The Marvelettes in 1966 What It Was Like Calling Out Around the World: Motown Turns 50 by Diane Leach [30 January 2009] In the early '80s Detroit, Motown was as unquestionable as air. Who didn't like air? I was born in Detroit and lived there until I was 17 years old. It was like this: We weren’t a city with much to be proud of. Then, as now, we had a corrupt mayor. Then, as now, the auto industry was failing and taking the city’s denizens with it. Most of us—my family included—had a great deal to worry about. But Motown was something everybody could be proud of. In a city divided by race and religion, Motown was a source of near universal agreement. Nobody ever yelled “turn that shit down!” when the Supremes or Little Stevie Wonder (as late as the 1980s, DJs were still calling him “Little") or the Temptations were on the radio. And they often were. Motown was as unquestionable as air. Who didn’t like air? It was like this. One of the Four Tops lived in my neighborhood. I’m not sure which one, only that he drove a black Cadillac sedan with a vanity plate reading “FOUR TOPS”. Whenever my mother saw him, she honked and waved. He would nod back gravely. I attended school with one of the Spinners’ daughters. In fifth grade she was a sullen, angry child whose demeanor rebuffed any questioning about her famous father. I also attended school with Smokey Robinson’s goddaughter. I was good friends with this girl, who was beautiful, smart, and a talented dancer. Her family moved among Detroit’s black elite. Our friendship ended when she transferred to Cass, Detroit’s version of the High School for Performing Arts. My friends down the street attended Mercy High School with Gladys Knight’s niece. It was like this. One day—July 13th, 1984, to be exact—I skipped out on my summer job to see Martha and the Vandellas play a free concert at the Universal Mall. My mother went with me. The Universal Mall was far out on the east side of the city, not a place where Jews or blacks were welcomed. Normally we shopped at Northland, literally ducking bullets. But Martha and the Vandellas were playing the Universal Mall (probably because it was much safer), and we went. I was 16-years-old. I carried my Minolta SLR, which I took everywhere in those days, and shot dozens of photos. Martha and the Vandellas were got up in gold lamé, backed by a horn section, drummer, guitarist, and bassist. I was so close to Ms. Reeves that she smiled into my camera. Several times. In between songs she introduced the Vandellas. One was a social worker; I forget what the other did, something equally useful. They were wonderful: Martha Reeves has a terrific voice. Martha is now on Detroit’s embattled City Council, and I hope she did no wrong. It was like this. I remember the night Marvin Gaye, Sr. shot his son, Marvin, Jr. It happened only miles from my family home, a stupid argument over insurance, and the media interviewed Martha Reeves, who was obviously in shock. Her lips were trembling. “I just can’t believe it,” she repeated. Neither could the rest of us. It was like this. One day we were driving down the John Lodge Expressway when my mother pointed out three tall towers. See those? That’s the Brewster Projects. That’s where Diana Ross is from. Berry Gordy had to teach her to eat with a fork. I don’t know whether Diana Ross could use a fork or not before Berry Gordy made her a star, but I do know about Motown’s “Charm School” and house choreographer Cholly Atkins. Everyone did. It was like knowing about the air, or the big, beautiful, archaic cars we manufactured, driving through that air.

Stevie Wonder in 1970 It was like this. My mother loved Motown. In 1971, stuck at home without a car and three kids under five, she played an endless loop of eight track tapes. The Supremes, Gladys Knight and the Pips (she loathed the Pips, and pitied poor Gladys, who was stuck with them), the Four Tops, the Temptations. When I began school, I had never heard of Mother Goose and knew no nursery rhymes. I could, however, sing all of “Baby Love”, “Where Did Our Love Go”, and “Stop! In the Name of Love”. Anybody questioning my rosy view need only consult the J. Geils Band’s 1976 recording Blow Your Face Out. It was recorded live in Boston and Detroit. In Detroit, the band played a cover of “Where Did Our Love Go” to a drunken, stoned, sellout show full of blue-collar rock ‘n’ roll diehards. They went batshit. One might also consult the countless covers of Motown songs: Peter Frampton singing “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours”, Mick Jagger and David Bowie doing “Dancing in the Streets”, Vanilla Fudge’s “You Keep Me Hanging On”, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s long, long interpretation of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine”, Soft Cell’s (remember them?) whiny version of “Where Did Our Love Go”, Phil Collins’ “You Can’t Hurry Love”. Ad infinitum. It was like this. In 1985 my family moved to California. Nobody was buying those big beautiful American cars any more, giving rise to region-wide unemployment and early fodder for a young idealist named Michael Moore. I did not understand that living in a place possessing its own brand of music was unusual until we arrived in Los Angeles, where people made movies instead. Making movies, for Californians, involved much of same feeling Motown did for Detroiters: a sense of ownership, pride, glamour, perhaps even enjoyment. But California movie glamour was a whole other thing, because it involved more money. Lots more money. This is not to say that Berry Gordy didn’t want to make money: he did. He left Detroit early on. But Motown was more homespun: Martha and the Vandellas, free at the mall. It’s difficult to imagine Chevy Chase doing stand-up in a San Fernando Valley Galleria just for kicks, and if a movie star lives in your neighborhood, chances are your neighborhood is much nicer than the one I grew up in. And movie star offspring do not attend public schools. I say it was like this, past tense, because it’s all gone now. The original Motown Records has morphed and folded and is no longer Gordy’s baby. Diana Ross seems to spend more time getting into trouble than performing, and Michael Jackson has also folded and morphed into something warped and barely recognizable. Florence Ballard is dead. Only one of the original Temptations, Otis Williams, is still alive. Gladys Knight has battled compulsive gambling. Their hometown, our hometown, has collapsed. The music still plays, perhaps, but not on the radio. Certainly not on eight-track tapes. There is something wrenchingly anachronistic about downloading “My Girl” or “My Cherie Amor”. It’s music for riding in the Buick, taking Greenfield down to Eight Mile Road (yes, that Eight Mile), the radio tuned to WLBS. We’re going to Northland, where we’ll scope out deals in Hudson’s basement. We’ll try on the hats, shoes for you, a sweater for me. The store speakers will not pump Muzak, but “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg”. Only we won’t really notice, because who notices air? Only people who aren’t getting enough of it. That’s what it was like. [Edited 1/31/09 20:41pm] [Edited 1/31/09 20:42pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

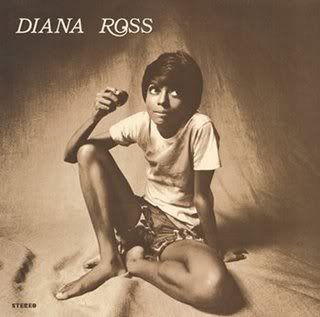

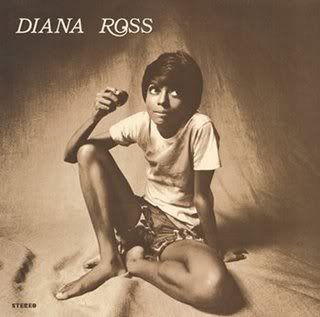

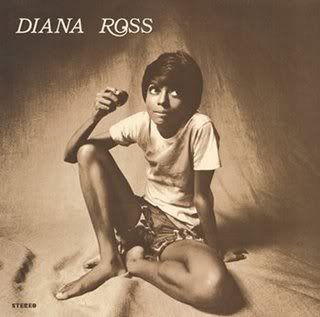

Diana Ross Needles in the Haystack [30 January 2009] by PopMatters Staff

Chris Clark, “If You Should Walk Away” (1967) In this time of celebrating all things Motown, Chris Clark—an accomplished singer, songwriter, photographer, and film executive—remains relatively unsung outside of the label’s completists and Northern Soul enthusiasts. Clark faced a number of hurdles as a recording artist in the mid-to-late ‘60s, and to my knowledge none of them had anything to do with the quality of her musical output. As a white singer on the Motown label, she was met with misgiving by media, fans, and fellow artists. One of the best anecdotes about Clark has her performing at the Fox Theatre in Detroit to a particularly skeptical audience. Berry Gordy’s solution was to have her start singing from off-stage so that those in attendance would admire her voice before being confronted with the color of her skin. It worked, and her whiteness became a non-issue for that crowd. In addition to race politics, label politics are a particularly thorny issue for Motown. Gordy’s selective promotional push for the performers at his music factory certainly had an impact on Clark’s career and that of many others throughout the label’s history. Add to that a backbiting alternative biography of Clark in which she’s a label receptionist and rumors about the effect of her personal relationship with Gordy, and it seems that Clark fought and continues to face an uphill climb towards being acknowledged as a worthy artist. However, to revisit Clark’s 1967 Motown release Soul Sounds is to recognize the versatility of her instrument and the important niche she represents within the sound of young America. The verses on “Born to Love You Baby” flirt with the sounds of bossa nova lounge. “Love’s Gone Bad”, on the other hand, is a stomping blues-rock throw-down that powerfully exorcises the titular bad love and evokes Janis Joplin. Clark’s relatively faithful take on the Beatles’ “Got to Get You into My Life” showcases the interpretive dexterity of her voice as it rivals the punch of the horn arrangement. But there’s no better moment than “If You Should Walk Away”, a Motown ballad written by Gordy and Frank Wilson that was never released as a single. On this number, Clark departs from the speak-singing delivery she uses in many places on the album (most markedly on “I Want to Go Back There Again”, co-written by Clark and Gordy). The opening phrase of “If You Should Walk Away” finds Clark tapping into a smooth section of her range akin to Karen Carpenter’s alto. As the song develops, the oft-cited Dusty Springfield comparison comes into view as Clark adds an edge that fits the song’s narrative about fidelity and strained relationships. This tension and release are also present in the downbeat-driven instrumentation, which breaks occasionally into acoustic guitar and auxiliary percussion interludes. These seem like unnecessary pop gestures that interrupt the sultry sway of the song, but even they bloom into a dynamic, string-enhanced breakdown just past the two-minute mark. Throughout, Clark exhibits her expert control and soulful realization of the material. The sequencing of Soul Sounds somewhat undermines the impact of the song, following it up with the comparatively inconsequential “Whisper You Love Me Boy”. As such, I’ll allow that “If You Should Walk Away” is an excellent candidate for standalone discovery in the mp3 era. This would-be single is an ideal gateway into the many pleasures of Chris Clark and her soul sounds. Thomas Britt

The Mynah Birds, “It’s My Time” (1966) If you and I were chatting about music in a bar and I were to tell you that, at one point, Neil Young and Rick James were in a band together on the Motown label, you would probably walk away thinking I was nuts. But alas, if you dig deep enough into the depths of the legacy of Berry Gordy’s Hitsville USA, you will discover the story of the Mynah Birds, the very first white band signed to Motown. Formed in Toronto, Onatrio in the mid-’60s, the Mynah Birds were primarily a vehicle for the then-teenage James, who went by the name Ricky Matthews, along with a rotating cast of musicians that, at some point or another, included Young on guitar, Bruce Palmer (Young’s future bandmate in Buffalo Springfield) on bass, Goldie McJohn of Steppenwolf on keyboards, and even folk-rock hero Bruce Cockburn. According to Young in an interview with author Jimmy McDonough in Young’s excellent biography Shakey, James at the time aimed to be the black Mick Jagger rather than the funk demigod he grew into during the ‘70s and ‘80s. “Ricky was great,” he stated. “He was a little touchy, dominating—but a good guy. Had a lot of talent. Really want to make it bad… Ricky was the frontman. He’s out there doin’ all that shit and I was back there playin’ a little rhythm, a little lead, groovin’ along with my bro Bruce. We were havin’ a good time. Rick James was really into the Stones. ‘Get Off My Cloud’, ‘Satisfaction’, ‘Can I Get a Witness’, all these songs we used to do. We got more and more into how cool the Stones were. How simple they were and how cool it was.” The Young-Palmer incarnation of the Mynah Birds was the one that got signed to Motown, who funded them studio time where they recorded an album’s worth of material. However, only one proper single, “It’s My Time” b/w “Go on and Cry”, was assigned a catalog number and slated for release. Plans, however, that were shelved after James was arrested for deserting the U.S. Navy, and forced to serve a tour of duty, which, in turn, caused the Mynah Birds to dissolve shortly thereafter. Although there are bootlegs of Mynah Birds material out there on the Internet for savage Neil Young orRick James completists to grab, “It’s My Time” and “Go on and Cry” were eventually released officially on the 2006 box set The Complete Motown Singles, Vol. 6: 1966. Ron Hart

Diana Ross, Baby It’s Me (1977) In 1976, Billboard crowned Diana Ross “Entertainer of the Century”. It was a well-earned coronation. Just six years after leaving the Supremes, Ross had established herself as a formidable talent with a career that spanned records, film, television, and the Broadway stage. Amidst four chart-topping singles, Grammy and Oscar nominations, and a Tony Award for An Evening with Diana Ross, Ross released no less than a dozen albums between 1970 and 1977. Motown ensured that their top-selling female artist remained prolific even as she raised her three young daughters, Rhonda, Tracee, and Chudney. However, Motown’s saturation of Diana Ross product—an average two album per year release schedule—buried some of the singer’s finest recordings. One of those albums, Baby It’s Me was sandwiched between the double live album An Evening with Diana Ross (1977) and Ross (1978), an odds and sods collection of new and previously recorded material. Like many of the albums Ross recorded in the 1970s, it deserves to be rediscovered. Produced by studio wunderkind Richard Perry, Baby It’s Me beckoned listeners to the boudoir. Ross’ come-hither gaze on the album cover was an appropriate preamble to the music. “We wanted to make a record people could make love to,” Perry even disclosed to Ben Fong-Torres in Rolling Stone. Indeed, the songs on Baby It’s Me were ideal for “shadow dancing” in a razzle-dazzle sort of way. Musically, the album contained a pastiche of pristinely orchestrated pop-soul confections. It also marked the full transition from the breathy, ingénue-like quality of Ross’ singing voice to a more mature and stronger tone. Ensconced at Studio 55 in Los Angeles during the summer of 1977, Perry maximized this newfound stridency. “You Got It” symbolizes the particular quality that characterizes the album: Perry’s stylized yet appealing pop and the cut-glass timbre of Ross’ voice. Her exuberant intonation of “got” defines the ecstasy of romantic love, and thus, the theme of Baby It’s Me. The album is a treasure trove of irresistible tracks. “All Night Lover”, a glitzy tribute to the Holland-Dozier-Holland productions Ross recorded with the Supremes, echoes both “Where Did Our Love Go” and “I Hear a Symphony”. Though “All Night Lover” shares much in common with the classic sound of the Supremes, lyrics like “Renew me, do me” distinguish Ross—a sexy, classy woman—from the cooing 20-year old version of herself. “Top of the World” and “Gettin’ Ready for Love”, which was the only single from the album to crack the Top 40 pop charts, were sweeping, buoyant three-minute odes to the stirring sensations of romantic love. The gorgeous “Come in from the Rain” and “Confide in Me”, each co-written by Melissa Manchester, disguised seduction as a seemingly innocuous invitation, while a cover of Stevie Wonder’s “Too Shy to Say” embellished the sweetness of the original with a tinge of melodrama. The title cut is the wild card of the bunch, a track that could only be described as funk-lite burlesque but, nonetheless, bewitching. To simply dismiss the album as “glossy”, which it was upon its release, is to miss out on its numerable charms. (The only truly disposable contrivance is “Your Love Is So Good for Me”, a disco excursion that goes nowhere.) The production might be as slick as Ross’ coif but it’s just as alluring. No one will mistake Ross singing “The Same Love That Made Me Laugh” for Bill Withers, but hearing her navigate the song’s maze of heartache with that distinctive wail of hers summons its own kind of intoxication. During the last 45 seconds of the song, when the 4/4 beat suspends briefly, Ross cries wordlessly against the rhythm section. One can visualize the mascara running down her cheeks, her lipstick still glistening. The moment is executed perfectly under Perry’s direction, of course, but it’s beguiling just the same. While Baby It’s Me vanished from circulation years ago (used CDs fetch upwards of $100), it’s well worth filing through the used album crates to hear how it captures a significant moment in the career of one of Motown’s most legendary artists. Christian John Wikane [Edited 1/31/09 20:43pm] [Edited 1/31/09 20:43pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

What's Going On: Marvin Gaye's Liberation from the Motown Sound [29 January 2009] When Obie Benson of the Four Tops brought him a song he had co-written with Al Cleveland, Marvin Gaye found something that had reflected the way he had been feeling ever since Tammi Terrell's death -- anger, sadness, and disillusionment about his friend's death and the chaotic world around him. by Charles Moss Berry Gordy, Jr., head of the Motown Record Corporation, ran a tight ship. As much as the music was the soul of the business, the business was the soul of the music. From 1961 to 1971, Motown had 110 Top Ten hits. Artists such as Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Stevie Wonder, the Jackson Five, and the Supremes contributed to the label’s success. It was Marvin Gaye, though, who had become Motown’s number-one male recording artist in the 1960s. Motown’s success was built upon a certain musical foundation. “The Motown Sound”, as it was officially called and trademarked, was a brand of soul music with a distinctive pop music influence. It included several signature elements ranging from prominent electric basslines to the use of various orchestral sections and a gospel-style singing treatment with a lead and back-up singers. As much as Gaye had helped develop and popularize this sound, he began to feel stagnant in his musical role at Motown. By the late ‘60s, Gordy’s assembly line-like production took a toll on the artist. Though he had recorded plenty of duets throughout the decade with other leading female artists at Motown (Mary Wells and Kim Weston, most notably), it was his work with Tammi Terrell that proved to be the most powerful. Songs like “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”, “Your Precious Love”, and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” defined the famous duo’s relationship; at least, that was the rumor. When Terrell collapsed into Gaye’s arms during a concert in 1967, it was the beginning of a three-year bout with a brain tumor, resulting in her death in 1970. Gaye had watched his friend slowly wither away. When she died, it sent him spiraling into a deep depression. He refused to record or perform and spent most of the time alone, confined to his home. Terrell’s death, however, would become something of a catalyst for Gaye’s artistic reinvention. Through television news broadcasts, Gaye saw the racial, political, and social problems that were plaguing the world, manifestations from the explosion of political and social activism that took place during the late ‘60s. As he wallowed in his seclusion, Gaye read letters from his brother Frankie serving in the Vietnam War. They described the confusion and frustration he and other soldiers felt fighting in a war that had no just cause. Many black soldiers at the time felt doubly conflicted, drafted to fight and die for a country that refused to accept them because of the color of their skin. These observations, along with the loss of Terrell, motivated Gaye to question his role in the world and at Motown. Gordy set a high standard for his musicians and singers at Motown and was strict about quality control. For those artists who desired a bigger role within the music recording process, this meant limited creativity beyond the prescribed Motown Sound. Gaye, on the other hand, had an ever-growing desire to fully produce his music. Though he often collaborated with his producers and other musicians, offering suggestions on how to improve the songs, he yearned for the creative control that the role of producer would entitle him. When Obie Benson of the Four Tops brought Gaye a song he had co-written with Al Cleveland, a songwriter at Motown, he found something that had reflected the way he had been feeling ever since Terrell’s death—anger, sadness, and disillusionment about his friend’s death and the chaotic world around him. After Gaye read the lyrics to “What’s Going On”, Benson urged Gaye to record the song himself. Upon agreement, Gaye collaborated with the two songwriters and eventually took complete creative control of the song’s production. “What’s Going On” was recorded in Motown’s Studio A on June 1, 1970. Gaye enlisted Motown’s now-famous studio musicians, the Funk Brothers, to record his altered version of Benson’s song. But instead of hanging back in the control room, as most producers do, Gaye intermingled with the musicians, playing piano and creating new sounds. He brought in Chet Forest, who was known for his experience in the realm of the big band genre, to assist with the musical arrangement, as well as an assortment of percussionists playing everything from conga to woodblocks. Gaye even beat on a cardboard box with a pair of drumsticks to create a more hollow percussion sound. The result was unlike anything else in the Motown catalog.

Gordy refused to release it. Claiming the song was too political and too weird to be released as a Motown single, he was convinced the song would never become a hit. After all, it didn’t fit into the Motown Sound formula. Gaye, in response, refused to record any more songs for Motown until the company released it as a single. Eventually, Gordy gave in and the song “What’s Going On” was released in January 1971. The finished product was a mix of Gaye’s intuitive genius, sheer stubbornness, and happy accidents. The first was the accidental recording of an alto sax warm-up. It happened to be just the sound Gaye was looking for as the song’s introduction. The second was the accidental mono playback of a two-track tape, each with a different vocal recording. The two tracks were played at the same time instead of separately for comparison purposes as Gaye had originally requested. Gaye liked what he heard so much that he used this technique as a trademark of his music. Instead of the usual three back-up singers Motown often required, Gaye enlisted a background chorus to support his own soul-dripping voice as he walked around the studio, mike in hand, taking in as much of the magic in the room as he could. When it was released, the single quickly rose to the top of the charts. Gordy immediately called on Gaye for an accompanying album. Though Gaye had an idea of what he wanted for the rest of the album, he wasn’t anywhere near finished writing the remaining songs for it. With the help of Benson, Cleveland, and a few other Motown songwriters, Gaye finished writing the other eight songs, enough for a complete album. After the initial recording, arranger David Van DePitte helped Gaye take the separate pieces of voice, instruments, and studio effects and compile them into a consistent and revolutionary album full of beauty and concept. The songs of What’s Going On are told from the point of view of a black soldier returning home from fighting in a white man’s war. It is an unrecognizable America, filled with racial violence and uprisings, political strife and protests. The album is a question-inducing commentary about change, love, and hate. As songs such as “Save the Children”, “Flyin’ High (In the Friendly Sky)”, and “What’s Happening, Brother” seamlessly flow together as one musical journey, they describe much more than falling in love, hanging on to love or losing love. In fact, many of them aren’t about love at all, at least not the romantic kind of love that Gaye had so often sung about in Motown’s earlier days. The songs on this album describe a realistically bleak world in which death and violence occurs but where hope hangs on—but just barely. The album begs the question, “Who really cares?” It was a complete slap in the face to the pre-packaged feel-good vibes of Gordy’s Motown Sound. The cover of the album is a starkly lit close-up of a bearded Gaye wearing a black vinyl raincoat in the rain. His semi-smiling face stares toward the distance; a look of subtle confidence perfectly captures the tone of the album, but even more so, the way Gaye felt while making it. It was a dramatically different piece of cover art for Motown, much different than the superficial poses so characteristic of Motown’s usual material. It was a simple yet powerful image so pure that it exposed the truth in Gaye’s eye, the truth that couldn’t be ignored. Gaye had found himself and had set himself free. The album produced two more hit singles, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” and “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)”. Instead of quickly fading away as Motown albums often did, What’s Going On stayed on the charts for over a year and sold over two million copies by the end of 1972. It was not only the first Motown album to list its session musicians—the Funk Brothers—in the liner notes, but it was also the first Motown album that could not be simply categorized as “soul” or “R&B”. Though later songs such as “Let’s Get It On” and “Sexual Healing” have defined Gaye as a sex-inducing, sultry-dipped crooner for millions of horny men, his album What’s Going On offered a truer definition of Gaye—the musical genius and revolutionary who broke free from the Motown Sound. [Edited 1/31/09 20:44pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

The Miracles Twirling the Dial: My Motown Memories by Bill Gibron Short Ends & Leader Editor [28 January 2009] For those of us in tune with the sounds of the genre-redefining decade, a transistor radio was the seminal social sidekick. We loved listening to that little mono wonder, its tiny shrill speaker sparking a hundred journeys directly into the center of our mind. As a kid growing up in the 1960s, it was the most coveted accessory you could own. No, not a pair of fashionable Foster Grant sunglasses, or a slick chopper-style bicycle with plastic fringe on the handle bars and a leopard print banana seat (guilty as charged). For those of us in tune with the sounds of the genre-redefining decade, a transistor radio was the seminal social sidekick. We loved listening to that little mono wonder, its tiny shrill speaker sparking a hundred journeys directly into the center of our mind. In conjunction with a weekly trip down to Sears to pick up the latest must-own 45s (always stocked per Billboard‘s Top 40) and your parents’ permission to use the massive console stereo—complete with auto tone arm and “continuous play” spindle—a child had endless sonic opportunities to explore. But you had to have that wireless device first. I’ll never forget the joy upon receiving my first one. Growing up in Chicago had its own unusual aural perks—the primary one being the gig-normous mobile hit parade known as WLS. With its ample supply of AM delights, every hour was a refresher course in the latest supersonic song stylings. There was the Beatles followed up by the Mamas and the Papas, a smidgen of the Strawberry Alarm Clock immediately buttressed up against a classic bit of Miss Aretha Franklin. In one hour you literally hear every significant pop culture cut imaginable. While it argued for its place as the vanguard of commercial music, WLS was just like any all powerful media outlet. It set the tone. It determined the buzz. If it loved an artist or particular group, you heard their latest release in endless, almost omnipresent rotation. If they didn’t like you, or failed to get enough audience response to your latest outing, a particular track could disappear faster than a freak flag at a Mayor Daley rally. I was doubly lucky in that my father coached for the Monsters of the Midway themselves, the Chicago Bears. As a result, my household was an unusually racially integrated place, always mindful of what was happening on the city’s South Side. My father loved all aspects of black heritage, especially the food, and I’ll never forget the arguments he had with my mother over the proper way to cook a sweet potato pie (being from the South, she thought she was right...). With lonely players far from home taking up residence in our living room on a weekly basis, there was always diversity at the dinner table. And on one of those fateful visits, a particularly imposing lineman grabbed my trusty transistor, swung the dial directly past the megawatt WLS, and in a single signal conversion, forever changed my view of ‘60s music. Now I was no dummy. I had heard of Motown. Whenever the Supremes or the Four Tops made their way onto Ed Sullivan’s “really big” stage, I would scoot up toward the TV and watch in rapt pop-soul attention. If any other artists from Hitsville USA had a single in the Top 40, my paper sack from Sears would almost always contain their wax. But learning that there was an entire station dedicated to music like this completely blew my little Caucasian kid mind. As we sat there listening to the latest offering from Marvin Gaye or the Temptations, it was like a gap had been bridged in my upbringing. With my trusty felt marker, I placed a recognizable red mark over my new favorite station. That the name escapes my instant recall today is not some heresy on my part. It took a great deal of mental archeology and a trip through Google to remember WLS. Eventually, I discovered the other important call sign: WVON.

Jr. Walker Because of the communal feeling within the team, everybody appeared to respect each other’s taste. In the locker room, it was always a battle between LS and VON, with each side racking up significant wins. During those intense battle royales, each side would literally sing their favorite song to suggest the next turn of the dial. I was personally witness to several Hall of Fame names belting out off-key versions of Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)”, Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ “Nowhere to Hide”, and most memorably, a high-pitch falsetto take on “The Tracks of My Tears”. Oddly enough, the one song that seemed to bring both sides together was the sensational Smokey Robinson and the Miracles number “The Tears of a Clown”. From the opening orchestral swirl to the fantastic backbeat, that particular tune, no matter the station playing it, got everyone up and dancing. As time progressed and AM gave way to FM, my memories of WLS and WVON remained forever linked to the Motor City’s main musical export. Even today, when a classic Motown track comes up on my iPod or a satellite radio channel, I am instantly whisked back to a time when music knew no specific boundaries, when all parties could dance in the street and easily embrace the sounds coming out of a tinny PA style speaker in Soldier’s Field. Sure, it now seems horribly naïve, and knowing what I know today, there were hundreds of underlying issues involving the Bears that I had little or no experience with (they were the first team to integrate their rooming lists, using position, not ethnicity, as a means of making such a determination). But I will never forget the night I met up with the “real” sound of Chicago by way of Detroit. It turned my transistor radio from something I loved into an indispensible part of my life—and Motown has stayed there ever since. [Edited 1/31/09 20:45pm] [Edited 1/31/09 20:45pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Stevie Wonder & the Funk Brothers These Are the Breaks: The Motown Sound's Influence on Hip-Hop Sampling by John Bohannon [28 January 2009] For any influential group in the hip-hop game, specifically in the early 1990s, Motown's stamp of approval and its variety of subsidiaries were undeniably influential. Talking about the art of sampling without including Motown is like talking about soul music without Otis Redding or rock ‘n’ roll without Elvis—it just doesn’t quite complete the puzzle. The house that Berry Gordy built has been integral to the conception of hip-hop, its implementation of sampling, and the growth patterns of a music that advanced the urban streets of New York and slowly but surely took over the streets of the world. While sampling has held its niche in the underground of hip-hop, legal problems have forced it out to the forefront, unless an artist with stature like Kanye West or Q-Tip takes the time to get his samples cleared. For any influential group in the hip-hop game, specifically in the early 1990s, Motown’s stamp of approval and its variety of subsidiaries were undeniably influential. Everyone from alternative groups such as A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul, to critical darlings like Common and the Roots, to mainstreamers like Tupac and Biggie have all had their hands in Hitsville U.S.A. This is partly due to the volume of records Gordy’s empire was pressing by the late ‘60s—enough for every beat digger to get his fair share of obscure breaks. Although said obscure breaks often dominate, some of Motown’s best sellers would go on to provide the foundation for some of the most well known breaks. If it was a big seller the first time around, might as well try it again, right? The originators of mainstream hip-hop, Run DMC, found chops in the Temptations’ classic “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”, while Public Enemy used some of the band’s lesser known cuts, such as “Psychedelic Shack” and “I Can’t Get Next to You”. There are a number of reasons why these prominent hip-hop artists found comfort in the grooves of the Motown sound. For one, Motown always stuck to the K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple, Stupid) philosophy. One of the most important aspects of a legendary break comes from its ability to be used in repetition; if it becomes too complex, then it is less likely to work its way into the mind of its listeners. A strong backbeat begets an optimum break, and Motown had strong backbeats in spades. The Motown Sound always revolved around the backbeat of drummers like William “Benny” Benjamin, Richard “Pistol” Allen, and Uriel Jones to carry everything else forward, and it was typically accented by Jack Ashford’s tambourine and the rhythmic basslines carried by the legendary index finger of James Jamerson. The collective of musicians known as the Funk Brothers forever changed the face of music up until Motown’s move from Detroit to Los Angeles in the early ‘70s. Both throughout their heyday and through the art of sampling, the Funk Brothers’ style of layering several guitar lines atop a syncopated drummer affords their records a sound unlike anyone else’s. When sampling drums, the feel and volume are of utmost importance—this is why John Bonham has always been one of the legendary sampled drummers. Though Benjamin, Allen, and Jones didn’t pound the kit, they played it with a pure finesse that, when syncopated with an overdub of the same break, truly comes to life. For example, the drums on the Four Tops’ classic “Reach Out I’ll Be There” are crisp and at the front of the mix, something that legendary producer Norman Whitfield had a golden ear for. The orchestral arrangements used to elaborate many of the classics on Motown became another backbone in the hip-hop sound. Providing atmospheres to a beat unlike any guitar or bass could ever achieve, the sweet sound of strings layered behind thick beats led an entire new generation of hip-hoppers to different sonic territory. Elements like the string arrangements on Motown records, the horn arrangements that followed James Brown, and the sparseness found in jazz contemporaries such as Miles Davis, Charlie Mingus, and Sonny Rollins helped put hip-hop on a new scale. It allowed the beats to take on a life of their own, creating atmospheres to get lost in behind the lyrics. This may have been what opened up a world of beat records and gave labels like Stones Throw a lifelong supply of influence. It was about getting past drums alone and into a world of atmospheres where the beats no longer needed lyrics to be a creative force. While we could go into a book-long discussion on the quintessential samples used by artists of Motown songs and artists, that could become irrelevant to a certain extent. What’s important to realize is how the aesthetic territory explored by the Funk Brothers, Whitfield, Gordy, and the wonderful recording artists for the beloved Detroit label and its subsidiaries influenced the aesthetic process in the world of sampling. The sonic territory explored in the Motown lab is a cornerstone in the similar territory explored decades later by a new generation of African-American innovators. For one, the late J Dilla, producer of classics by A Tribe Called Quest, the Pharcyde, and countless other underground icons, is a man of Detroit blood and holds the sounds of Motown near and dear to his heart and sound. It may not have been his samples per say, but his aesthetic approach is very similar to that of the Motown Sound. His beats have always been based on the K.I.S.S. method, and his drums always crisp (even when they were raw-sounding drums). Motown will forever stand on its own as a timeless entity in the realm of popular music. For a younger generation, knowing about Gordy’s legacy may not be at the top of one’s priority list. But for a generation of hip-hoppers that have been exposed to the music of Marvin Gaye, the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, et al through a new styling of music suited to their tastes, the sound of the cut-up beat is one that sends them headlong into a world of wax. Through this, they are exposed to a sound unlike any other, a sound that is gracing the radio each and every day and staying relevant through a new medium—one method sustaining another. [Edited 1/31/09 20:46pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Brian Holland and Lamont Dozier in the mid-1960s Manufacturing Motown by Vince Carducci Like the nameplates on the auto industry's productive output, Motown's headline acts were brand identities under which cultural commodities were sold. For kids like me growing up in the 1960s in a working-class suburb of Detroit, the music of Motown was more than just something you tuned into while flipping through the radio dial. It was a source of major civic pride—“The Sound of Young of America” emanating from the Motor City to rule the national airwaves like the muscle cars that reigned on streets like Woodward Avenue, the main drag that bisects the metropolitan area from the foot of the Detroit River downtown up to the city of Pontiac 20 miles to the north. Running through the various hit songs were the distinctive basslines, precise guitar chords, and solid percussion, instrumental and vocal fills that helped to define the Motown sound. Motown Records was literally a hit factory and it operated on the same assembly-line principles that guided the automotive plants where hundreds of thousands Detroiters, black and white, first staked their claim to a piece of the American Dream. Like the nameplates on the auto industry’s productive output, Motown’s headline acts were brand identities under which cultural commodities were sold. Underneath it all from the very beginning was the powerful drive train of a group of studio musicians known as the Funk Brothers, led by pianist Earl Van Dyke and anchored by master bassist James Jamerson. During Motown’s 1960s heyday, they played on more #1 hit singles than Elvis, the Beach Boys, the Rolling Stones, and the Beatles combined. Italian social theorist and legendary jailbird Antonio Gramsci dubbed the regime of modern industrial capitalism “Fordism”, after the systems and policies implemented early in the 20th century by Henry Ford at the company that at least for now still bears his name. The golden age of Fordism was the 1950s and 1960s. It was the period of widespread prosperity in America following what sociologist Daniel Bell termed “The Treaty of Detroit”, the détente between management and workers written into the UAW’s 1950 contract with American automobile manufacturers. And it’s no accident that the evolution of Motown followed the fate of that industry, which has ruled the company town known as Detroit for more than a century. Motown Records founder Barry Gordy, Jr. learned directly from the master. After washing out as the owner of a record store specializing in jazz, in the mid-’50s he briefly worked on the line at the Ford Wayne Assembly Plant. (Still in operation, it’s where the Focus is currently assembled. In Gordy’s day it was dedicated to the much more upscale Lincoln-Mercury sedan.) Besides recognizing the dim prospects of ever doing anything great while functioning as a cog in a gigantic machine designed to harvest every last drop of his labor (along with that of the legions of drones who anonymously toiled their lives away before and after him), Gordy absorbed the two central principles of Fordist production he would apply to great effect at Motown.

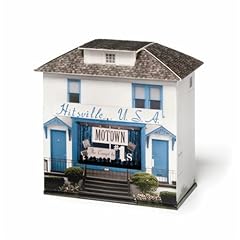

The Funk Brothers in 1966 The first of these is vertical integration, the consolidated management control of all aspects of production. The epitome was the Ford Motor Company Rouge Plant, where raw materials were delivered to the sprawling manufacturing complex, still the world’s largest, processed and spit out the other end as finished automobiles. By the same token, Gordy espoused a business philosophy of “Create, Make, Sell”. Gordy, and soon others on staff, wrote, produced, and recorded songs, published by Motown’s own Jobete Music, in the company studio at Hitsville USA. Motown pressed its own records, designed and printed the jackets and sleeves, and managed all inventory, distribution, and billing. Other Motown units directed product placement, airplay, promotions, and advertising. Another subsidiary, International Talent Management, Inc., handled all of the acts, including booking appearances and directing choreography for all performances, designing costumes, and even providing life-skills training for performer-employees in such things as etiquette, diction, and personal grooming. Motown’s so-called Charm School, where “civilizing” habits were taught, was in essence a knockoff of Ford’s dreaded Sociology Department, which monitored the company’s generally immigrant workforce to ensure “good behavior” in the plant and at home. The “Create, Make, Sell” philosophy also embodied the other core Fordist principle, namely, the division of labor that strictly assigned each employee and operating unit a specific task in the production process. In his autobiography, Temptations lead singer Otis Williams observed: “Artists performed, writers wrote, producers produced.” In the 1960s these lines were rarely crossed, the exception being Smokey Robinson, the only performer to also write his own hit songs and the only one to become a corporate executive. Group names were routinely changed upon signing to make them more marketable (i.e., less R&B “ethnic"). Thus the Primettes became the Supremes and the Matadors the Miracles. The Funk Brothers were often called into the studio to lay down tracks for songs that weren’t finished with lyrics and vocals to be substituted for instrumentals down the line. A separate process, product evaluation, would determine which songs would be released. Another automotive tie-in is that songs would be vetted by playing them through small inexpensive one-way speakers, rather than studio monitors with separate tweeters and woofers, to test for optimum sound reproduction over car and transistor radios, which at the time were primarily tuned to the lower-fidelity AM band. Car companies use different brands to target products for different consumer segments. In the same way, Motown maintained a portfolio of labels to appeal to different listeners. The flagship Motown plus Tamla and Gordy were the labels for crossover records aimed at the mass market. The Soul label was reserved for more “black” R&B product, like one of my favorites, Jr. Walker and the All Stars. (In high school, I played tenor sax in a blue-eyed soul cover band. Among my big moments every gig was to wail on the one-note solo of “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg”.) Black Forum presented spoken word records, typically with inspirational themes of black pride. African jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela’s Chisa Records was affiliated with Motown for a while and he covered the Motown classic, “You Keep Me Hangin’ On”, for his first record, The Reconstruction of Hugh Masekela, released as part of the relationship. Motown even appealed to directly white audiences through Rare Earth Records, featuring extended-jam versions of corporate hits like “I’m Ready” and “(I Know) I’m Losing You” performed by the all-white band after which the label was named.

The Supremes and Holland-Dozier-Holland in 1966 The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the first outsourcing of the American automobile industry with investments in the maquiladoras of Mexico, a transformation in manufacturing often referred to as post-Fordist to distinguish it from the previous production regime. So, too, did Motown begin its exit from the city that gave it its name, a mission accomplished in 1972 when its headquarters officially moved from Detroit to Los Angeles. As with the auto industry, Motown left many workers behind, including the Funk Brothers. Most of the Motown records of this period, including Stevie Wonder’s classics Music of My Mind, Talking Book, and Innervisions, featured freelance studio musicians recording at outsourced facilities in New York or LA (in addition to Wonder’s multi-instrumental talents). The exception was Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, the first Motown record for which the Funk Brothers received liner-note credit and generally considered the greatest soul album ever made. With the onset of digital music in the 1980s, Motown again followed the evolution of global capitalism, in this case in the transition from the industrial to the informational economy. In 1988, Gordy sold Motown for $61 million, though he retained control of Jobete along with all of the publishing rights to its catalog. Like the rest of his fellow media moguls, Gordy’s main business became not making new product but wrenching every last cent of value from intellectual property he already owned. EMI eventually acquired Jobete Publishing, completing the deal in 2004 when it purchased the last 20 percent of the company from Gordy for $80 million. (By that measure the total value of the publishing concern would be $400 million.) The press release announcing the transaction noted that Gordy would stay on to help with “exploitation of the catalog”. Exploiting the catalog has indeed been big business for Motown Records. Not long after the acquisition, the Funk Brothers were called back to active duty to back up pop-star hopefuls who performed selections from the Jobete song roster on American Idol. The top Motown hits have been firmly entrenched in continuous radio rotation since their original release. Reissues have proliferated with “definitive collections” of all the major groups available. The new 50th anniversary multiple-disc set is now on sale, following up on similar 40th, 30th, 25th, 20th, etc., anniversary volumes. There’s an abundance of song placements in movies, ads, and on TV. Ringtone downloads of your favorite Motown tunes can be had from the label’s website. Motown suffered its initial decline in the 1970s with the triumph of the pop-artist auteur and the long-playing album format. But in the age of iTunes and the random shuffle, the catchy hook has returned as a killer app. In this regard, Motown has got legs. That’s more than you can say for America’s auto industry these days. [Edited 1/31/09 20:47pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |

Smokey Robinson in 1963 Danger Heartbreak Dead Ahead by Dave Heaton PopMatters Associate Music Editor If "I've Gotta Dance to Keep from Crying" could work as a slogan for Motown, the song itself works as both a dance song and a tearjerker. If popular music sometimes seems like one continuous song about love, the Motown catalogue can seem especially so. Collectively, Motown’s singers and songwriters captured every side of a love relationship, beginning to end. And even if that subject matter is common in music, the Motown discography, taken as a whole, offers a big-picture view that catalogues life’s excitements and disappointments in specific, visceral ways. To read through a list of Motown song titles is to travel through shades and stages of the heart, from infatuation to love to utter despair, from “Whole Lot of Shakin’ in My Heart (Since I Met You)” to “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)” to “My World Is Empty Without You”. The songs of despair stand out as especially vivid for me. There are numerous classic songs that come to dark conclusions about life: “My Whole World Ended (The Moment You Left Me)”, “My Heart Can’t Take It No More”, “I’ve Lost Everything I’ve Ever Loved”. The Motown labels were full of singers and songwriters that were exceptionally skilled at capturing sadness. My favorite of Motown’s sad songs are those that capture the feeling of desperation in a very specific way, like the Temptations’ “Just My Imagination (Running Away with Me)”, or those that phrase the pain in big, iconic ways, like Jimmy Ruffin’s song that asked the existential question, “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted?” Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ album track “I’ve Gotta Dance to Keep from Crying”, written by Holland-Dozier-Holland, is iconic in a similar way. For me it sums up the whole Motown enterprise, the way we were kept entertained but at the same time reminded of our deep fears and disappointments. It’s a party song, full of party tricks: a litany of dance styles, a get softer/get louder section. It starts with crowd noise and an invitation, “Gather round me swingers and friends / Help me forget my hurt again.” But it’s clear he’s not about to forget. She’s the only girl he ever loved. And she’s gone, forever. If the title could work as a slogan for Motown, the song itself works as both a dance song and a tearjerker. Robinson’s call for the music to get softer is the most touching part for me, his voice carrying more pain than he should be letting show at a party. That’s part of Robinson’s genius, and why he exemplifies for me Motown’s status as great American chroniclers of sadness. The saddest songs, in general, are those about the inner loneliness and heartbreak that no one else knows about: the feelings we keep hidden. Robinson co-wrote and sang several, including two of the greatest: “The Tracks of My Tears” and “The Tears of a Clown”. If the former carries sadness in its sound, the latter takes more of the dancing-to-keep-from-crying route, with giddy music written partly by Stevie Wonder. In both songs, it’s Robinson’s voice that truly breaks the listener’s heart, the way he can capture excitement and regret in the same breath. With its chorus, “The Tears of a Clown” shows some movement towards observational writing, away from a strictly first-person point of view. There may be a similar movement in Motown’s discography. Even when Motown artists sang of social issues, inner sadness still played a key role. Surely “What’s Going On” fits along this same continuum of documenting life’s heartbreaks, even as it looks outside the self, towards the world. [Edited 1/31/09 20:47pm] | |

- E-mail - orgNote -  Report post to moderator Report post to moderator |