be the same. Walsh and his players were stunned by the reception they received when they returned to San Francisco. "There was a suggestion of a parade for us," Walsh said years later, "and I remember thinking that with the general fatigue I was reluctant to put the players through something that might be just a few people waving handkerchiefs on the street corner." Instead, the city had basically been shut down for a celebration by more than half a million people, cheering San Francisco's first NFL champions as they were driven down Market Street. "It was just an overwhelming experience, the realization that millions and millions of people had been following us," Walsh said. "That's when I realized what an accomplishment, what an historic moment for the city, it was to win a professional championship." The 1984 team was probably Walsh's finest, an 18-1 powerhouse with a record-setting offense and the league's stingiest defense. It pounded Dan Marino and the Miami Dolphins in Super Bowl XIX at Stanford Stadium. That spring (1985), Walsh drafted a receiver from Mississippi Valley State named Jerry Rice, and the offense would get even better. A last-ditch catch by Rice on a pass from Montana stole a victory over the Bengals in 1987. The play was memorable not only because it won the game but because it prompted a bizarre reaction by the head coach: Walsh joyfully skipped off the field. One of the most thrilling Super Bowls (XXIII) followed the 1988 season. Rice was voted the game's Most Valuable Player after making 11 catches for a Super Bowl-record 215 yards. But the 49ers needed a 92-yard drive engineered by Montana in the final minutes and a last-minute, 10-yard TD pass from Montana to John Taylor to beat Cincinnati 20-16. A few minutes later in the locker room, Walsh hugged his son Craig and, to the surprise of others in the raucous celebration, burst into tears. A week later, he revealed why he was so emotional: He had decided he'd had enough earlier that season. He was stepping down. "This is the way most coaches would like to leave the game," he said. Clearly that last year was a strain on Walsh, who was often at odds with DeBartolo and the media. The team struggled to a 6-5 start that year, and Walsh later said his intensity was waning, partly because he was "weary of the daily press-sparring." Ever sensitive to criticism, he said during the playoffs that year, "You become the victim of your success. Everybody expects nothing but wins. They ignore that 27 other franchises have equal desires and opportunities, and that so-called parity gives winning teams tougher schedules and poorer positioning in the draft. "Owners demand high production. Fans get to where they can't understand why you lost, even if the team makes the playoffs before bowing. And the media, they always want to know how you lost, who screwed up, why it wasn't done differently, and every detail about your personal life." He later second-guessed his decision to step down, telling the San Jose Mercury News in 2002, "I never should have left. I'm still disappointed in myself for not continuing. There's no telling how many Super Bowls we might have won." In his decade as the 49ers' coach, Walsh won six division titles and had a 102-63-1 record, a mark made even more striking by the fact his teams won only nine of their first 35 games. There were bitter disappointments during those years. The 1982 team couldn't handle success, suffered from drug problems and went 3-6 in a strike-shortened season. The 1983 team went to the NFC title game, only to lose at Washington 24-21, thanks in part to a couple of debatable calls that set up the winning field goal. Walsh criticized both calls. By the rules, if the officials determine that the pass could not have been caught, even without interference, no penalty is called. Walsh protested that when Wright was called for pass interference, the ball "could not have been caught by a 10-foot Boston Celtic." Before the championship 1988 season, there were three straight years of first-round playoff defeats. Even though the 49ers compiled the NFL's best regular-season record in 1987, their playoff loss caused DeBartolo to strip Walsh of his title of team president. In the ensuing years, Walsh and DeBartolo patched up their differences, and DeBartolo was Walsh's presenter at the Hall of Fame. He was named the "Coach of the '80s" by the selection committee of the Hall of Fame. His impact on the NFL was evident in the number of his assistants who went on to head coaching jobs, including Seifert, Dennis Green, Mike Holmgren, Ray Rhodes, Sam Wyche, Bruce Coslet, Mike White and Paul Hackett. Those coaches in turn spawned a host of other coaches, all imbued with Walsh's distinctive offensive schemes. He was an expert in developing quarterbacks, from Ken Anderson, Virgil Carter and Greg Cook with the Bengals, Dan Fouts with the Chargers, Guy Benjamin and Steve Dils at Stanford and, of course, Montana and Young with the 49ers. He said he looked for resourcefulness, creativity and passing accuracy in his quarterbacks; arm strength was far down the list. "We spent hours on everything a quarterback does: every step he takes, the number of steps he takes, how he moves between pass rushers or to the outside, when he goes to alternate receivers," he wrote in his 1989 book, "Building a Champion" (with former Chronicle columnist Glenn Dickey). "It's similar to a basketball player practicing different situational shots." He told an interviewer that the West Coast offense started with the Cincinnati Bengals, where he was quarterbacks coach and offensive coordinator under coach Paul Brown from 1968-75. Walsh borrowed on the principles of Sid Gillman, the legendary San Diego coach, and others. "It was born of an expansion franchise that just didn't have near the talent to compete," he said. "That was probably the worst-stocked franchise in the history of the NFL. ... The best possible way to compete would be a team that could make as many first downs as possible in a contest and control the football. "We couldn't control the football with the run; teams were just too strong. So it had to be the forward pass, and obviously it had to be a high-percentage, short, controlled passing game. So through a series of formation-changing and timed passes -- using all eligible receivers, especially the fullback -- we were able to put together an offense and develop it over a period of time." The West Coast offense meant the ball could be thrown on any down or distance. It meant having the quarterback get rid of the ball quickly, to limit the risk of sacks or turnovers. It didn't mean ignoring the running game, but it could make up for a weak rushing attack. For example, the 49ers' leading rusher in their first championship year was Ricky Patten, who had just 543 yards. "The old-line NFL people called it a nickel-and-dime offense," Walsh said in his book. "They, in a sense, had disregard and contempt for it, but whenever they played us, they had to deal with it." He pioneered the idea of scripting a game's first 25 plays, a habit he started with the Bengals. At first it was just four plays, then six. When he went to the San Diego Chargers, it was 15, then 25. He refined the script at Stanford, and it later was a staple with the 49ers. The script was never a hard and fast list; he would stray from the list if the situation warranted, then return to it later. "The whole thought behind 'scripting' was that we could make our decisions much more thoroughly and with more definition on Thursday or Friday than during a game, when all the tension, stress and emotion can make it extremely difficult to think clearly," he wrote. Practices under Walsh were not the bruising sessions they were under most other coaches. "We didn't beat guys up," he said in an interview in Football Digest. He preferred to save the contact for the game and concentrate instead on preparing for every situation that might come up in a game. "The format of practice and contingency planning -- those, to me, are the biggest contributions that I've made to the game," he said. Another contribution was the Minority Coaching Fellowship, a program he created in 1987 to help African American coaches improve their job prospects in the NFL and Division I colleges by inviting them to an up-close look at the 49ers' training camps. Among those who took advantage of the program were Tyrone Willingham, former Stanford head coach and current head coach at the University of Washington; Cincinnati Bengals head coach Marvin Lewis and several NFL assistants. The NFL later turned the Fellowship into a league-wide program. When he quit as coach of the 49ers, Walsh moved into a vicepresident's position in the organization. He wasn't there long. He joined NBC Sports in 1989 and teamed with Dick Enberg for three seasons as the network's top analyst on NFL and Notre Dave telecasts. Although Walsh can be very glib, his TV work was cautious, and he didn't seem to enjoy it. Walsh maintained his strong ties with Stanford and, in a decision that surprised the football world, returned as head coach in 1992. He immediately led the Cardinal to a 10-3 record, including a victory over Penn State in the Blockbuster Bowl. "If Walsh was a general," said ESPN analyst Beano Cook, "he would be able to overrun Europe with the army from Sweden." After three years at Stanford and a 17-17-1 record overall, he left coaching for good. "It was time to move on," he said. To him, diagramming plays and getting players to execute them exactly represented an art form. "I am a man who draws pass patterns on his wife's shoulder," he said. He fostered the image of the articulate, white-haired professor who cracked jokes at press conferences and devoured biographies and history books in his spare time. In reality, his cool shell hid a feisty disposition. Fred VonAppen, who coached with him on the 49ers and Stanford, told an interviewer in 1993, "He's a complex man, somewhat of an enigma. I gave up trying to understand him a long time ago. In a way he has the kind of personality that creates a love-hate relationship. He's not always the distinguished, patriarchal guy television viewers are used to seeing on the sidelines. He's a very competitive guy, and he can be scathing, especially in the heat of battle. There have been times when I would have gladly split his skull with an ax. Then again, he's the greatest." Over the years Walsh has served as a consultant in various NFL ventures. In 1994 he helped create the World League of American Football, which became NFL Europe. He returned to the 49ers in 1996 as a consultant, but the organization was in turmoil. DeBartolo was under a federal investigation into his pursuit of a riverboat casino license in Louisiana. Walsh clashed with team president Carmen Policy, personnel director Dwight Clark and some of the coaches. He felt he couldn't get anything done. Meanwhile, salary cap problems were building. He left but came back two years later. Policy and Clark had left for the Cleveland Browns. Walsh helped extricate the team from its cap difficulty and get it through the ownership change from DeBartolo to his sister, Denise York, and her husband, Dr. John York. He had a strong influence in restocking the roster and signed Jeff Garcia, a former San Jose State quarterback then starring in Canada. His faith in Garcia would pay off; the quarterback was elected to the Pro Bowl three times with the 49ers. Walsh turned the general manager's position over to Terry Donahue in 2001, but continued to serve as a consultant. This was a tragic time in his life. His mother died in 2002. A week later his son, Steve, a KGO radio reporter, died of leukemia at the age of 46. His wife, Geri, was still suffering the debilitating effects of a stroke in 1998. He went back to Stanford for a third time in 2004 to work with then-Athletic Director Ted Leland on special projects and fundraising initiatives, as well as serving as a consultant for coaches and athletes. He also was in demand as a public speaker. When Leland left, Walsh served as interim athletic director for seven months and was instrumental in planning for the rebuilding of Stanford Stadium, which was accomplished with breathtaking quickness in 2006. He gave up the athletic director position when Bob Bowlsby took over this year. William Ernest Walsh was born Nov. 30, 1931, the son of a day laborer who worked at various times at an auto factory, a railroad yard and a brickyard. When Walsh was 15, his father got him a job in a garage near the Los Angeles Coliseum. The family moved around California frequently. He had only average athletic skills but was a running back on the football team at Hayward High. Unable to attract a scholarship offer, he played quarterback for two years at the College of San Mateo and went on to an injury-hampered career as a receiver at San Jose State. In college, he met a pretty California woman named Geri Nardini during a day at the beach. Shortly thereafter he proposed, and they married in 1955, the same year he earned his bachelor's degree. After a hitch in the Army at Fort Ord, he became a graduate assistant at San Jose State under his old coach, Bob Bronzan. When Walsh completed his studies for his master's in education in 1959, Bronzan wrote a recommendation for Walsh's placement file: "I predict Bill Walsh will become the outstanding football coach in the United States." He took over a struggling team at Washington Union High School in Fremont -- the team had lost 27 straight games -- and took it to a conference championship in 1957 with a 9-1 season. "When you went to a game, you or one of the guys you worked with had to drive the team to the game," he said. "That was just part of the job, so I learned to drive one of those big school buses." He took a big step forward in 1960 when he was hired as defensive coordinator by Cal coach Marv Levy. In 1963 he moved up to administrative assistant, recruiting coordinator and defensive backfield coach at Stanford under John Ralston. When he left Washington High at 27, he had hoped to be a college head coach by the time he was 30. Instead, he spent the next 18 years as an assistant. In 1966 he took his first pro job with the Raiders and made the switch from defense to offense, coaching the backfield. Although John Rauch was the head coach, Walsh later called owner Al Davis one of his mentors. Another was Paul Brown, who was awarded an expansion franchise in Cincinnati and hired Walsh as quarterbacks and receivers coach for the first Bengals team in 1968. Brown gave Walsh free rein to refine his sophisticated passing game, but when Brown retired in 1976, he named offensive line coach Bill Johnson as his successor. Had Brown named Walsh, it's conceivable that the Bengals, rather than the 49ers, would have been the Team of the '80s. Walsh, who had turned down several promising jobs because he was sure he was Brown's heir apparent, was devastated. Miffed that "nobody would take me seriously," he considered leaving football. "It was beginning to look as if I would never make it as a head coach," he said. Instead, San Diego coach Tommy Prothro hired him as offensive coordinator, and he guided the Chargers' high-powered aerial attack around Fouts. A year later he finally got a head coaching job, at Stanford at the age of 45, and quickly proved he was up to the task of leadership. Two years later, he was the 49ers coach. Three years after that, he was The Genius of San Francisco. He is survived by his wife, Geri, and two children, Craig and Elizabeth. Walsh's coaching history 1956 -- Graduate assistant coach, San Jose State 1957-59 -- Head coach, Washington Union High School, Fremont 1960-62 -- Defensive coordinator, Cal 1963-65 -- Defensive backs coach, Stanford 1966 -- Offensive backs coach, Raiders 1967 -- Head coach, San Jose Apaches (semipro), Continental Football League 1968-75 -- Offensive coordinator, Cincinnati Bengals 1976 -- Offensive coordinator, San Diego Chargers 1977-78 -- Head coach, Stanford 1979-88 -- Head coach, 49ers 1992-94 -- Head coach, Stanford Year by year as a head coach Stanford Year W L 1977 9 3 Won Sun Bowl 1978 8 4 Won Bluebonnet Bow 1992 10 3 Won Blockbuster Bowl 1993 4 7 1994 3 7 (1 tie) Total 34-24 (1 tie) 49ers 1979 2 14 1980 6 10 1981 16 3 Won Super Bowl XVI 1982 3 6 1983 11 7 Lost NFC Championship Game 1984 18 1 Won Super Bowl XIX 1985 10 7 Lost wild-card game 1986 10 6 (1 tie) Lost playoff 1987 13 3 Lost playoff 1988 13 6 Won Super Bowl XXIII Total 102-63 (1 tie) Notes: Won-lost records include postseason games. NFL regular seasons in 1982 and 1987 were shortened to nine and 15 games, respectively, by player strikes. "Funkyslsistah… you ain't funky at all, you just a little ol' prude"!

"It's just my imagination, once again running away with me." | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Very sad. Bill Walsh was a football genius and changed the game forever. I did not know him personally but he seemed like a very nice and humble guy. He turned my favorite NFL team into a powerhouse that was in the hunt for the Super Bowl every year for nearly two decades. He will be missed. "Always blessings, never losses......"

Ya te dije....no manches guey!!!!! "....i can open my-eyes "underwater"..there4 i will NOT drown...." - mzkqueen03 | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Much love and a trip to heaven for a guy who had a personal impact on me deciding to become a football coach. I saw him at a coaching clinic about 5 years ago and asked him a couple of questions about his philosophy. The man is a wizard. His legacy is felt throughout the NFL and College Coaching Family. Guys like Mike Shanahan, Mike Holmgren, Tony Dungy, Dennis Green, Tyrone Willingham, Steve Tedford, Jon Gruden and many more cut their gridiron teeth under the amazing Bill Walsh. We lost a legend. Carpenters bend wood, fletchers bend arrows, wise men fashion themselves.

Don't Talk About It, Be About It! | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Our family has been 49er fans going back to the 60's...one of our favorite coaches, he will definately be very missed. I had the opportunity to meet him briefly when I was about 11 or so b4 they won the 1st superbowl, I met Joe Montana at the same time.

Rest in Peace Mr. Walsh...U were a great coach and a great man  [Edited 7/30/07 13:43pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

karmatornado said: Much love and a trip to heaven for a guy who had a personal impact on me deciding to become a football coach. I saw him at a coaching clinic about 5 years ago and asked him a couple of questions about his philosophy. The man is a wizard. His legacy is felt throughout the NFL and College Coaching Family. Guys like Mike Shanahan, Mike Holmgren, Tony Dungy, Dennis Green, Tyrone Willingham, Steve Tedford, Jon Gruden and many more cut their gridiron teeth under the amazing Bill Walsh. We lost a legend.

Walsh, Gibbs & Parcells - best coaches of their era. | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Here is a nice article about Bill Walsh from long time Bay Area Sports Writer Ira Miller.

http://msn.foxsports.com/...ry/7074920 Walsh's influence on league still felt Ira Miller Sports Xchange, Updated 52 minutes ago Hall of Fame coach Bill Walsh, architect of the San Francisco 49ers dynasty and the popular West Coast offense, died today at 75 after a lengthy battle with leukemia. Walsh was 102-63-1 in 10 seasons with the 49ers, including 10-4 in the postseason. But his impact on pro football went well beyond the 49ers and that prolific offense. Just a couple of months ago, Walsh was enjoying a sandwich and white wine on the patio behind his home, lunching with two sportswriters he has known for many years. Walsh's meal was interrupted repeatedly, because his cell phone rang constantly. There were coaches looking for job recommendations, former players, friends, golfing partners or associates from Stanford University, where Walsh worked in recent years. Even in his twilight years, news of his fight with leukemia no longer a secret, Walsh remained a kingmaker. Nearly 20 years after he coached his final game for the San Francisco 49ers, his influence in the NFL remains strong. In fact, over the last three decades, including the final quarter of the 20th century, it is quite likely there was not a more significant figure in pro football than Walsh. His fingerprints are all over today's NFL. Perhaps his West Coast offense has waned in influence in recent years, but at least a version of it can be found in just about every team's playbook, and the organizational structure that he created with the 49ers remains the model for most teams in the league. Walsh's training camp and practice regimen, which emphasized classroom work and lighter drills than was normal for teams at the time, is now standard practice around the NFL. And it's not stretching a point to say the last Super Bowl, which featured the first two African American coaches ever to reach that game, also was a tribute to Walsh's forward thinking; he was years ahead of the league in recognizing and promoting minority coaches. Before there was a single black head coach in the NFL, Walsh created a minority fellowship program that brought black coaches to training camps to speed their development. Cincinnati coach Marvin Lewis was one of the first to go through the program. Tony Dungy, coach of the reigning champion Indianapolis Colts, once played for Walsh in San Francisco. Walsh, who was voted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1993, coached for only 10 years in the NFL, taking over a down-at-the-heels franchise and transforming it into the team of the decade, if not its own era. But even after he left the 49ers, following his third Super Bowl victory at the end of the 1988 season, he never was far away from the league. Former commissioner Paul Tagliabue called on Walsh for several projects, many involving minority coaches and executives. And the 49ers, whenever they had a problem, called on Walsh, too. He turned the team down once and returned two other times, first as a special assistant to the coaching staff for a year in 1996 and later as club president in 1999 following the departure of Carmen Policy to the expansion Cleveland Browns. There was also a brief turn in broadcasting at NBC and a second run as head coach at Stanford where, more recently, Walsh was the acting athletic director. As a head coach, Walsh's strengths were his offensive ingenuity and his foresight. He was a master coach and strategist, but many in the league thought him even better at personnel judgment. Ernie Accorsi, a general manager with three NFL teams and recently retired from the New York Giants, once observed that Walsh would have been a great general manager even if he never coached a single game. In 1979, Walsh took over a 49ers franchise that was depleted of draft choices following a massive and foolish trade for O.J. Simpson and he built it into a Super Bowl winner in three years. Then he was continually able to re-stock during an era when the draft was the only significant method of adding players. He developed Joe Montana, a third-round draft choice, into a Hall of Fame quarterback. That came after he helped develop quarterbacks Ken Anderson and Dan Fouts as an assistant coach with Cincinnati and San Diego. An even stronger sign of Walsh's vision was his work with Steve Young, also a Hall of Fame-quarterback. Hardly anyone in the NFL thought Young would be a capable quarterback in the league, except Walsh. He traded with Tampa Bay for Young and, of course, eventually was proven correct. Young, of course, is in the Hall of Fame along with Walsh, Montana and Fouts. In 1985, with the 49ers drafting last after winning their second Super Bowl, Walsh traded the final pick of the first round and two later choices to the New England Patriots to move up to the middle of the round. There, he drafted a wide receiver deemed too slow by many scouts. Jerry Rice, of course, developed into arguably the greatest player in NFL history. A year later, going into the draft without a first-round pick, Walsh made a half-dozen draft-day trades that gave the 49ers additional choices. Then he used them wisely, drafting eight players who ultimately started for San Francisco's Super Bowl-winning teams in 1988-89 and also coming away with an additional first-round pick for 1987. Walsh left a loaded franchise for his successor, George Seifert, to win a Super Bowl in the 1989 season, Seifert's first year as the 49ers' coach. And while many of the key pieces were replaced in subsequent years, the 49ers remained strong until Young suffered a career-ending injury in 1998. His offensive concepts were ahead of their time, essentially replacing a lot of running plays with short passes. This earned Walsh a reputation as a finesse coach but, in fact, he believed in physical football at the right time. At the time he took over the 49ers, the general wisdom in the league held that it was necessary to run to set up the pass. Walsh turned that on its head. He believed in passing to set up the run, to get ahead early and then wear an opponent down with a second-half rushing game. Along with that, he considered the importance of the pass-rushing specialist to be vital, particularly in the fourth quarter to protect a lead. Early in the 1981 season, he traded with San Diego for defensive end Fred Dean, a superlative pass-rusher who was embroiled in a contract dispute with the Chargers. Dean, who made 7.5 sacks in his first three games with San Francisco, proved to be the final piece of the 49er championship team. Walsh ruled the 49ers with a strong hand, but he always encouraged his assistant coaches and personnel department executives to voice strong opinions. Ultimately, he would have the final say, but he wanted to hear everyone's opinions. He also knew how to present a gruff demeanor to outsiders when he wanted to deflect the pressure off the players, such as a time during the 1981 season, San Francisco's first championship year, when he went on a tirade because ABC, which then televised Monday night games, failed to include the surprising 49ers among their highlights package. Better known was Walsh's sense of humor. He was a regular presence in the locker room, around the players, and he knew when they needed to be kept loose. One well-known story occurred when the 49ers arrived in Detroit for their first Super Bowl appearance; Walsh, who had flown ahead of the team to attend an awards banquet, borrowed a uniform from a bellman and met the team at the hotel. He disguised himself so well that he actually got into a tug of war with Montana, who did not want to yield his briefcase. A week later, when the team's bus to the Super Bowl was trapped by traffic on a snowy road, Walsh managed to keep his players loose by cracking jokes while they fretted frantically over when they'd arrive at the Silverdome. They got there late, as it turned out, but ready. Walsh didn't just keep his eye on the field or the sidelines. He helped set up a program at the Stanford University business school to train budding football executives and he authored, with Baltimore Ravens coach Brian Billick, a lengthy tome that in essence is a primer on how to put an organization together. Billick, a 49ers draft choice who actually got his start with the team as a public relations assistant, is just one of a large group of NFL head coaches who worked under Walsh. This group includes Super Bowl winners Seifert and Mike Holmgren, whose first NFL job was as Walsh's quarterbacks coach. Sam Wyche, who coached Cincinnati to its last AFC title in 1988 and its last winning season before Lewis, also coached under Walsh. Dennis Green, Ray Rhodes and Bruce Coslet were also among future head coaches on Walsh's San Francisco staffs. Mike Shanahan, Jon Gruden, Jeff Fisher, Pete Carroll, Jim Mora Jr. and Gary Kubiak all were San Francisco assistant coaches under one of Walsh's successors before going to success elsewhere. Although he chose football, Walsh would have been an intriguing personality no matter what he did. He was always fascinating, a master of surprise who managed the neat trick of keeping his distance while keeping close. He could be, alternately, thin-skinned and self-deprecating. He usually managed to turn press conferences around so he could discuss whatever he wanted to discuss. He was a master of creative tension and even occasionally, invented phony enemies for his team. Once, during the 1981 season, Walsh posted billboards around the locker room with quotes, negative of course, allegedly from coach Sam Rutigliano of Cleveland, that week's opponent. The quotes were made up but were designed to aggravate the 49ers. The tactic backfired; the 49ers lost that week. But it turned out to be their only loss of an 18-1 championship season. Other Walsh targets included the so-called "New York media elite", in fact, the media in general. He loved to start a sentence with something like, "Everyone said we couldn't do this," or some such phrase. Yet there was also a raging insecurity about Walsh, perhaps justified because Eddie DeBartolo, the 49ers owner, was such a mercurial figure. Walsh sometimes was not sure people recognized him. Once, at Pebble Beach, he introduced himself to Jack Nicklaus by saying, "Hi, I'm Bill Walsh. Of course, Nicklaus, a big football fan, knew exactly who was Walsh was. Eventually, everybody did. Ira Miller is an award-winning sportswriter who has covered the National Football League for three decades and is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee. He is the national columnist for The Sports Xchange. "Always blessings, never losses......"

Ya te dije....no manches guey!!!!! "....i can open my-eyes "underwater"..there4 i will NOT drown...." - mzkqueen03 | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

http://www.sfgate.com to post comments and to read more stories

http://www.knbr.com to listen to Bay Area sports talk radio. Former football players and colleagues have been sharing their memories. "Funkyslsistah… you ain't funky at all, you just a little ol' prude"!

"It's just my imagination, once again running away with me." | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

| |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Bill Walsh. A NFL legend. a leader who touched a lot of lives.  As a fan of the NFL, and of the Seattle Seahawks. Remember, Bill Walsh. As a fan of the NFL, and of the Seattle Seahawks. Remember, Bill Walsh.  Seattle Seahawks Staff comments about the passing of Bill Walsh. Seattle Seahawks Staff comments about the passing of Bill Walsh. Head Coach Mike Holmgren

For me personally, he gave me my chance to coach in the NFL. He took a chance on me. I was four years removed from high school and that usually doesn’t work that way. He was hard on me and I was mad at him a fair amount as an assistant coach. Looking back on it now, he was my mentor and then later in the years he became my friend. I said this and I meant it, I always thought; when I was an assistant coach for him and he was working and having us do stuff that he looked at the game differently as a coach, he just looked at how to put everything together and how to do it differently. The minority intern program is in place because of Bill. He had a heart for minority coaches and he wanted to make sure they had a chance. Ty Willingham was our first minority coach in San Francisco years ago, the first year the program was in place. A lot of us worked for him and had a chance to go on and continue to coach in the league. We took a lot of what he did with us. I am glad I had a chance to visit with him recently.” (On Walsh’s philosophy...) “I always said that he was an artist and all the rest of us were blacksmiths pounding the anvil, while he was painting the picture. There is always more than one way to win games but that was how he chose to do it.” Special Projects/Defense Coach Ray Rhodes

“He was very instrumental in my career from day one as a football player. He gave me my opportunity in coaching. I had the chance to play for him for a year and after that year he gave me my opportunity to coach in this league. From day one he molded my career and helped me out tremendously. When you talk about the things he would do for his coaches, not only did he show you the on-the-field part of the game but off-the-field part of the game as far as scouting, dealing with player contracts, just all aspects of football he was willing to share with all of his coaches. For a young coach like myself I can’t say enough things about him. He pushed you, he pushed you to be the best person you could be, the best coach you could be. He always had people setting their goals and their standards high in every phase of what they did in football. He pushed me to the point to where, just like he pushed his players, in reference to be the best player you could be. You want to be the best defensive back coach in the league and you have to strive for that with hard work. You want to have the best group, you want to be known as the best guy coaching that position. He pushed each one of his coaches to the ultimate limit and he stayed on you about it. He was a mentor to me. I can’t say enough good things he did for me and my family.” Assistant Head Coach/Secondary Coach Jim Mora

“He not only had a great influence on the game but he had a great influence on many people in this league, myself being one of them. He will be truly missed by everybody.” Special Teams Coach Bruce DeHaven

“I had the opportunity to work with Coach Walsh for three years while I was in San Francisco when he was our general manager. It was a real honor for me to be associated with him. One of the really fine gentleman in the game. You know how innovative he was for the game but I found him to be a wonderful human being, very caring and just a real gentleman. He will be sorely missed by a lot of people.” Defensive Coordinator John Marshall

“Great, great football coach and football mind. Much, much better human being. He has helped so many young players, so many people in general in his professional lifetime. The world is a better place because of Bill Walsh being in it. I’ve coached against him and I’ve coached with him and he has helped me in my professional life and I couldn’t think more of him. I admire the man and I admire what he stood for and I admire what he did.” Assistant Head Coach/Offensive Coordinator Gil Haskell

“He was an extremely fine coach, very detailed. He had a great eye for talent. You look at his teams and they always talked about offense but Ronnie Lott and those kids on defense were great players. I have nothing but respect for him. Later when I started working with Mike Holmgren, I got to know him and I even respected him more because he was very loyal to the guys that he coached. Quite a man, quite a man. He had a great life and was very successful.” | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

New topic

New topic Printable

Printable